Webb captures the oldest supernova ever discovered

Astronomers just discovered the oldest supernova to date. Named GRB 250314A, this ancient star exploded at a time when the universe was still finding its footing.

Not long after the first galaxies lit up the dark, something massive collapsed, exploded, and sent its light racing across space for billions of years until it finally reached us.

That light didn’t arrive in a neat, simple package. It appeared first as a short, violent burst, then later as a slower, swelling glow.

Put together, those signals allowed scientists to identify the earliest supernova of its kind ever seen, with help from the sharp eyes of NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

Supernova GRB 250314A

NASA says Webb observed a supernova that exploded when the universe was only 730 million years old, making it the earliest detection of its kind to date.

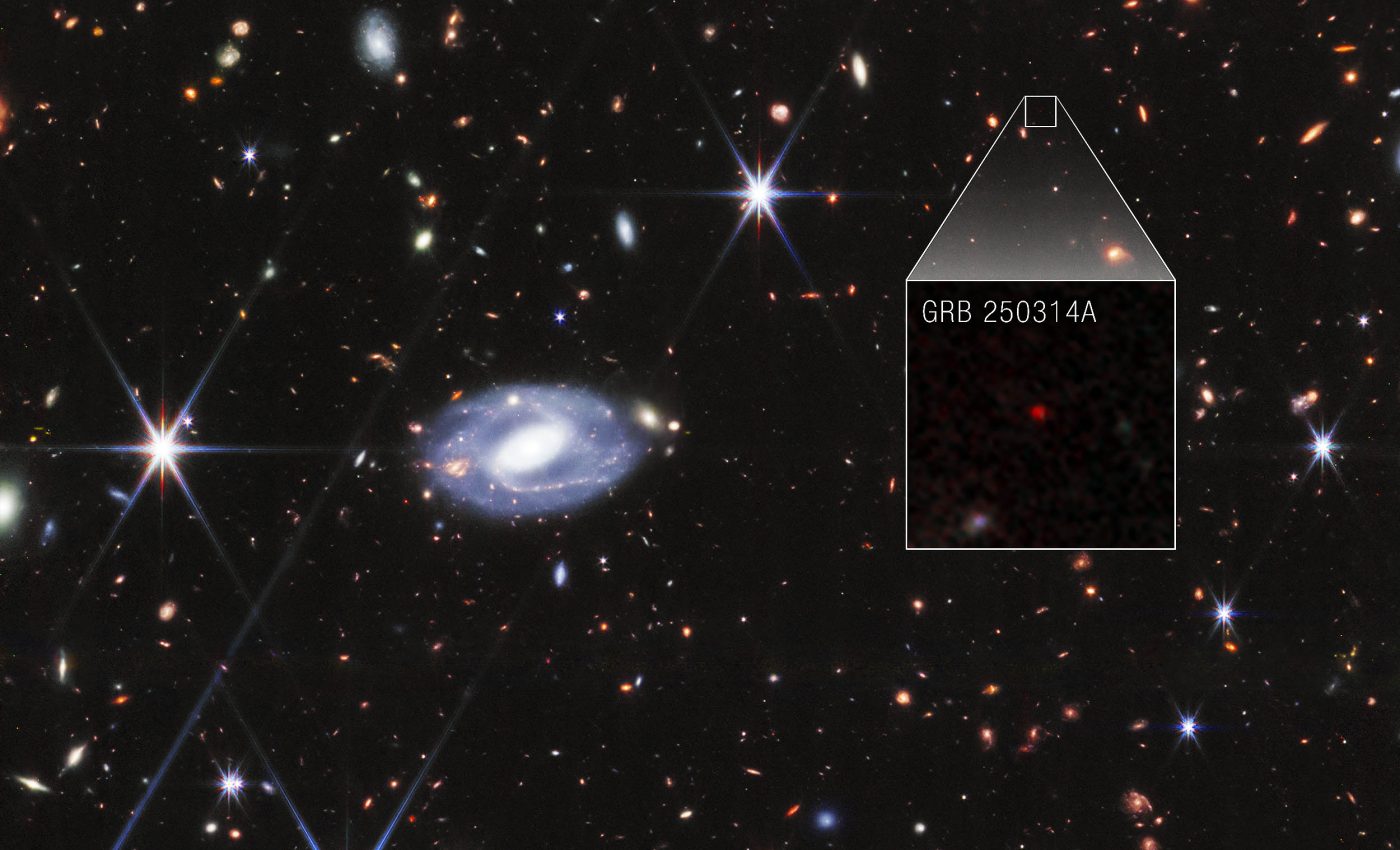

Webb’s near-infrared images were sharp enough to pinpoint the supernova’s faint host galaxy as well.

The telescope made these rapid-turnaround observations on July 1 after an international network of telescopes spotted a powerful flash called a gamma-ray burst in mid-March.

This new detection also surpasses Webb’s own earlier record. Before this, the most distant supernova Webb had directly studied came from a star that exploded when the universe was about 1.8 billion years old.

The researchers didn’t just want to know that something bright happened. They wanted to prove what it was. That’s where Webb’s sensitivity mattered.

Andrew Levan, the lead author of one of two new papers in Astronomy and Astrophysics Letters, is a professor at Radboud University in Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

“Only Webb could directly show that this light is from a supernova – a collapsing massive star,” said Levan. “This observation also demonstrates that we can use Webb to find individual stars when the universe was only five percent of its current age.”

“Webb provided the rapid and sensitive follow-up we needed,” said Benjamin Schneider, a co-author and a postdoctoral researcher at the Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille in France.

Following a powerful cosmic burst

Gamma-ray bursts are some of the most extreme events scientists can catch. Most last seconds to minutes, and they’re rare enough that each one can feel like a once-in-a-career alert.

Short bursts can come from collisions involving neutron stars and black holes. Longer ones, including this event that lasted around 10 seconds, are often tied to the deaths of massive stars.

In this case, the first alert came on March 14. The gamma-ray burst was flagged by the SVOM mission, a Franco-Chinese telescope launched in 2024 to hunt short-lived sky events.

Within about an hour and a half, NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory pinned down the X-ray location in the sky, setting up the next wave of observations.

About 11 hours after the first alert, the Nordic Optical Telescope in the Canary Islands caught an infrared afterglow. Then, four hours later, the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile estimated that the source dated to about 730 million years after the big bang.

“There are only a handful of gamma-ray bursts in the last 50 years that have been detected in the first billion years of the universe,” Levan said. “This particular event is very rare and very exciting.”

Why GRB 250314A took its time

A typical supernova brightens over weeks and fades more slowly after that. This one behaved differently. It brightened over months.

Part of that comes down to distance and cosmic expansion. Light from the early universe gets stretched as space expands, shifting it toward infrared wavelengths. Time gets stretched, too. Events can appear to unfold more slowly than they would nearby.

That’s why Webb’s observations were timed for about three and a half months after the gamma-ray burst ended, when the underlying supernova was expected to be brightest.

This early star looked familiar

You might expect a supernova from so early in cosmic history to look strange. After all, the first billion years were different.

Early stars likely had fewer heavy elements. They may have been more massive and lived shorter lives. This era also overlapped with the Era of Reionization, when gas between galaxies was more effective at blocking high-energy light.

So the team compared what they saw with supernovae closer to home, where astronomers have decades of detailed measurements. The surprise was how normal it seemed.

“We went in with open minds,” said Nial Tanvir, a co-author and a professor at the University of Leicester in the United Kingdom. “And lo and behold, Webb showed that this supernova looks exactly like modern supernovae.”

That doesn’t mean everything is identical. It means the broad shape of the event, the way it brightened and faded, and the clues in its light match patterns astronomers already recognize.

The next step is finding the subtle differences that might reveal what early stars were really like.

Supernova’s home galaxy

Webb didn’t just catch the explosion. It also helped locate the supernova’s home galaxy, which is no small feat when you’re looking back that far. At those distances, galaxies can be so compact and faint that they blur into just a few pixels.

“Webb’s observations indicate that this distant galaxy is similar to other galaxies that existed at the same time,” said Emeric Le Floc’h, a co-author and astronomer at the CEA Paris-Saclay in France.

Right now, what scientists can learn about the galaxy is limited because its light is blended into a tiny smudge. Still, the fact that Webb could see it at all matters.

The observation gives researchers a place to start when they ask bigger questions, such as how fast galaxies grew in the early universe and how their stars lived and died.

Lessons from GRB 250314A

The team used a rapid-turnaround observing program to study supernova GRB 250314A, and they are already planning more.

The idea is to use gamma-ray bursts as signposts: catch the burst, track the afterglow, and let that glow help reveal the galaxy that hosted the event.

“That glow will help Webb see more and give us a ‘fingerprint’ of the galaxy,” Levan said.

In the big picture, this is what modern astronomy is starting to do best: react quickly, coordinate across the world, and grab fleeting signals before they fade.

Webb is built for deep, detailed infrared views, and in this case, it turned a brief flash into a clear story about a star that died when the universe was still young.

The full study was published in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics Letters.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–