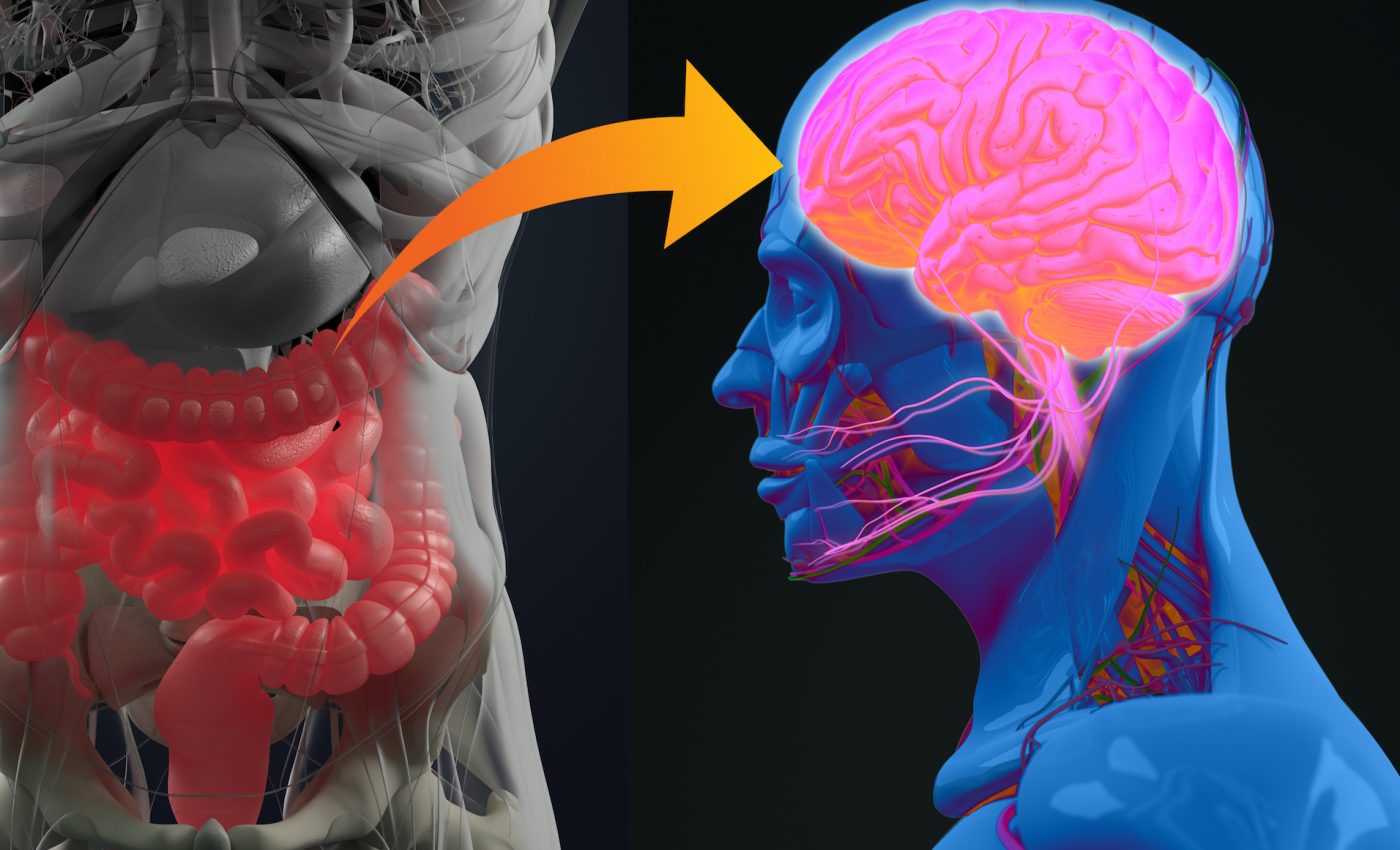

Sensors in the gut help the brain determine if we are hydrated

Researchers at UC San Francisco set out to investigate how your brain knows when you have had enough water and allows you to stop feeling thirsty. While the team had found in a previous study that there are sensors in the mouth and throat that assist in this process, the experts felt there were still unanswered questions.

“This fast signal from the mouth and throat appears to track how much you drink and match that to what your body needs,” said study lead author Christopher Zimmerman. “But we also knew that this fast signal couldn’t explain everything.”

In particular, the researchers wanted to understand how the brain knows the exact amount of hydration a certain drink will provide. For example, salty sea water does not quench thirst, but would activate many of the same receptors in the mouth and throat as drinking water.

The team implanted optical fibers near the hypothalamus of mice to watch the activity of thirst neurons while the animals drank salty water. As expected, the neurons ceased activity as soon as the thirsty animals took a drink. However, the neurons quickly switched back on, suggesting that some other sensor tested the water and sent out an alert to the brain that it was too salty.

The researchers speculated that these signals were coming from the gut. To investigate, liquid was distributed directly into the stomachs of thirsty mice while the experts observed the activity of the thirst neurons. The experiment revealed that delivering fresh water to the gut deactivated the cells the same way as taking a drink, but the thirst neurons remained active after salt water was delivered.

The findings suggest that the sensors in the mouth and throat signal the brain to temporarily quench thirst to reward animals for taking a drink, but the decision of whether the thirst is quenched is then reviewed by neurons based on a second round of signals from sensors in the gut.

“Interestingly, salt water didn’t drive drinking in well-hydrated mice, just in mice who were already thirsty,” said Zimmerman. “This suggests that signals from the gut are needed to quench thirst, but that you actually need to become dehydrated to trigger thirst in the first place.”

Dr. Zachary Knight is a neuroscientist and an associate professor of Physiology at UCSF.

“This is the first time we’ve been able to watch in real time as single neurons integrate signals from different parts of the body to control a behavior like drinking,” said Dr. Knight. “This opens the door to studying how all these signals interact, such as how stress or body temperature influences thirst and appetite.”

The research is published in the journal Nature.

—

By Chrissy Sexton, Earth.com Staff Writer