Extraordinary new species of giant sea sponge discovered

A team surveying Ha Long Bay found a large sea sponge in a shadowed rock tunnel and realized it was new to science. It grows to about 8 inches across, looks like a cluster of short tubes, and carries a pale green tint.

The species has a formal name, Cladocroce pansinii, and it was collected during shallow dives along Vietnam’s northern coast.

Researchers gathered eight specimens and compared them with lookalikes from the wider Indo Pacific, then published their results in a peer reviewed study.

Finding Cladocroce pansinii

The Cladocroce pansinii sea sponge turned up in a semi dark passageway linked to a marine lake, a calm pocket of seawater hidden inside limestone. These quiet basins often host species that stay out of sight in open reefs.

Lead author credit is shared, but one organizer stands out in the fieldwork and analyses: Laura Núñez Pons from Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn in Naples, Italy (SZN).

A specialist in marine symbiosis and sponge biology, she coordinated the genetic work and species delimitation models that confirmed the discovery.

Her background in molecular ecology and chemical interactions among marine organisms helped the team bridge field observations with laboratory data, turning a curious dive find into a formally described species.

“Our work expands the knowledge of species distribution along iconic hotspots of the Indo Pacific Oceans and inspires research on marine biodiversity,” wrote Pons.

Why Cladocroce pansinii stands out

Cladocroce pansinii is bulky and tubular, with round openings that vent water. In the sheltered bay it stays compact, yet its form shifts in more exposed patches where currents push harder.

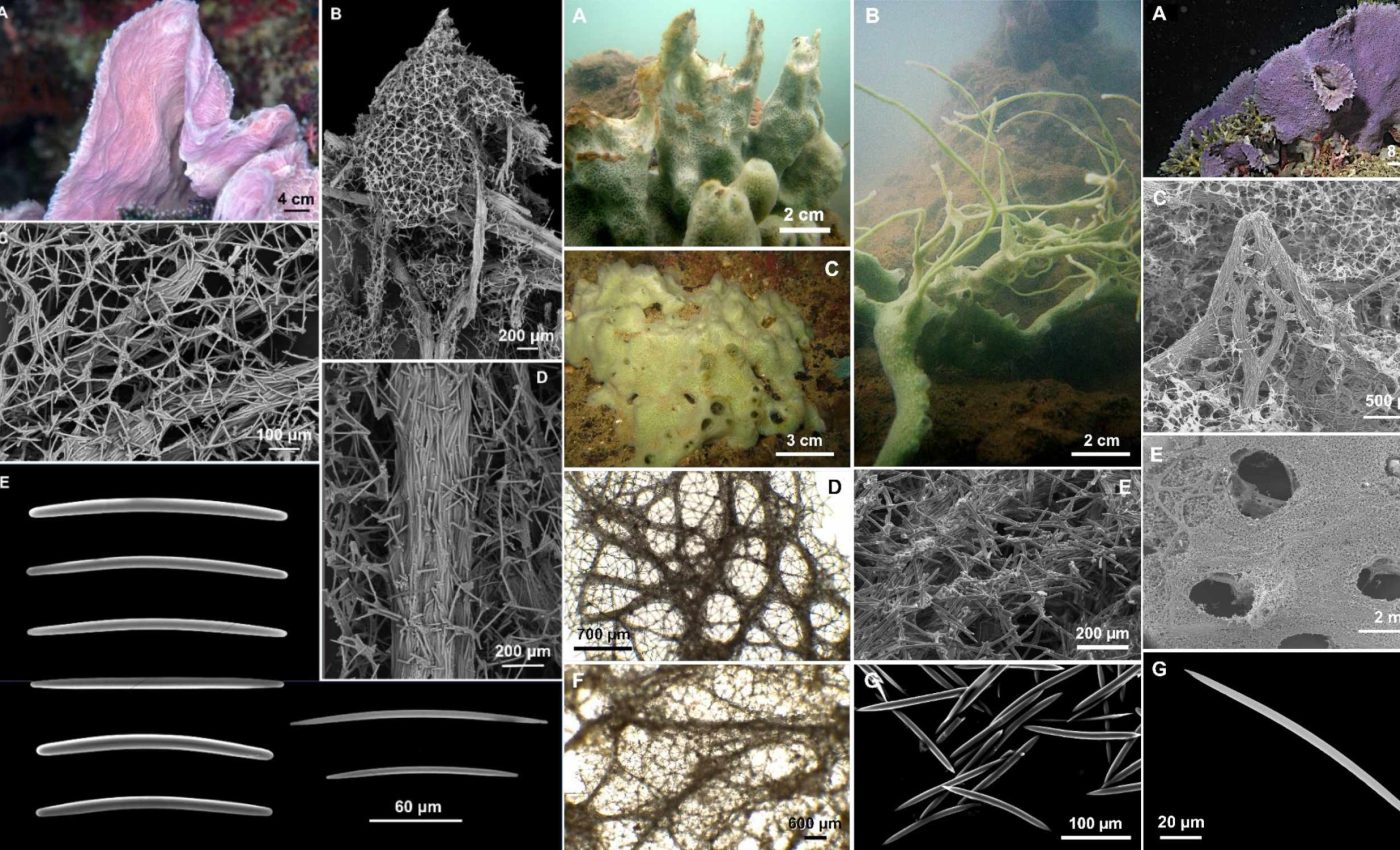

Its skeleton includes spicules, tiny silica needles that stiffen the body.

These spicules are longer and thicker than those of a close relative, Cladocroce burapha, and the internal fiber bundles form wider meshes that match the new species.

Clues hidden in DNA and shape

The team used integrative taxonomy, a method that combines DNA evidence with visible anatomy, to draw the species boundary cleanly.

Multiple lines of evidence converged on the same answer without relying on a single measurement or marker.

They sequenced several genetic regions and compared the patterns with museum vouchers. That approach reduced the risk of mixing local variation with true species differences, a common headache in sponge identification.

A 2017 Hawaiian sponge catalog listed a similar species from Kaneohe Bay as Cladocroce burapha. The new analysis shows those Hawaiian samples match C. pansinii instead, clearing up a case of mistaken identity.

That correction matters. It changes where scientists think each species lives, and it shifts how we read past ecological surveys that used the old names.

Weighing the genetics

The team tested three independent markers and ran species delimitation models that group sequences without prior labels.

Those models split the Vietnamese and Hawaiian samples from C. burapha, reinforcing the morphological call.

In sponges, mitochondrial COI barcoding, a quick DNA identification method, often lacks the power to separate close species cleanly, so multi locus evidence is more reliable.

Using several markers at once helped confirm that Cladocroce pansinii is distinct rather than a variable form of a known species.

Marine lakes sharpen the view

Ha Long Bay holds dozens of semi enclosed basins where salinity and temperature swing with the seasons. These basins can isolate populations for long stretches and nudge them along different evolutionary paths.

Recent population genetics findings show that enclosed marine lakes accelerate divergence in slow moving animals, including sponges.

Cladocroce pansinii home turf fits that pattern, with sheltered water and rock thresholds that limit exchange with the open bay.

How Cladocroce pansinii lives

C. pansinii sits in shallow water, about 7 to 13 feet deep, on rock and patchy reef bottoms. In quiet coves it sprawls as a low mat with thin branches, while on open faces it builds thicker tubes with neatly rimmed openings.

Color helps with field notes but not with naming. The new species is light green in Vietnam, yet related samples elsewhere can appear light blue or gray, which is one reason they were mislabeled before.

Sponges filter seawater constantly and move nutrients through reef food webs. When two species are lumped together, estimates of how much water they pump, or which microbes they host, can be skewed.

Clear names also guide conservation. If Cladocroce pansinii prefers semi enclosed lakes and C. burapha favors mangroves and calm bays, each will respond differently to heat waves, dredging, or freshwater surges.

What the find changes next

Museum curation locks in the identity of a new species by preserving type material. That anchor lets future teams sequence fresh samples and check their work against the original voucher without doubt.

The same mixed strategy that worked here, pairing traits with multiple genetic markers, is now standard practice in sponge systematics. It is also the safest way to compare species found in different countries and years.

One lesson from this study is practical. Single genes can mislead when species are young, separated only by a few mutations, or shaped by similar environments.

A second lesson is geographic. Semi-isolated lakes are natural laboratories for spotting splits that open water might hide. Those sites deserve regular monitoring and better baselines in feet, inches, and seasons.

The study is published in the Journal of Marine Science and Engineering.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–