Scorpion-shaped mound may have been an ancient solar observatory

Archaeologists report that a 205-foot scorpion-shaped earthwork in Mexico appears aligned with the summer and winter solstices, according to a new study.

The site sits in the Tehuacán Valley southeast of Mexico City, where farmers once tied the sky to the planting calendar.

Scorpion mound on the valley floor

The work was led by James Neely, a professor emeritus of archaeology at the University of Texas at Austin. His research focuses on irrigation landscapes and community life in the Tehuacán Valley.

The scorpion mound is part of a 12-mound civic and ceremonial group that spans roughly 22 acres and includes rooms and walls.

Only one mound takes a zoomorphic form, making it an effigy mound, a deliberately shaped earthen figure used for ritual or signaling.

Its builders piled dirt and stone into a low body with a head, pincers, and a curling tail that ends in a cluster of ceramics. The feature preserved offerings such as bowls, jars, and a tripod molcajete used for grinding foods.

The builders worked with local stone, including travertine, limestone laid down by mineral springs. That material also caps stretches of nearby canals, signaling tight links between water and ceremony.

Shards and vessel styles date the complex mainly to A.D. 600 to 1100. That span covers Late Classic into Early Postclassic times in central Mexico.

Scorpion mound tracks the sun

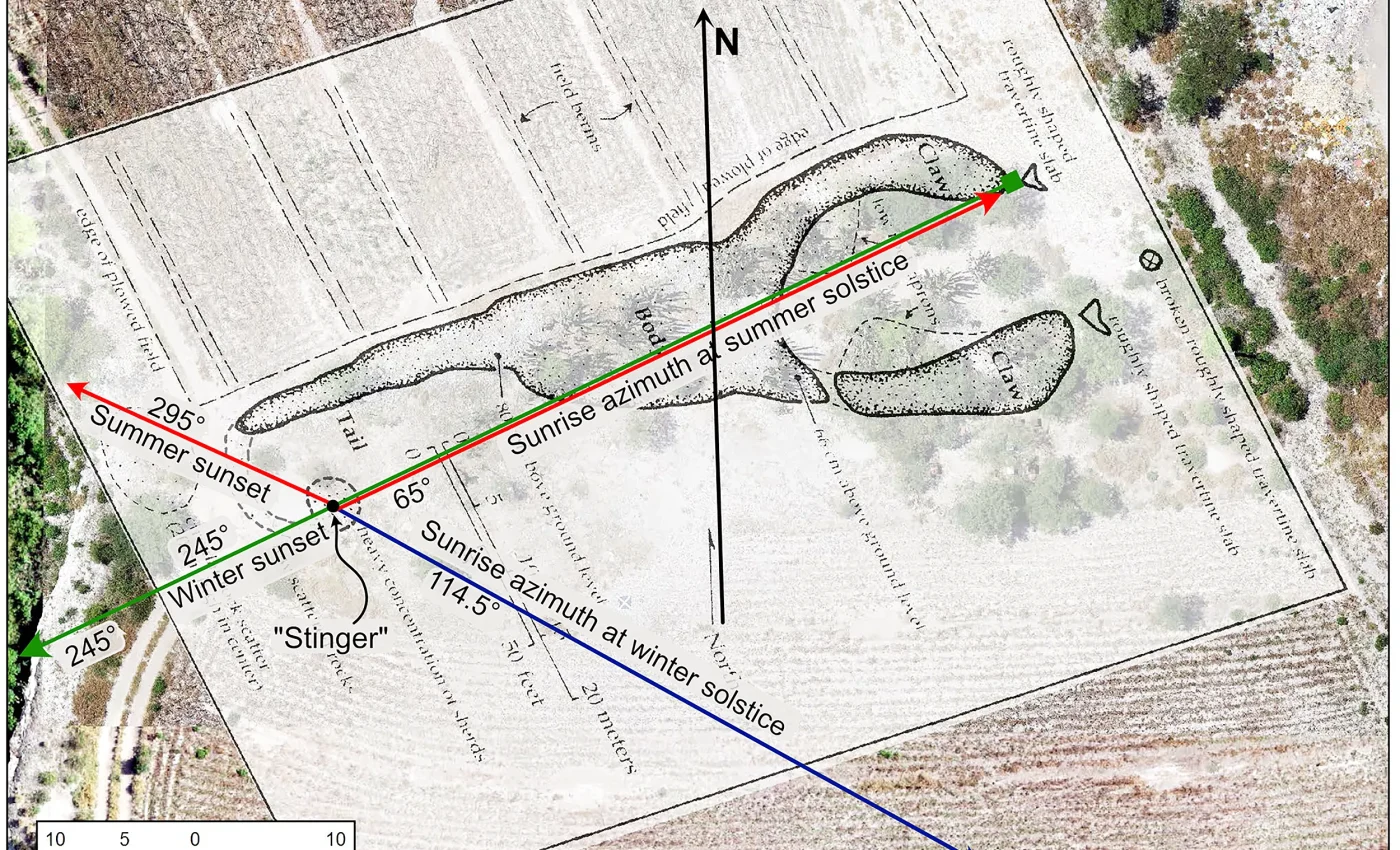

Researchers estimated sunrise and sunset directions using the NOAA solar position calculator. Their modeled lines match the scorpion’s geometry from key viewing spots at the tail and the left claw.

The team focused on azimuth, compass direction in degrees from north. Summer sunrise there sits near 65 degrees, and winter sunset falls near 245 degrees.

“We estimate that on the morning of the summer solstice, if a person sighted from the ‘stinger’ (the circular ceramic cluster at the presumed end of the scorpion’s tail), the sun would rise above the tip of the northern (left) claw,” wrote Neely.

On the winter solstice, a person standing at the tip of the left claw would watch the sun set across the tail’s end. That gives two anchor dates for the agricultural year without metal instruments or written calendars.

The authors stress that mountain horizons and atmospheric refraction can nudge apparent solar positions by fractions of a degree. Field tests with fixed markers would sharpen the picture.

Farming, water, and a sky clock

The mound cluster lies beside fossilized irrigation works that once distributed spring water across broad benchlands. A foundational study documented these travertine-lined canals and their role in intensifying farming in the valley.

In a dry valley with high evaporation, timing is everything. Aligning a monument to the sun’s extremes would help crews prepare fields, plant, and tend crops on schedule.

Ceramics and incense burners from the scorpion mound point to ritual acts tied to water and maize. A visible sky signal could have anchored both ceremony and practical labor.

Placing a shaped mound at the canal junction broadcasts meaning. Water, stone, and sky converge in one built landscape.

Why this matters

Across Mesoamerica, orientations to the sun are common in civic buildings. Certain azimuth groupings reappear with crops and seasonal rites.

Yet animal-shaped earthworks are rare south of the U.S. Midwest. The Tehuacán scorpion stands out as a local community’s take on sky watching rather than a royal capital’s monument.

“This sort of effigy feature is quite unusual in Mesoamerica,” the authors note, underscoring how distinctive this earthwork is in the region. That rarity sharpens its interpretive value.

A researcher shared that the discovery suggests knowledge and control of astronomical phenomena based on solar observations were not entirely limited to the elite class.

More studies planned

Future work could look for postholes or stone pegs at the tail’s ceramic cluster and at the left claw. Such markers would confirm sightlines and reduce ambiguity.

Testing the horizon profile would anchor the numbers. Peaks can shift the apparent sunrise and sunset azimuths by a degree or two.

The team also considered precession, Earth’s slow axial wobble that shifts stellar and solar coordinates over centuries.

Their calculations include small corrections, but field measurements would validate them for local topography.

Excavation could map construction phases, probe artifact clusters, and refine dates. That would show whether the monument was built at once or maintained over generations.

Unraveling the scorpion’s message

The scorpion was a powerful celestial sign in central Mexico, often linked to rain and Venus. The figure’s place in a canal heartland fits a world where agriculture, ceremony, and sky were inseparable.

The mound’s two solstice targets mark the turning points of the sun’s yearly path. Those dates bookend the rainy season that farmers in this valley still watch closely today.

If confirmed, this low, workaday earthwork shows how communities built their own tools for time. Not all astronomy needed a palace.

The study is published in Ancient Mesoamerica.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–