Earliest evidence found of humans using the color blue for decoration

Color showed up in human history long before paintbrushes, fabric, or even writing. Thousands of years before ancient Egypt, in what is now Georgia, someone picked up a stone and crushed a blue plant that couldn’t be eaten.

From that act, we now have one of the earliest signs of the color blue – intentionally made by human hands.

Researchers have just confirmed that small pebbles found in Dzudzuana Cave, about 50 miles east of the Black Sea, were used 34,000 years ago to grind the leaves of a plant that produces indigo blue dye.

That’s long before we thought people were doing anything that complex with color. Turns out, they weren’t just hunting animals and gathering berries – they were already experimenting with plants in ways that go beyond survival.

Early humans knew plant power

For a long time, scientists assumed that Paleolithic people mainly used plants as food. But this discovery tells a different story.

A nonedible plant called Isatis tinctoria, or woad, left behind a signature chemical on ancient stone tools: indigotin. That’s the same compound that gives denim jeans their famous blue color.

Woad isn’t the easiest plant to work with. It doesn’t just ooze blue dye. You have to crush its leaves and expose them to air to start a chemical reaction. Only then does the indigo color appear.

The process involves knowing what part of the plant to use, how to treat it, and why. That implies that early humans already recognized this plant’s special qualities – and knew exactly how to release them.

Unexpected color in stone tools

The tools that revealed this were plain, rounded pebbles – unshaped by people. They were discovered in the 2000s, but it wasn’t until recently that archaeologists re-examined them.

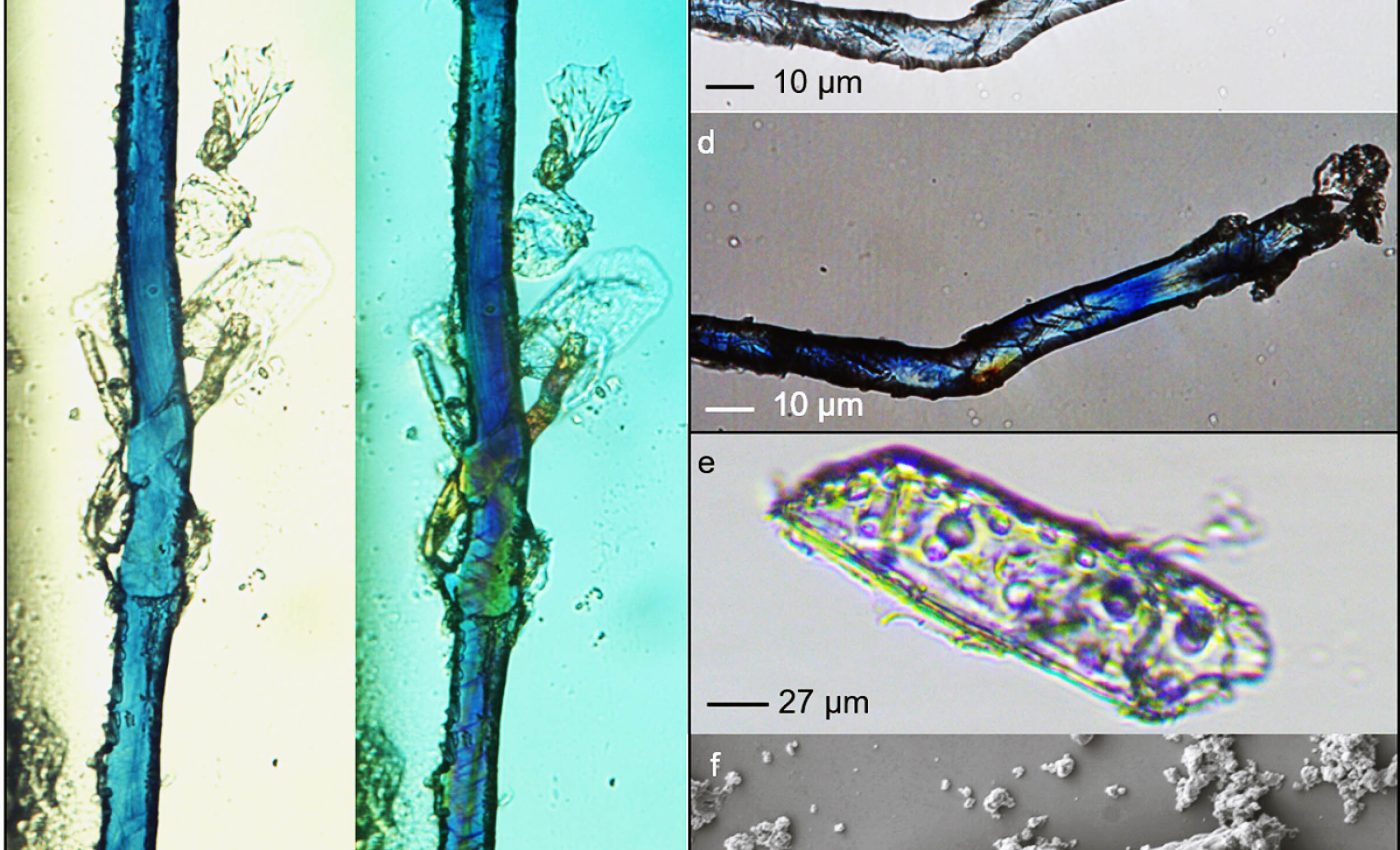

They weren’t looking for color at first and wanted to figure out how the tools were used. Were they for food? Leather? Plants? But under powerful microscopes, something unexpected showed up – tiny blue traces stuck in worn-down grooves of the stones.

These residues even looked fibrous in some spots, and they sat alongside starch grains – proof that plant material had been ground or rubbed.

To figure out exactly what the blue color substance was, researchers used Raman and FTIR spectroscopy – high-tech tools that can identify chemical compounds by how they interact with light.

Pores preserved plant remains

Finding color was only part of the puzzle. The next question was: how did the residue survive all this time? That’s where things got even more interesting.

The stones themselves had tiny pores – small enough to trap microscopic plant remains. Using synchrotron radiation (a super-powerful X-ray beam) and micro-CT scans, scientists could look inside the stones without breaking them open.

And yes, those pores had exactly the kind of shape and volume needed to hold the traces that were found.

Once they confirmed the tools could preserve those residues, the team tried to recreate what happened in that distant era.

Blue color on stones was made from plants

The team ran experiments using fresh woad grown and harvested in Italy. They crushed leaves on river pebbles collected near the cave and watched what happened.

The same kinds of blue residues formed on the stones. Some residues stuck in pores. Others left clear wear marks. And certain samples matched what researchers found in the original tools.

This wasn’t a random accident. It was a repeating process. Someone in the Upper Paleolithic knew how to create and use plant-based materials – even if they left no writing or instructions behind.

Color, medicine, or both?

No one can say for sure why they processed this plant. It might have been for color – maybe to stain animal hides, decorate tools, or mark territory. Or maybe it was for healing. Woad has a long history as a medicinal plant, used to treat wounds and infections.

Archaeologist Laura Longo of Ca’ Foscari University of Venice noted that plants are often viewed solely as food resources.

“This study highlights their role in complex operations, likely involving the transformation of perishable materials for use in different phases of daily life among Homo sapiens 34,000 years ago,” said Longo.

“While research continues to improve the identification of elusive plant-derived residues, typically absent from conventional studies, our multi-analytical approach opens new perspectives on the technological and cultural sophistication of Upper Paleolithic populations.”

Echoes of color in time

This discovery changes the way we think about our distant ancestors. They weren’t just trying to survive, they were thinking, testing, creating.

They were observing the natural world and determining how to use it in innovative ways – even using leaves to create lasting color.

We know that the motivation to build something beautiful or useful has been around for tens of thousands of years. And all it may take to validate that is a worn stone and a few spots of blue color dust.

The full study was published in the journal PLOS One.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–