Scientists recover the world's oldest RNA in a well-preserved woolly mammoth

For years, the story of the woolly mammoth has felt fixed in the past. Ancient bones, frozen tissue, and fragments of DNA help scientists stitch together how these giants lived and died.

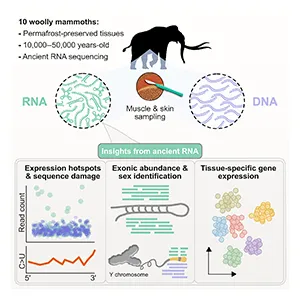

A new study pushes that story even farther. Researchers have obtained RNA from mammoth tissue that spent nearly 40,000 years in Siberian permafrost.

RNA reveals which genes were active when the animal was alive, giving scientists a much closer look at its biology.

Such information has never been recovered from an animal this old. It opens a door that many thought would stay shut forever because RNA breaks down fast. The idea that it could survive thousands of years sounded unlikely.

A team at Stockholm University took on that challenge. Their work shows that RNA can last far longer than expected, and it gives us a new way to learn about extinct species.

Finding mammoth RNA

For a long time, scientists focused on DNA when studying prehistoric animals. DNA is stable and can survive huge stretches of time.

The problem is that it only tells part of the story. RNA reveals which genes were active. That helps researchers see what was happening in the animal’s cells near the end of its life.

The researchers studied tissue from Yuka, a young mammoth whose body was found in remarkable condition.

The permafrost acted like a natural freezer. This gave the team a chance to look for RNA, even though many believed the molecule was too fragile to survive after death.

Pushing back RNA sequencing

The research was led by Emilio Mármol, formerly a postdoctoral researcher at Stockholm University, who is now based at the Globe Institute in Copenhagen.

“With RNA, we can obtain direct evidence of which genes are ‘turned on,’ offering a glimpse into the final moments of life of a mammoth that walked the Earth during the last Ice Age. This is information that cannot be obtained from DNA alone,” explained Mármol.

“We have previously pushed the limits of DNA recovery past a million years. Now, we wanted to explore whether we could expand RNA sequencing further back in time than done in previous studies,” said Love Dalén, a professor of evolutionary genomics.

RNA molecules from a mammoth

The researchers identified patterns of gene activity in Yuka’s muscle tissue. Only some genes were active among the more than 20,000 protein-coding genes in the mammoth genome.

The detected RNA molecules linked to muscle contraction and ways the body manages stress.

“We found signs of cell stress, which is perhaps not surprising since previous research suggested that Yuka was attacked by cave lions shortly before his death,” Mármol said.

Exciting genetic discoveries

The team also found RNA molecules that help regulate genes. Study co-author Marc Friedländer described their importance.

“RNAs that do not encode for proteins, such as microRNAs, were among the most exciting findings we got,” said Friedländer.

“The muscle-specific microRNAs we found in mammoth tissues are direct evidence of gene regulation happening in real time in ancient times. It is the first time something like this has been achieved.”

Study co-author Bastian Fromm is an associate professor at the Arctic University Museum of Norway (UiT).

“We found rare mutations in certain microRNAs that provided a smoking-gun demonstration of their mammoth origin,” noted Fromm.

“We even detected novel genes solely based on RNA evidence, something never before attempted in such ancient remains.”

Studying genes in extinct animals

“Our results demonstrate that RNA molecules can survive much longer than previously thought,” said Dalén.

“This means that we will not only be able to study which genes are ‘turned on’ in different extinct animals, but it will also be possible to sequence RNA viruses, such as influenza and coronaviruses, preserved in Ice Age remains.”

The team hopes to combine this new source of data with DNA, proteins, and other preserved material from prehistoric animals.

“Such studies could fundamentally reshape our understanding of extinct megafauna as well as other species, revealing the many hidden layers of biology that have remained frozen in time until now,” Mármol said.

Lessons from mammoth RNA

Woolly mammoths lived across the cold grasslands of Eurasia and North America during the last Ice Age. They were covered in heavy fur, carried long curved tusks, and lived in large herds.

As the climate warmed, their numbers dropped. The last groups survived on isolated Arctic islands until about 4,000 years ago.

Their story always felt frozen in the past. Now, with the help of ancient RNA, scientists can learn how these animals functioned at a level that once seemed impossible.

The full study was published in the journal Cell.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–