Fossil discovery shows that Earth's first leeches were not blood suckers

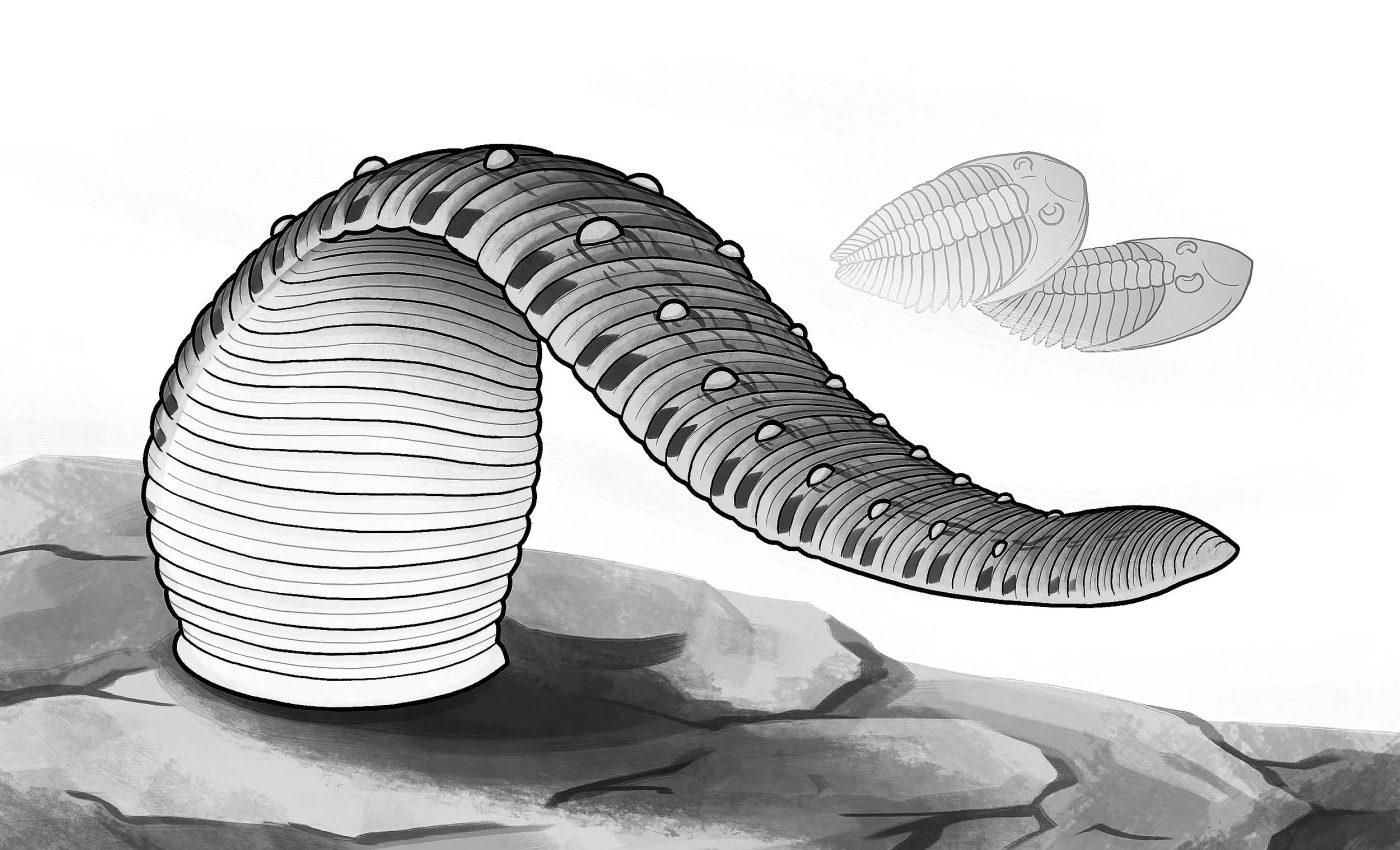

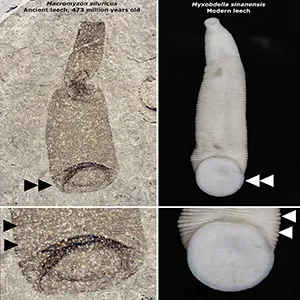

The fossil record rarely yields leeches. Their bodies are soft and fragile, built with almost nothing that fossilizes easily. So when one does appear, as with Macromyzon siluricus, it’s considered a lucky find pulled from the depths of time.

A fossil recently uncovered in Wisconsin has shifted the entire history of these animals. Scientists once thought leeches emerged in the Jurassic or Cretaceous.

Now, with this single specimen, the timeline stretches back more than 430 million years.

The discovery of Macromyzon siluricus seems to reveal that Earth’s earliest leeches lived in the ocean and were not the blood feeders we know today.

Macromyzon siluricus fossil find

“This is the only body fossil we’ve ever found of this entire group,” said Karma Nanglu, a paleontologist at the University of California, Riverside.

The fossil is remarkable for its preservation. It carries a teardrop-shaped body, clear segmentation, and a large caudal sucker at the rear.

Missing, however, is the forward sucker used by modern leeches to puncture skin. This absence, along with its marine origin, signals a completely different way of living.

Rather than drinking blood, this ancient leech likely swallowed soft-bodied creatures or drained their fluids.

“Blood feeding takes a lot of specialized machinery,” said Nanglu. “Anticoagulants, mouthparts, and digestive enzymes are complex adaptations. It makes more sense that early leeches were swallowing prey whole or maybe drinking the internal fluids of small, soft-bodied marine animals.”

The image is clear: the first leeches were not vampires of the sea but hunters of invertebrates.

Macromyzon siluricus rewrites timeline

Until now, the oldest direct evidence of leeches came from Triassic cocoons, around 200 million years old. Molecular clock studies placed their origin even later, in the Jurassic or Cretaceous.

Macromyzon siluricus tears through those estimates. At 437.5–436.5 million years old, it is more than twice as ancient.

Phylogenetic analyses confirm it as a stem leech – an early offshoot close to the root of the group. That makes it one of the most important fossils yet found for understanding the timing of clitellate origins.

Soft-bodied animals almost never make it into the fossil record. For Macromyzon siluricus to survive, it needed extraordinary circumstances. The Waukesha site provided them.

At this site, organisms were trapped in intertidal pools, buried quickly in low-oxygen sediment, and sometimes sealed by cyanobacterial mats.

“A rare animal and just the right environment to fossilize it – it’s like hitting the lottery twice,” Nanglu said. Without this unique preservation window, the fossil would have been lost like countless others.

Rethinking where leeches began

For decades, the consensus placed the earliest clitellates in freshwater.

The discovery of Macromyzon siluricus in a marine environment turns that idea upside down. It suggests the first leeches were ocean dwellers, with later groups moving into rivers and lakes.

Modern ocean-dwelling leeches, such as oceanobdelliforms, may carry that ancient heritage. Their place near the base of the leech family tree now seems less surprising.

Leeches today are often defined by parasitism. But was that always the case? The posterior sucker on Macromyzon could have helped it cling to surfaces or stabilize itself while feeding.

The ecosystem of Waukesha offers clues. Vertebrates were rare and small, unsuitable as hosts. Arthropods, especially trilobites, were abundant.

Given that some living leeches feed on arthropod hemolymph, it seems plausible that Macromyzon siluricus targeted invertebrates. If so, parasitism in leeches may have first evolved on invertebrates before shifting to vertebrates.

Why leech fossils are missing

Why are there almost no leech fossils between Macromyzon and the Triassic cocoons? Several reasons stand out. Ancient leeches may have lived in environments that rarely preserved soft tissue.

Their numbers could have remained low for millions of years, reducing fossil chances. Even when preserved, diagnostic features might not survive, making identification impossible.

This scarcity explains the massive gap in the record. The Silurian fossil does not just change the timeline – it shows how misleading absence in the fossil record can be.

Nanglu studies animals that almost never fossilize. For him, the discovery speaks to more than leeches.

“We don’t know nearly as much as we think we do,” he said. “This paper is a reminder that the tree of life has deep roots, and we’re just beginning to map them.”

“It’s a beautiful specimen,” he added. “And it’s telling us something we didn’t expect.”

The study is published in the journal PeerJ.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–