Dinosaur extinction completely reshaped Earth’s ecosystems

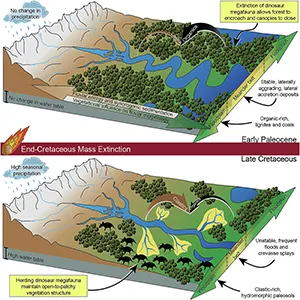

Dinosaurs didn’t just stomp across Earth’s surface – they literally reshaped it. New research has revealed that the dinosaur extinction event 66 million years ago didn’t just change which animals ruled the planet.

It also changed how rivers flowed, how forests grew, and what kinds of rocks now lie beneath our feet.

For a long time, geologists have noticed a strange pattern: the rocks that formed just before dinosaurs disappeared look very different from the rocks that formed just after.

Some experts blamed sea level changes, while others believed it was just coincidence. But the evidence didn’t quite add up.

A team of paleontologists decided to take a closer look, and what they found points to a different explanation: once dinosaurs were gone, forests exploded in size.

That green takeover stabilized the land, narrowed rivers, and left behind very different rock formations.

Rocks reveal ecosystem changes

The study focused on areas in the western United States – including Montana, the Dakotas, and Wyoming – where the rocks hold clear signs of what life was like before and after the dinosaurs vanished.

These aren’t just any rocks. They’re like pages of Earth’s diary, and the team looked closely at a section called the Fort Union Formation.

Before the extinction, the rocks showed signs of soggy, unstable floodplains. Soil wasn’t well-developed, and rivers wandered across the land, spilling out in many directions. But just above the line that marks the end of the dinosaurs, things change.

Suddenly, the rocks are neatly layered, with different colors stacked like stripes on pajamas. Scientists used to think these were pond deposits left by rising seas, but the team discovered they had been misread.

“We realized that the pajama stripes actually weren’t pond deposits at all. They’re point bar deposits, or deposits that form the inside of a big meander in a river,” said Luke Weaver, a paleontologist at the University of Michigan who led the study.

Dinosaur extinction transformed Earth

The changes weren’t just cosmetic. The team found that the rivers had started flooding less often. That’s important because when rivers flood, they carry sand, silt, and clay across the landscape.

If floods are rare, the land stays quiet – and organic material like leaves and wood has a chance to build up. That leads to the formation of lignite, a type of coal, and that’s exactly what the researchers found.

“By stabilizing rivers, you cut off the supply of clay, silt and sand to the far reaches of the floodplain, so you’re mostly accumulating organic debris,” Weaver explained.

The missing piece: A space rock

To be sure these changes happened right after the dinosaurs died out, the team looked for a key clue – the iridium anomaly.

Iridium is rare on Earth, but common in asteroids. When the Chicxulub asteroid hit the Yucatán Peninsula, it spread a thin layer of iridium-rich dust across the globe. That layer marks the moment the dinosaurs disappeared.

In a part of Wyoming called the Bighorn Basin, the researchers tested a thin band of red clay at the point where the geology changed.

“Lo and behold, the iridium anomaly was right at the contact between those two formations, right where the geology changes,” said Weaver.

That sealed the case. The shift in river and forest structure came right after the asteroid hit.

Dinosaurs as ecosystem engineers

The team started asking a bigger question. Could dinosaurs have been shaping the environment more than anyone realized?

During their time on Earth, dinosaurs were massive. Some weighed over 70 tons. They would have trampled vegetation, eaten tons of plant material, and kept forests from growing too thick.

Without them, trees had a chance to spread and form dense forests. These forests helped trap sediment and direct river flow.

“That was the light bulb moment when all of this came together,” Weaver said. “Dinosaurs are huge. They must have had some sort of impact on this vegetation.”

Modern animals like elephants do the same thing. They knock down trees, open up grasslands, and shape their habitats. The idea that dinosaurs did something similar – on a much larger scale – is now gaining traction.

“To me, the most exciting part of our work is evidence that dinosaurs may have had a direct impact on their ecosystems,” said study co-author Courtney Sprain.

“Specifically, the impact of their extinction may not just be observable by the disappearance of their fossils in the rock record, but also by changes in the sediments themselves.”

Dinosaurs reshaped Earth’s ecosystems

The asteroid strike that wiped out the dinosaurs caused instant changes – both in life and in the landscape. That’s worth thinking about today as humans rapidly change the planet, noted Weaver.

“The K-Pg boundary was essentially a geologically instantaneous change to life on Earth, and the changes we’re making to our biota and to our environments more broadly are going to appear just as geologically instantaneous,” Weaver said.

“What’s happening in our lifetimes is the blink of an eye in geologic terms, and so the K-Pg boundary is our best analog to our very abrupt restructuring of biodiversity, landscapes and climate.”

The full study was published in the journal Nature Communications Earth and Environment.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–