Forgotten fossil turns out to be a new species of giant dinosaur

A fossilized skull, tucked in a museum drawer for more than a century, was determined to belong to a dinosaur nobody had named. The skull fragment has now been recognized as a new species of sauropod from what is now eastern Utah, and they have named it Athenar bermani.

Athenar bermani lived in the Late Jurassic in rocks of the Morrison Formation spread across the western United States.

The fossil was collected in 1913 at Carnegie Quarry in Dinosaur National Monument and stored at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh.

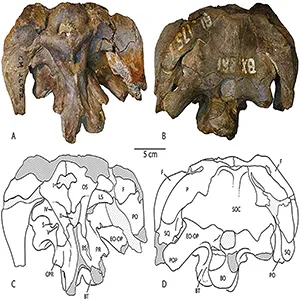

In the new study, researchers reexamined a fossil braincase and partial skull roof known as CM 26552.

Careful comparison with many other skulls showed that it did not fit the long snouted Diplodocus that it had been assigned to for decades.

The work was led by Dr. John A. Whitlock, paleontologist at Mount Aloysius College and the Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH).

His research focuses on how skull bones record the evolutionary relationships of long necked dinosaurs.

“Carnegie Museum of Natural History houses some of the most important specimens for our understanding of diplodocoid sauropod cranial anatomy,” said Whitlock.

For decades CM 26552 underpinned the textbook description of that dinosaur’s braincase, even though it actually belonged to a different branch of the family.

Why Athenar bermani is different

The name Athenar bermani honors both a musician and earlier researchers who studied similar fossils.

Unlike classic giants such as Diplodocus or Apatosaurus, it belongs to the rarer dicraeosaurid, smaller sauropod with shorter neck and tall back spines.

Instead of matching Diplodocus, the skull shows a mix of traits that line up with dicraeosaurids found in South America and China.

One especially odd feature is a tiny bony tooth along a skull suture at the back of the head, which helps set Athenar apart.

Several parts of the back of the skull also point toward its new identity. For example, the braincase has openings in the bone roof and a hook shaped prong on the squamosal, skull bone near the jaw joint.

Understanding dicraeosaurids

Dicraeosaurids were once thought to be restricted mainly to parts of South America and a few sites in Africa.

Athenar bermani adds a solid North American representative to that group and helps show that these smaller sauropods were more widespread during the Late Jurassic than scientists used to think.

The skull features seen in this fossil help paleontologists track how certain bone structures changed as dicraeosaurids spread into different regions.

Those changes record shifts in diet, habitat, and body posture, giving researchers new material for understanding why this group took a different evolutionary path from their longer necked relatives.

Busy Jurassic neighborhood

Magnetostratigraphy, method that dates rock layers using magnetic reversals, pins the age of this layer at about 151 to 150 million years ago.

That timing makes Athenar one of the last long necked dinosaurs known from this slice of the Morrison Formation.

During that time, the region was a low lying landscape with rivers, floodplains, and patches of forest.

The formation preserves plant eaters like Apatosaurus and Stegosaurus, along with theropods, fast moving meat eating dinosaurs, such as Allosaurus.

Paleontologists already knew that this rock unit held an unusually high number of long necked species. Work on other fossils from the same formation has shown that sauropod diversity there rivals that of any other dinosaur bearing rock unit.

Lessons from Athenar bermani

This newly-named dinosaur, Athenar bermani, is known only from this single skull piece, yet that limited fossil still holds key clues.

Its holes, ridges, and sutures show how nerves and blood vessels ran through the head and how the skull compares with those of relatives.

Reexamining old collections is becoming just as important as digging up new sites.

Museum shelves around the world hold many specimens that were named or labeled when fewer dinosaurs were known and fewer comparative tools existed.

Modern work, including careful anatomical surveys and new types of digital imaging, can turn these older fossils into fresh sources of data.

In this case, a specimen that once defined the braincase of Diplodocus has instead revealed an entirely different dinosaur that shared its habitat.

The study is published in Palaeontologia Electronica.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–