Two very different pterosaur species discovered sharing an ecosystem

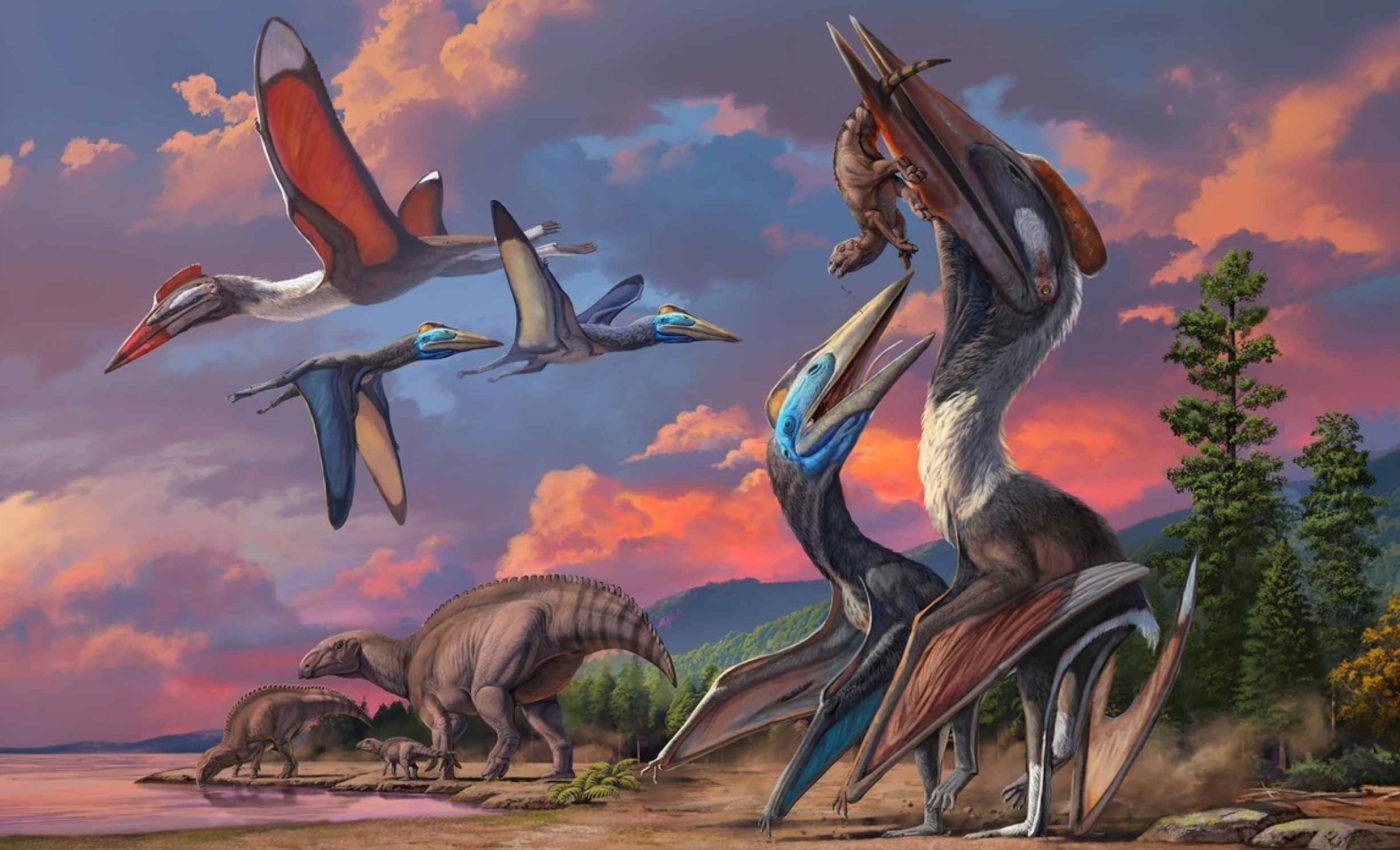

Two newly described pterosaur species from Mongolia’s Gobi Desert are reshaping how scientists picture the Late Cretaceous skies.

Found in the same rock layer, the pair represents strikingly different size classes – one with an estimated wingspan of about 11 feet, the other likely under 6.5 feet.

Both pterosaurs lived roughly 96 to 90 million years ago, yet their coexistence hints at a more finely divided airborne ecosystem than previously recognized.

Pterosaurs in Mongolia shared space

These animals belong to the Azhdarchidae, a toothless pterosaur family with long necks. They were the most widespread pterosaurs near the end of the Cretaceous.

The work was led by Rafael V. Pêgas, a paleontologist at the Museum of Zoology of the University of São Paulo (MZUSP). His research focuses on pterosaur diversity and neck anatomy.

The team named the medium species Gobiazhdarcho tsogtbaatari and the small one Tsogtopteryx mongoliensis.

Naming both from the same formation helps scientists see how size classes shared habitats without tripping over each other.

The pattern matters for ecology, not just labels. Different sizes likely chased different prey and avoided direct competition.

Bones map the pterosaur family

The two fossils are neck bones, or cervical vertebrae, the series of segmented neck elements in vertebrates. In azhdarchids, these bones are long and hollow, which makes them delicate but very informative.

Gobiazhdarcho shows features that place it near a giant-prone branch of the family. This clade, a group that shares a common ancestor, also includes the enormous Quetzalcoatlus and Arambourgiania.

Tsogtopteryx has unique ridges and a keel on its neck vertebra, which flags it as a separate lineage. It sits closer to Hatzegopteryx, a form known for a shorter, stronger neck.

“We argue that Hatzegopteryx had a proportionally short, stocky neck highly resistant to torsion and compression,” wrote Darren Naish and Mark P. Witton, authors of an associated paper.

Small meets giant

Tsogtopteryx is among the smallest named azhdarchids so far. For context, a Canadian specimen from Hornby Island shows a Late Cretaceous azhdarchoid with a wingspan of about five feet.

In contrast, Quetzalcoatlus is recognized as the largest flying creature ever discovered and remains one of the most widely known pterosaurs. Gobiazhdarcho is not a giant itself, but it anchors a branch that produced giants later in time.

Upper Cretaceous pterosaurs are rare in Mongolia, even though dinosaur fossils are common there. The same Gobi localities first yielded pterosaur bones in 2009.

That is why two named pterosaurs from one formation draw so much attention. They add precision to a fossil record that once looked like a blank space.

Rebuilding the ecosystem

Paleontologists think the Bayanshiree Formation once hosted rivers, floodplains, and scattered lakes, creating a mosaic of habitats.

The discovery of these pterosaurs alongside hadrosaurs, turtles, and small mammals suggests a thriving ecosystem that supported both ground-foraging flyers and large herbivores.

The coexistence of Gobiazhdarcho and Tsogtopteryx within that environment hints that size differences may have shaped behavior.

Larger azhdarchids likely stalked open floodplains, while smaller ones could have exploited forest edges and stream margins, feeding on insects, carrion, or small vertebrates.

Insights into azhdarchids

The pair fits a recurring theme. Multiple azhdarchid species with different sizes often show up in one deposit, a sign of fine-grained niche sorting.

The new analysis refines phylogeny, the family tree built from shared features, by placing the medium species near the Quetzalcoatlus line and the small species near the Hatzegopteryx branch. That split hints at two strategies living side by side.

Lessons from Mongolia’s pterosaurs

Size estimates from neck bones carry uncertainty. Neck proportions vary across azhdarchids, so researchers cross-check widths and articular surfaces against better-known skeletons.

There is a safeguard here. The bone texture and fusions in the specimens indicate mature or near-mature individuals, which reduces the risk of mixing juveniles with adults.

Medium and miniature pterosaurs living together show that the Late Cretaceous skies were not ruled only by giants. Small flyers still carved out space among towering contemporaries.

The Gobi Desert now records that split in one place and time. That makes future discoveries there especially valuable.

Scientists will look for skulls, limb bones, and more of the neck to tighten flight and feeding inferences. Better samples can turn cautious size estimates into firmer numbers.

Until then, the new names help connect dots across Asia and beyond. They show how pterosaur life branched, shrank, and scaled up on different tracks.

The study is published in the journal PeerJ.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–