Clownfish physically shrink their bodies to survive heatwaves

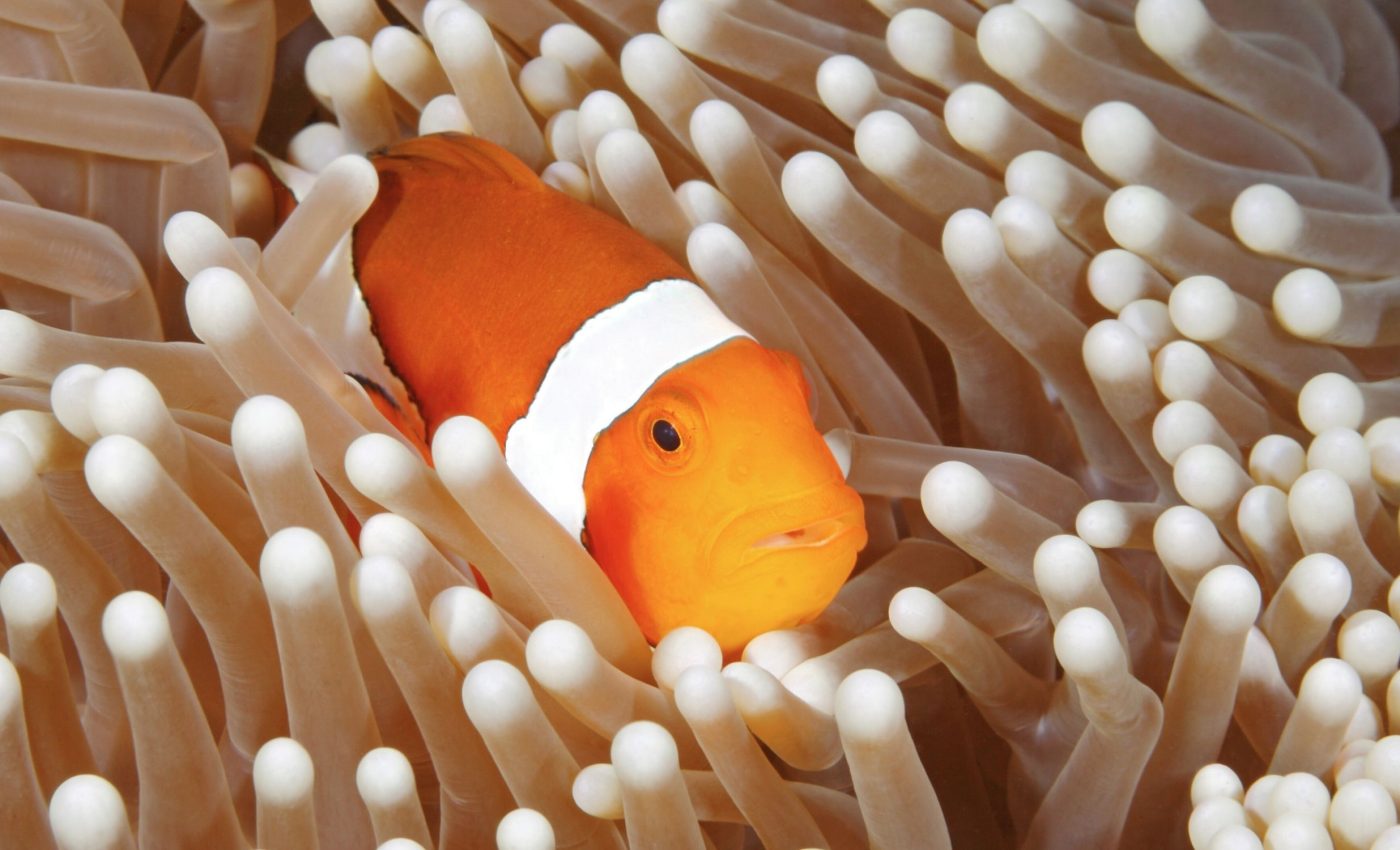

As oceans warm and coral reefs bleach, marine life must respond fast or disappear. Among the reef’s colorful residents, clownfish have shown an unexpected way to survive. These fish, famous from Finding Nemo, shrink their bodies during heatwaves.

This is not just about losing weight. Clownfish actually reduce their length, and it helps them stay alive.

A new study published in the journal Science Advances documents this discovery. Researchers from Newcastle University and partner institutions tracked 134 clownfish in Kimbe Bay, Papua New Guinea.

The study lasted five lunar months, during a time when water temperatures rose well above average. Researchers measured each fish and recorded the heat they experienced. The results were surprising and important.

Clownfish shrink their bodies to survive

Shrinking in adult vertebrates is rare. Yet during this study, 71 percent of dominant females and 79 percent of subordinate males shrank at least once. Most of these shrinkages happened during a single lunar month.

However, 41 percent of the fish shrank more than once. These were not accidents or isolated events. The response was consistent and widespread.

“This is not just about getting skinnier under stressful conditions, these fish are actually getting shorter. We don’t know yet exactly how they do it, but we do know that a few other animals can do this too,” noted Melissa Versteeg, the study’s lead author.

“For example, marine iguanas can reabsorb some of their bone material to also shrink during times of environmental stress.”

The shrinking was reversible. Some fish even showed catch-up growth later. This reveals a flexible growth system that adjusts based on current conditions. It allows fish to temporarily shrink and then grow again when conditions improve.

Higher-ranked clownfish shrink more often

The chance that a clownfish would shrink depended on its size and its social role. Larger dominant females started shrinking at around 80 mm (about 3.15 inches). Subordinate males began shrinking at about 61 mm (about 2.40 inches).

Larger fish have higher metabolic needs. Shrinking may help lower those demands during heat stress.

Shrinking also helps fish manage social tension. Within clownfish pairs, size ratios are important. If those ratios shift too much, conflict can arise.

Dominant fish were less likely to shrink when their partners were much smaller. This indicates a strategy that balances both physical survival and social peace.

Shrinking together helps fish survive

The study observed eleven deaths during the heatwave. Fish that shrank were more likely to survive. A single shrinking event improved survival chances by 78 percent.

All fish that shrank multiple times survived the entire study. The best survival rates occurred when both fish in a breeding pair shrank. Coordinated shrinking helped preserve social structure and reduced conflict.

“It was a surprise to see how rapidly clownfish can adapt to a changing environment and we witnessed how flexibly they regulated their size, as individuals and as breeding pairs, in response to heat stress as a successful technique to help them survive,” Versteeg said.

This behavior shows how social and environmental factors interact. Clownfish are not just reacting to heat. They are responding as pairs, and that cooperation improves their chances.

Heat stress triggers the change

The research found a direct link between local heat stress and growth changes. Fish exposed to higher temperatures during the same month showed some growth.

However, those who experienced high heat the previous month were more likely to shrink. This shows that shrinking can be a delayed reaction to stress.

“Our findings show that individual fish can shrink in response to heat stress, which is further impacted by social conflict, and that shrinking can lead to improving their chances of survival,” noted Dr. Theresa Rueger, senior author of the study.

“If individual shrinking were widespread and happening among different species of fish, it could provide a plausible alternative hypothesis for why the size many fish species is declining and further studies are needed in this area.”

This points to a new explanation for shrinking fish sizes across the world. It may not just be about juvenile growth or food shortages. Adult fish could be shrinking to survive.

Trade-offs of being smaller

While shrinking helps individuals survive, it may have long-term costs. In clownfish, reproductive output depends on body size. Smaller fish lay fewer eggs. So even if more fish survive a heatwave, fewer offspring may be produced.

Smaller fish may also offer less protection or nutrition to their host anemones. However, current evidence suggests that the number of fish matters more than their size in these partnerships. That means shrinking may not harm mutualism in the short term.

Many fish species might also shrink

Across ecosystems, scientists are seeing body sizes shrink. This is now considered one of three universal responses to climate change, along with changes in migration patterns and shifts in species distributions.

Most studies focus on changes across generations. But this research shows that adult fish can also change their size.

This means that shrinking might be happening more often than we think. The clownfish offers a clear, measurable example. Other reef fish that are site-attached and exposed to temperature extremes may do the same.

Clownfish shrinking is not fully understood

The exact mechanism behind clownfish shrinking remains unknown. It may involve tissue resorption or hormonal changes. In other animals, thyroid hormones drop during heat stress and affect growth. These possibilities need to be tested in lab conditions.

The gill-oxygen limitation theory also provides a clue. Larger bodies require more oxygen, but fish gills have a limited surface area.

Shrinking may help balance oxygen demand when temperatures rise. Alternatively, food shortages during heatwaves may make smaller bodies more energy-efficient.

Clownfish show new ways of adaption

Clownfish have shown that survival in a warming world might involve unexpected changes. They shrink in response to heat, and coordinate that change with their partner.

The fish adapt quickly and reversibly. This flexible response may help their populations persist, even as oceans grow hotter.

This discovery opens new questions. Are other reef fish using similar strategies? Can this plasticity be passed to future generations? And can we use this knowledge to better protect vulnerable reef communities?

One thing is clear. In the battle against climate change, even the smallest fish are making bold moves. Shrinking may not seem like much. But for the clownfish, it could be the difference between survival and extinction.

The study is published in the journal Science Advances.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–