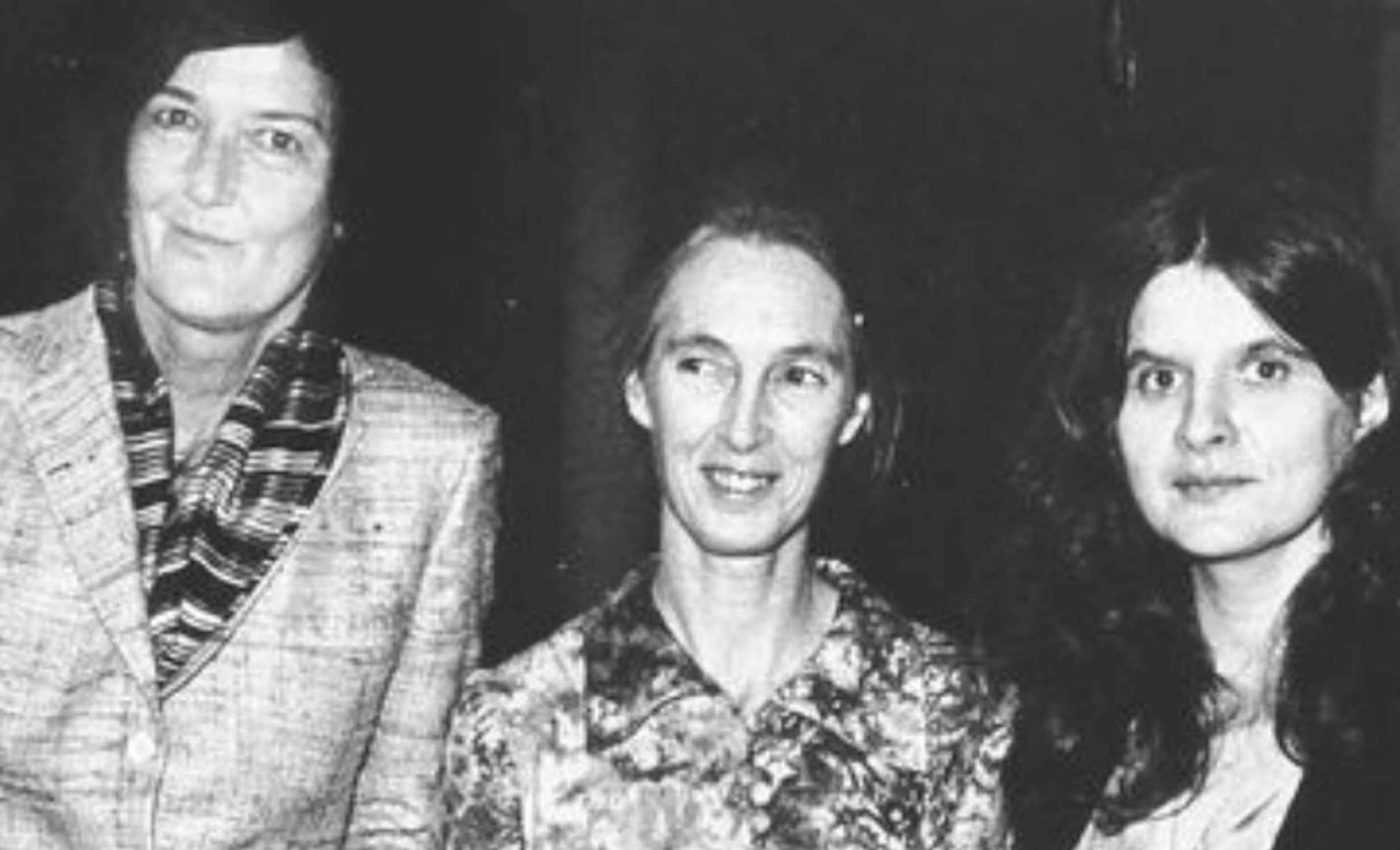

Three women forever changed science and the way we understand primates and ourselves

Jane Goodall’s death in Los Angeles marks the loss of one of the most influential figures in modern animal science.

Her 65-year field study at the Gombe Stream Research Center in Tanzania – now the longest continuous research project on wild chimpanzees – reshaped how the world understands animal behavior, conservation, and the connections between humans and other species.

Her work also formed one pillar of a groundbreaking trio of women whose long-term studies of great apes rewrote the boundaries of biology.

Different level of animal research

Goodall’s research focuses on chimpanzee social life, tool use, and mother-infant bonds. Her patient approach sits within ethology, the study of animal behavior in natural settings. It traded short expeditions for years of close, quiet observation.

Louis Leakey, a paleoanthropologist, backed three early-career women to watch apes in the wild. That plan sent Goodall to chimpanzees, Dian Fossey to gorillas, and Biruté Galdikas to orangutans.

In January 2025, Goodall received the Presidential Medal of Freedom at the White House, where the official citation noted that her discoveries about chimpanzees had challenged longstanding scientific conventions.

Goodall’s research found that wild chimpanzees make and use tools, a finding later published in 1964 in the original paper. That result changed how scientists set the line between human and animal skills.

Her habit of naming individuals pushed researchers to document personalities and relationships. That practice helped reveal alliances, caregiving, and shifting dominance within Gombe communities.

Fossey’s hard fight for gorillas

Fossey worked in the high forests of Rwanda and warned that poaching and habitat loss would erase mountain gorillas.

She built the Karisoke Research Center in 1967 to study and protect them, documenting their family bonds and social hierarchies in detail.

Despite threats from poachers and political instability, she remained steadfast in her animal conservation efforts. She was murdered in 1985 at her Karisoke cabin, a crime widely believed to be linked to her fight against illegal hunting.

Her stance was uncompromising and urgent. Protections that followed helped mountain gorilla numbers recover in the Virunga region.

Galdikas and orangutans

Galdikas showed how slowly orangutans grow and reproduce in Borneo’s peat and dipterocarp forests. She tied their survival to intact forests and the need to curb illegal trade.

Today her centers support research and rehabilitation in Indonesian Borneo. Her long view influenced laws, rescue work, and the debate about tropical forests.

Animal research methods matter

By staying with the same animals year after year, they built a longitudinal record, research that tracks one population across time. That kind of data reveals life histories, alliances, and the costs of conflict.

They also practiced careful habituation – small steps to help animals ignore people nearby. Calm apes made for clearer notes and fewer errors in the field.

Some critics worried about anthropomorphism, the practice of ascribing human traits to animals. The detailed field notes answered with patterns that could be tested and replicated.

Rethinking human behavior

Goodall’s early research forced a rethink across biology and psychology. Many labs widened their view of intelligence, emotion, and culture in nonhuman species.

Fossey broadened who gets counted in social studies, drawing attention to females, infants, and subordinate animals. That shift improved models of primate families and how power actually works.

Galdikas brought orangutans into the center of conservation science. Her persistence kept attention on forests, peat fires, and the slow rebuilding of great ape populations.

Guiding today’s animal conservation

Community partners now anchor the most durable projects. Local rangers, trackers, and health workers shape priorities and share the gains of protected landscapes.

Long-term datasets help forecast disease risks and climate shocks. Plans for corridors and patrols draw on decades of mapped movements and births.

Field studies now blend camera traps with GPS collars when appropriate. The goal is minimal disturbance with maximum clarity on animal choices.

Local communities are not just stakeholders, they are co-authors of conservation. That shared ownership keeps trust and data flowing year-round.

Teaching with animal observation

Observation comes first, then open questions, then tests. A strong field notebook turns small details into insights.

Students can code behavior, graph time budgets, and compare groups. Simple tools, used consistently, teach how evidence grows.

Comparing notes across seasons shows how animal behavior shifts with food. Patterns emerge that challenge assumptions and sharpen future questions.

Animal research lessons learned

Their projects seeded institutions that still run today. The Jane Goodall Institute and the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund train local scientists and carry new research forward.

Roots & Shoots, the youth program Goodall started, helps students link local projects to global goals. Many careers began with small acts, like planting a tree or mapping a creek.

Each woman also changed public expectations. Long term field science now commands respect and steadier support from funders and universities.

These lives suggest a clear lesson for students. Good questions plus patient observation can still move science forward.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–