This is what the total collapse of the Earth's magnetic field sounded like 41,000 years ago

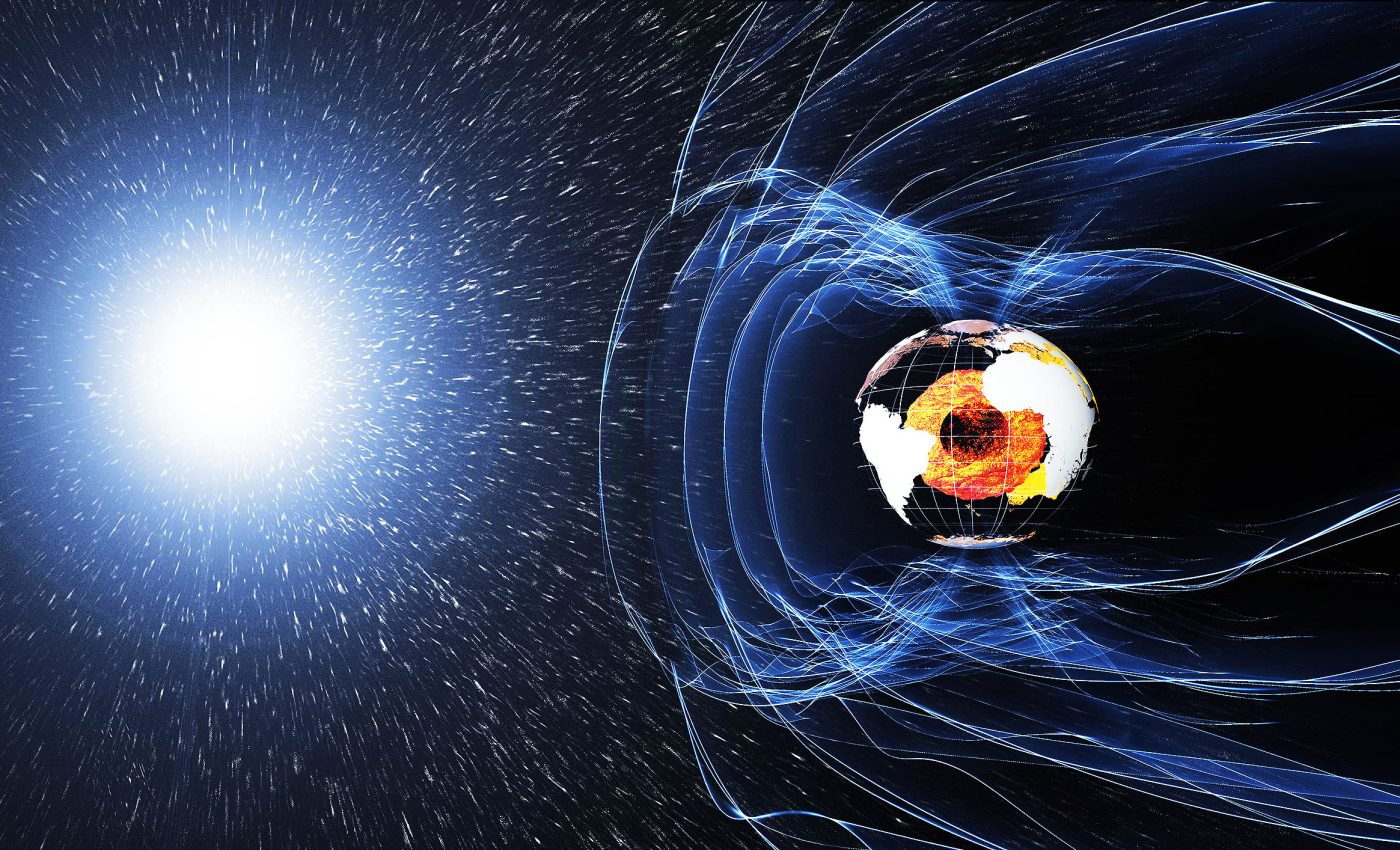

Earth’s magnetic field is not the steadfast guardian that most of us imagine it to be. About 41,000 years ago the field unraveled, then flipped, during the Laschamp event, a geomagnetic reversal that briefly cut its strength to roughly five percent of today’s level

That collapse let torrents of cosmic rays shower the atmosphere, leaving spikes of radiocarbon in ancient kauri trees and beryllium in polar ice.

Klaus Nielsen of the Technical University of Denmark led a team that has now made those silent numbers audible, converting satellite and paleomagnetic data into a two‑minute stereo track that vibrates like subterranean thunder.

Why Earth’s magnetic field flipped

Earth’s magnetic field grows in the molten outer core where liquid iron moves like a planetary dynamo.

When those currents become unstable the dipole tilts, weakens, and can even flip, a process recorded in cooling lava flows on every continent.

Sediment cores show the Laschamp excursion began quickly, perhaps within a single human lifetime, and lingered for about 800 years.

Tree‑ring chronologies reveal the weakest phase lasted a century, with the field hovering near five percent before strength rebuilt.

Cosmic fallout on a fragile planet

With the magnetic curtain tattered, high‑energy particles sliced deeper into the upper air, altering ozone chemistry and shifting wind belts.

Climate proxies from New Zealand to the Andes mark synchronous cooling pulses, and megafaunal extinctions in Australia cluster in the same window.

Modeling of the weakened field suggests surface ultraviolet light may have doubled at mid‑latitudes, bad news for Pleistocene inhabitants who lacked sunscreen but prized red ochre for body paint.

Some researchers link increased auroral activity at lower latitudes to a burst of cave art, arguing night skies turned neon and inspired storytelling.

Sounds of Earth’s magnetic field

Nielsen’s group drew on ESA’s three‑satellite Swarm mission, which has measured Earth’s field with magnetometers since 2013.

Those data, combined with magnetized minerals from ancient sediments, let the team map field lines as they writhed during Laschamp.

Each changing vector was assigned to a loudspeaker in a 32‑channel array buried below Copenhagen’s Solbjerg Square.

Wood creaks, rock falls, and other field recordings were pitch‑shifted and layered to mirror the numerical intensity, producing a low‑frequency growl that migrates from speaker to speaker like a restless tide.

“The rumbling of Earth’s magnetic field is accompanied by a representation of a geomagnetic storm that resulted from a solar flare on Nov. 3, 2011, and indeed it sounds pretty scary,” said Nielsen.

What the audio reveals

The loudest moments coincide with the field’s sharpest dip, emphasizing how vulnerable the planet became.

Listeners notice an almost rhythmic ebb and flow, reflecting brief rebounds when multipolar fragments tried to regain dominance.

A sudden surge near the finale captures the instant the dipole re‑established itself, snapping the poles to their opposite hemispheres.

Researchers say that audible transition helps non‑experts grasp time scales that graphs alone cannot convey.

Public reaction in Copenhagen was visceral; some children hugged parents while older visitors stood transfixed, feeling sub‑bass pulses through their feet.

Nielsen notes that fear was never the aim; the installation intends to remind citizens that the unseen magnetosphere is essential, yet far from permanent.

How the installation came to life

The setup in Copenhagen wasn’t just a technical demonstration, it was an immersive sound sculpture.

Each of the 32 underground speakers represented different spatial segments of Earth’s magnetic field, playing synchronized sounds based on magnetic changes over 100,000 years.

To convert the invisible field lines into sound, the researchers used a technique called data sonification.

Instead of visual graphs, magnetic variations were translated into pitch, volume, and spatial movement, allowing the public to feel the data through vibration and tone.

Why does any of this matter?

Swarm observations show the field has lost about nine percent of its strength over the last two centuries, with the South Atlantic Anomaly expanding westward.

Although most geophysicists caution that a flip is not imminent, the trend underscores the importance of monitoring the ionosphere where many satellites operate.

By sonifying magnetic data, the team offers a fresh outreach tool that bypasses technical jargon and speaks to the body’s instinct for vibration.

Educators are already adapting the soundtrack for classrooms, pairing the audio with aurora videos to illustrate space‑weather hazards.

The Laschamp event also gives climate scientists a natural laboratory for testing models of atmospheric chemistry under extreme radiation.

Understanding that past stress test may refine predictions for how modern infrastructure, from power grids to airline routes, would fare if the shield faltered again.

Human ancestors survived the last collapse with stone tools and campfires; today’s society rides on electronics that could fry in minutes. Turning a page of deep time into sound may be the wake‑up call policymakers need.

Credit for the video and study information goes to the European Space Agency (ESA).

The full study was published in the journal Science.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–