Fossils reveal ancient lizard species with four eyes

For the first time, researchers have identified a jawed vertebrate that had four eyes. The discovery that an extinct species of monitor lizard had a third and fourth eye will give scientists new insight into the evolution of eye-like structures located on the top of the head known as pineal and parapineal organs.

The pineal and parapineal organs play important roles in orientation, circadian rhythm, and annual cycles. The researchers explained that the photosensitive pineal organ, which is often referred to as the third eye, is found in many lower vertebrates such as fish.

Krister Smith at the Senckenberg Research Institute in Germany is one of the study’s co-authors.

“On the one hand, there was this idea that the third eye was simply reduced independently in many different vertebrate groups such as mammals and birds and is retained only in lizards among fully land-dwelling vertebrates,” said Smith.

“On the other hand, there was this idea that the lizard third eye developed from a different organ, called the parapineal, which is well developed in lampreys. These two ideas didn’t really cohere.”

“By discovering a four-eyed lizard–in which both pineal and parapineal organs formed an eye on the top of the head–we could confirm that the lizard third eye really is different from the third eye of other jawed vertebrates,” Smith explained.

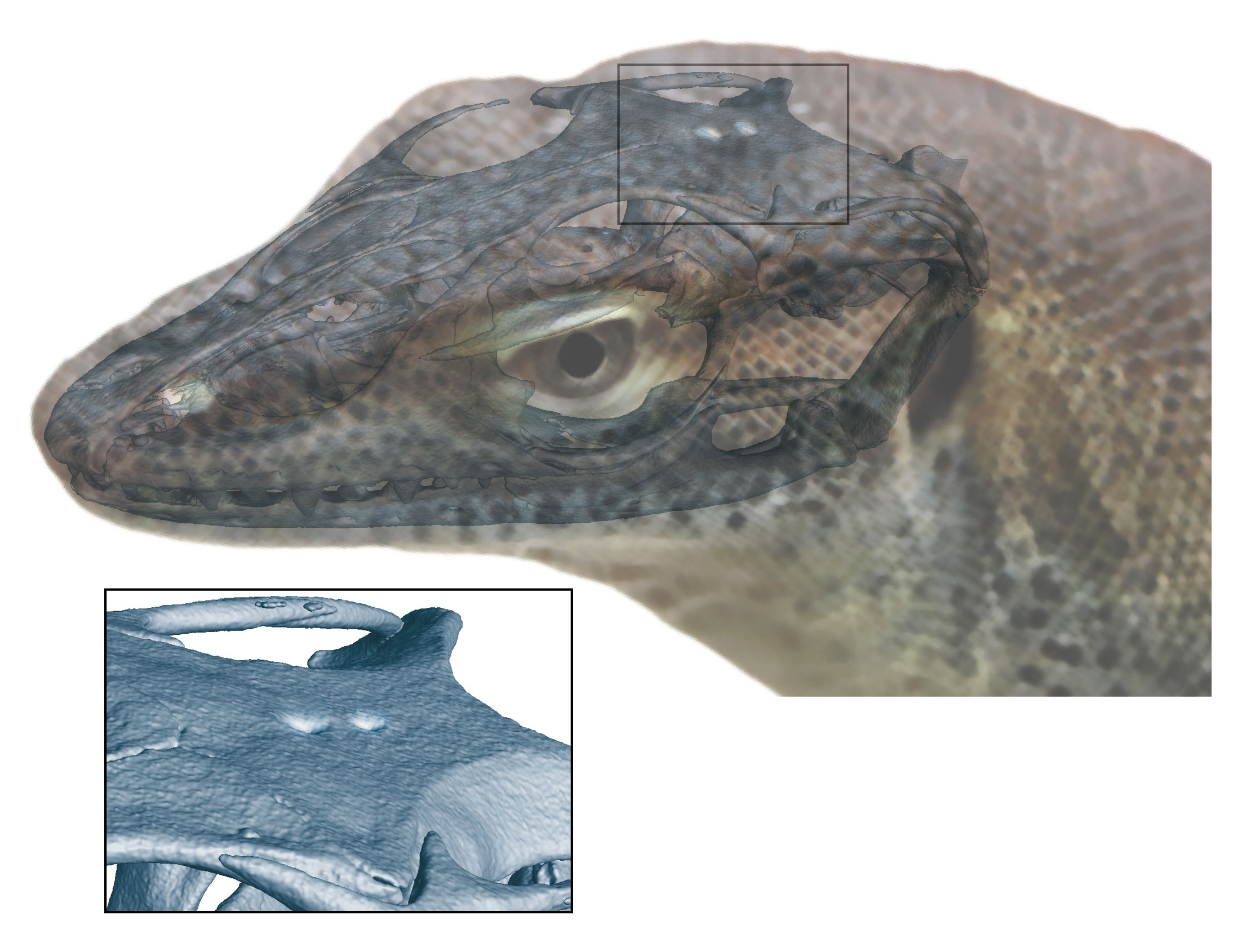

Contradicting reports about where the third eye was located on fossilized lizards led the researchers to investigate. They obtained museum specimens which had been collected nearly 150 years ago at Grizzly Buttes and performed CT scans.

The study revealed that two different fossilized lizards had a space not only for a third eye, but also for a fourth eye.

The research confirms that the pineal and parapineal glands were not a pair of organs the way that vertebrate eyes are. The outcome of this investigation also suggests that the third eye of lizards evolved independently of the third eye in other vertebrate groups.

Smith pointed out that these fossils, which had been laying around in a museum for over a century, had hidden value.

“The fossils that we studied were collected in 1871, and they are quite scrappy–really banged up,” said Smith. “One would be forgiven for looking at them and thinking that they must be useless. Our work shows that even small, fragmentary fossils can be enormously useful.”

The study is published in the journal Current Biology.

—

By Chrissy Sexton, Earth.com Staff Writer

Image Credit: Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung / Andreas Lachmann / Digimorph.org