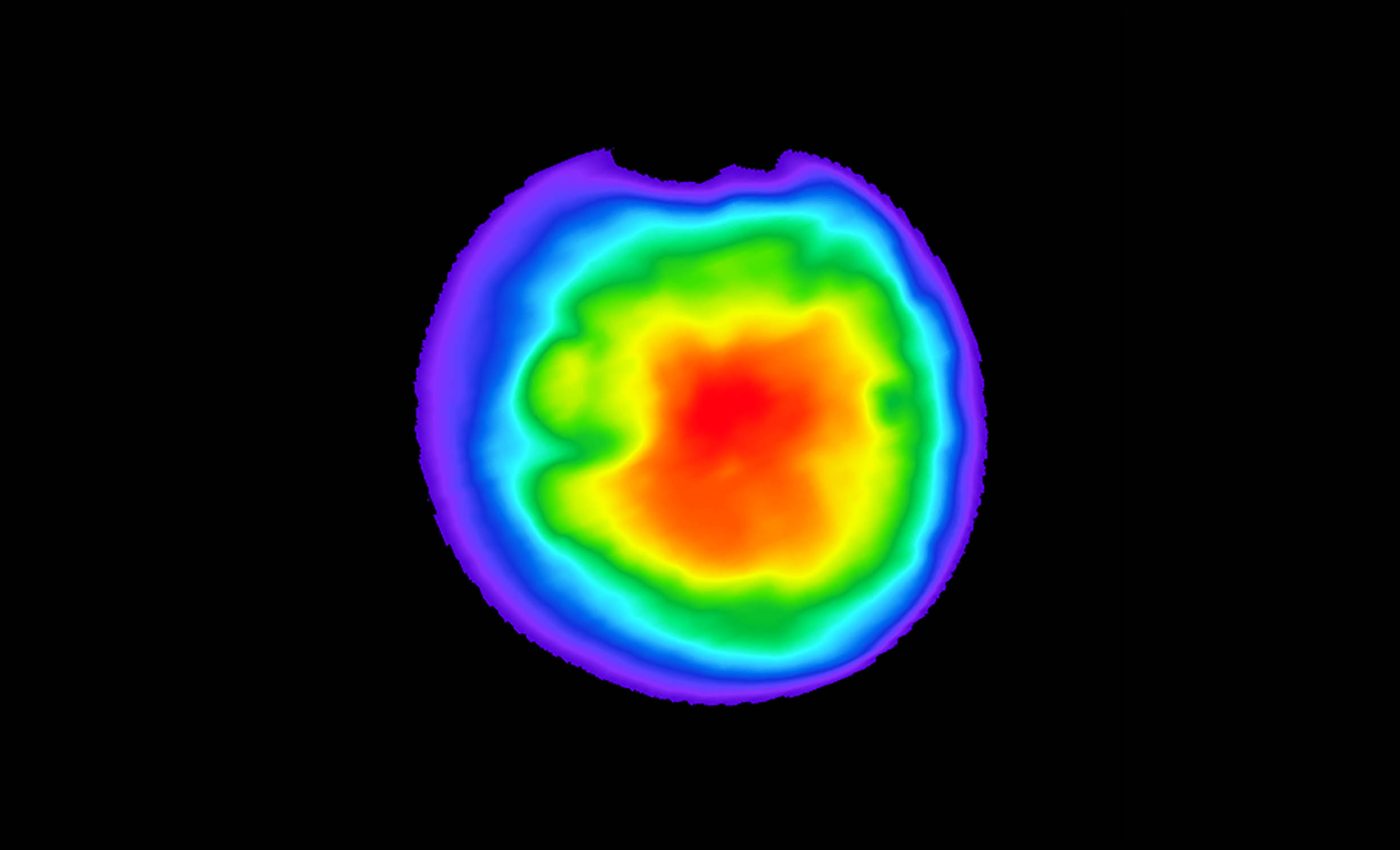

Europa Clipper captured Mars in thermal and infrared photos on its way to Jupiter's moon

Before heading to one of the most intriguing moons in our solar system, NASA’s Europa Clipper took a quick detour – and a few snapshots – during its recent flyby of Mars.

The mission used the opportunity to test one of its most important tools: an infrared camera that will later scan Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, for heat and hidden activity beneath its frozen shell.

Testing Europa Clipper’s eyes on Mars

The spacecraft passed just 550 miles (885 kilometers) above the Martian surface on March 1. This close approach wasn’t just for sightseeing. The team needed Mars’s gravity to give Europa Clipper a boost on its long journey to Jupiter.

But it also allowed researchers to put the spacecraft’s thermal imaging system to work, capturing over 1,000 grayscale images of the Red Planet.

These images, later colorized to represent warmer and cooler regions, will help scientists verify the instrument’s accuracy.

“We wanted no surprises in these new images,” said Arizona State University’s Phil Christensen, principal investigator of Europa Clipper’s infrared camera, called the Europa Thermal Imaging System (E-THEMIS).

“The goal was to capture imagery of a planetary body we know extraordinarily well and make sure the dataset looks exactly the way it should, based on 20 years of instruments documenting Mars.”

Thermal imaging for Europa Clipper

Europa Clipper’s real target is the icy moon of Jupiter – a world that may hide a global ocean beneath its crust. Scientists believe this ocean could be one of the most promising places in the solar system to search for signs of life.

Thermal imaging will play a crucial role in that search. When the spacecraft begins a series of 49 flybys of Europa, starting in 2030, its infrared camera will map the moon’s surface temperatures.

These temperature maps can reveal where the ice is unusually warmer, which may indicate recent geological activity or spots where the ocean lies close beneath the surface.

“We want to measure the temperature of those features,” Christensen explained. “If Europa is a really active place, those fractures will be warmer than the surrounding ice where the ocean comes close to the surface. Or if water erupted onto the surface hundreds to thousands of years ago, then those surfaces could still be relatively warm.”

Testing E-THEMIS with Mars data

Mars made an ideal test subject. Its surface has been studied for decades, making it easy to compare new images from E-THEMIS with past thermal data from other missions.

To be thorough, NASA’s Mars Odyssey orbiter – which carries a sibling instrument called THEMIS – collected its own images of Mars before, during, and after the Europa Clipper flyby. Comparing these datasets helps the team confirm that E-THEMIS is functioning as intended.

Radar and gravity tests along the way

Besides testing the thermal imaging system, the flyby gave the team a chance to check out the spacecraft’s radar components.

This was the first time engineers operated all the radar parts together in space. These antennas, which use long wavelengths, are too large to test fully in ground-based clean rooms.

Preliminary telemetry data from the radar systems looks promising, though more analysis is still underway.

The flyby also allowed the team to run communication tests. By transmitting signals through Mars’s gravitational field, they simulated the kind of gravity science experiments they hope to conduct at Europa. The results suggest those future experiments will work just fine.

Charting the course to Jupiter

The spacecraft began its journey on October 14, 2024, launching from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center aboard a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket. The 1.8 billion-mile (2.9 billion-kilometer) trip to Jupiter includes a few gravity assists – the Mars flyby being the first. The next assist will come from Earth in 2026.

Once it reaches the Jupiter system in 2030, Europa Clipper will orbit the planet and begin detailed observations of Europa.

The mission’s goals are to determine the thickness of Europa’s ice shell, examine how the surface interacts with the subsurface ocean, analyze the moon’s composition, and study its geology. By doing so, scientists hope to understand better whether Europa could support life.

Europa Clipper is led by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in partnership with the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. Arizona State University leads the development of the E-THEMIS instrument, which is essential for detecting thermal variations across Europa’s icy terrain.

Information for this article was obtained from a JPL press release.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–