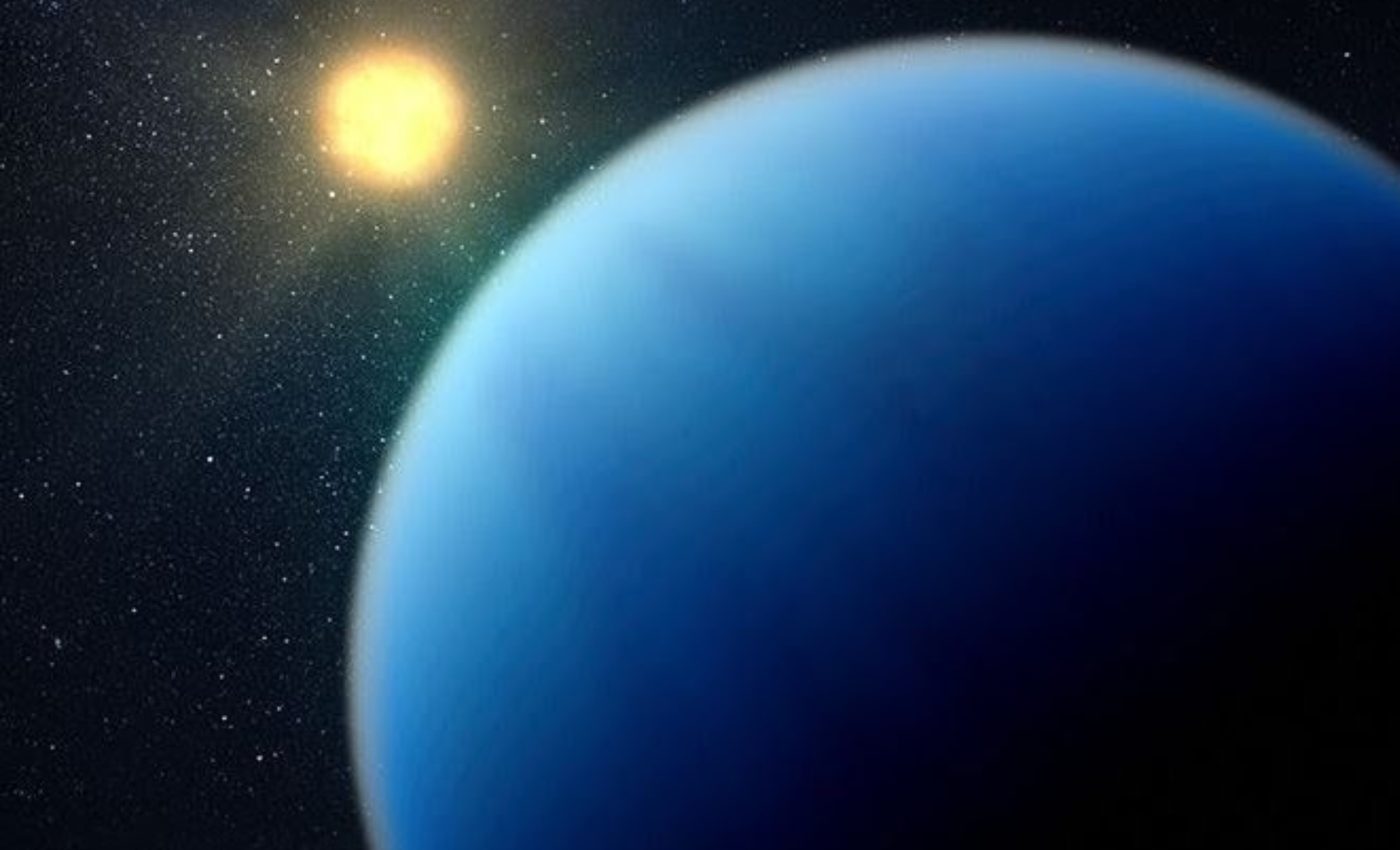

Scorching planets are creating their own water from fire

Some of the hottest known planets look far too scorched to hold water. Yet their atmospheres keep flashing unmistakable chemical hints that water is present – and sometimes abundant.

A new study offers a surprising solution. Deep inside these worlds, molten rock and hydrogen may be reacting to create water outright. In effect, these planets could be forging oceans from within instead of inheriting them from ancient ice.

Led by Harrison Horn of Arizona State University (ASU), the research zeroes in on sub-Neptunes – mid-sized planets larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune that often carry thick, hydrogen atmospheres.

With thousands of confirmed exoplanets in this category, understanding their water supply could reshape how often ocean worlds might exist.

Water’s paradox on hot planets

To tackle that puzzle, the team turned to high-pressure experiments that mimic the deep interiors of hydrogen-rich exoplanets. Classic models say water-rich worlds form far from their stars, where ice condenses, before drifting inward.

For sub-Neptunes that now skim their stars in just a few days, that migration story falls short. It struggles to explain their survival and deep water reserves.

One popular idea had been that icy comets and asteroids bombarded these worlds long ago, delivering deep global stores of water. “There isn’t really a reasonable scenario where that much water is delivered by comets,” said Horn.

Recreating an alien planet in the lab

Horn and colleagues started with tiny pieces of rock chosen to mimic the silicate minerals that make up much of Earth’s interior. They placed these grains inside a diamond anvil cell, a device that squeezes samples between hard tips to reach planetary pressures.

Hydrogen gas then flooded the chamber, surrounding the rock. Lasers heated the sample until it melted into a tiny magma droplet.

At the boundary between molten rock and hydrogen, water molecules formed in amounts that, when scaled up, could match oceans on entire planets.

The experiments showed that hydrogen-rock reactions can create water contents up to a few tens of weight percent in the sample. That production rate is between 10 and 1,000 times higher than simple low-pressure models had predicted.

Oceans born from rock

Inside a sub-Neptune, gravity compresses gas into a deep hydrogen envelope, a thick layer of mostly hydrogen that blankets a rocky core.

That blanket traps heat efficiently enough that the core can stay molten for billions of years. It gives the water-making chemistry time to work. In that molten region, scientists expect a magma ocean, a deep layer of liquid rock that slowly circulates.

Hydrogen can mix into this molten rock, react with oxygen freed from minerals, and create water-rich material that rises into the envelope.

If some of that hydrogen escapes to space while water remains, the planet can evolve from a gas-shrouded world to a denser one. In extreme cases, interior water could form oceans that make up a large share of the planet’s mass.

How sub-Neptunes evolve

Planet formation theories had linked water-rich sub-Neptunes to orbits beyond the snow line, the region of a disk where water freezes into ice.

Horn’s results show that close-in worlds could grow their own water while staying in tight orbits, weakening the link between composition and birthplace.

Observations show that sub-Neptunes are more common than larger Neptunes. They also reveal a divide between compact rocky worlds and those with thicker atmospheres.

Endogenic water production offers a way to read that pattern, where puffier planets may be midway from hydrogen-rich sub-Neptunes to water-dominated worlds.

One outcome is the possibility of hycean worlds – ocean-covered planets with hydrogen-rich air that could host life. The mechanism supplies a route to such planets, turning hydrogen rich envelopes into water layers without requiring that they start as distant icy worlds.

Rethinking ocean planet origins

Not every close-in sub-Neptune will become a gentle ocean planet, because intense starlight can strip away hydrogen and even water over time.

Some worlds may instead end up as superheated steam planets or bare rocky cores, depending on how fierce their host stars are. Where conditions align, this chemistry could produce water for billions of years as fresh magma meets hydrogen.

“They can basically be their own water engines,” said Quentin Williams, a geochemist at the University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC).

Future telescopes that can measure gases in sub-Neptune atmospheres will test whether these worlds carry the thick water layers suggested by the lab work. If they do, then some of the strangest planets we know may also be prime places to search for life-bearing oceans.

The study is published in the journal Nature.

Image Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Dani Player (STScI)

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–