Disturbing discovery made on the deepest parts of the seafloor: "Not a single inch of it is clean"

The Mediterranean has long been a crossroads of trade and tourism, yet its deepest pocket, the Calypso Deep, seemed beyond the reach of day-to-day pollution.

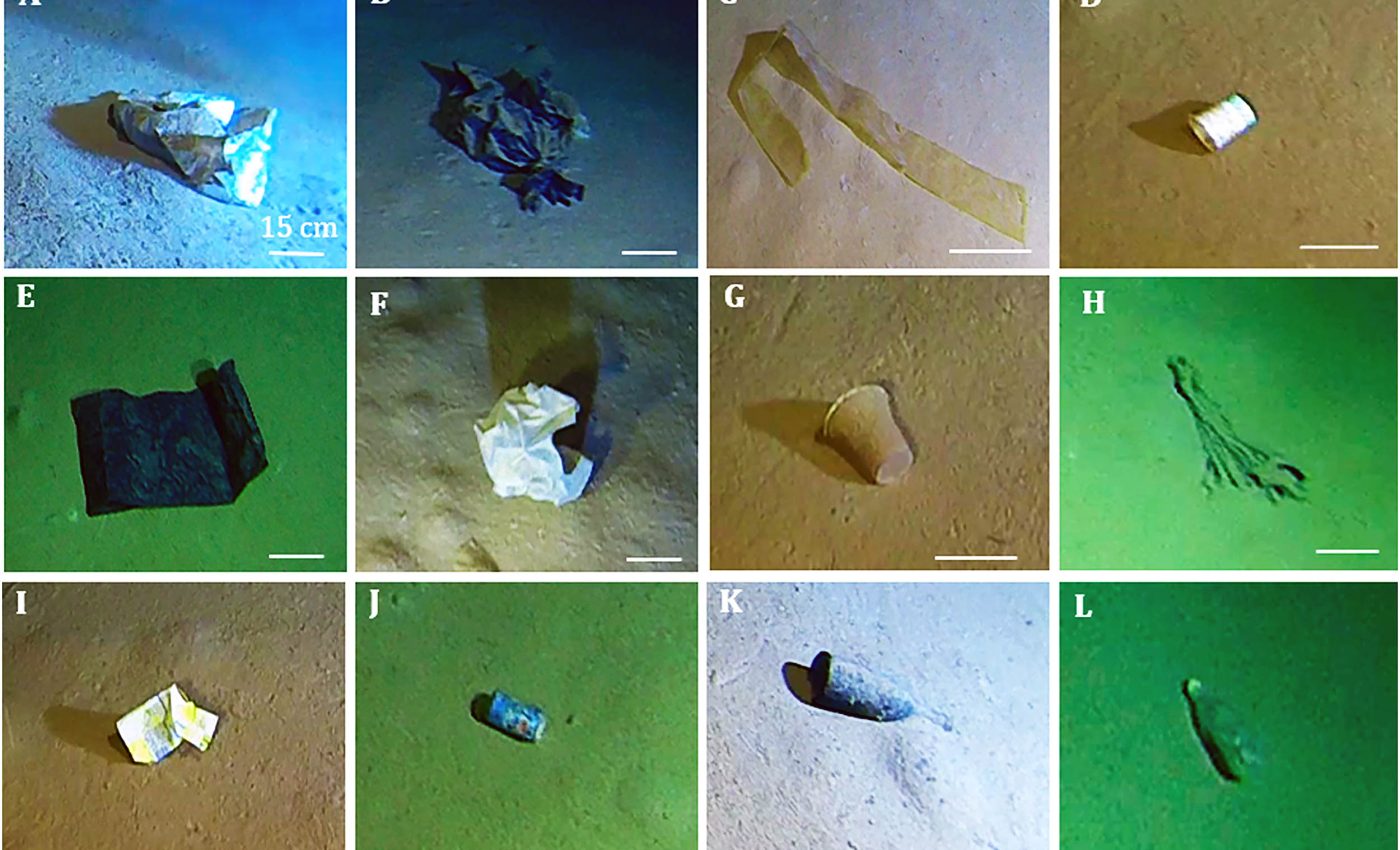

That hope ended earlier this year when researchers reported plastic bags, glass shards, and crumpled cans resting 16,770 feet beneath the waves in the Ionian Sea.

Their survey logged hundreds of items on the trench floor. By any measure, it is one of the densest concentrations of trash ever recorded in the dark zone of the ocean.

The discovery arrives as global attention continues to focus on plastic waste.

Videos of snagged sea turtles and bottle-strewn beaches have already ignited public concern, but those images barely hint at what sinks far below the reach of sunlight.

Now evidence from Calypso Deep shows that even the Mediterranean’s farthest recesses are filling up.

Calypso Deep is full of plastic waste

The team used the submersible Limiting Factor to reach the bottom of a kidney-shaped trench roughly 12.4 miles long and 3.1 miles across.

During a 43-minute trek near the seafloor of the Calypso Deep, cameras captured thousands of objects per square mile, mostly plastic waste discarded by humans.

A single straight-line pass of 2,130 feet was enough to confirm that human trash blankets large stretches of the basin. Most pieces were flexible plastics; glass, metal, and paper rounded out the list.

Even without animals caught on camera, the piles raise alarms because deep-sea communities recover slowly from disturbance.

Calypso Deep lies about 37 miles west of the Peloponnese coast inside the Hellenic Trench, a zone of steep, stepped walls prone to earthquakes.

Plastic waste rides currents

Weak currents, usually under 0.8 inches per second and rarely reaching 7 inches per second, let debris settle instead of sweeping it away.

“It comes from various sources, both terrestrial and marine. It could have arrived by various routes, including long-distance transport by ocean currents or direct dumping,” explains Miquel Canals, professor at the Department of Earth and Ocean Dynamics at the University of Barcelona.

“Some light waste, such as plastics, comes from the coast and escapes to Calypso Deep, just about 37 miles away. Certain plastics, like bags, drift just above the seabed until they are partially or completely buried or break down into smaller fragments,” Canals continued.

Rivers, wind, and ship traffic all feed the stream of refuse heading offshore. As algae and other organisms cling to floating polymers, the added weight turns buoyant scraps into sinking hazards. The trench’s closed shape then locks the pieces in place.

Calypso Deep as a plastic graveyard

Surface eddies often corral floating trash into the trench. When these eddies form over the Calypso Trench, some debris slowly falls to the bottom, aided by degradation and ballasting processes that increase its density.

Surface currents can also carry debris northward from the Adriatic Sea through the Strait of Otranto and from waters off northwestern Greece.

The same circular flows that drive marine life cycles are now channeling waste into permanent graveyards at the very bottom of Earth’s deepest bodies of water.

Earlier work in 2021 showed the Strait of Messina carrying the world’s heaviest load of undersea garbage, confirming that the Mediterranean is especially at risk.

“We have also found evidence of boats dumping bags of rubbish, indicated by piles of assorted waste followed by an almost straight furrow,” said Canals, expressing his frustration.

That is why the bottom of the Calypso Deep is littered with humans’ plastic waste, and also why the problem will do nothing but continue to worsen.

“Unfortunately, when it comes to the Mediterranean, it is fair to say that ‘not a single inch of it is clean.’”

Where do we go from here?

Unlike beaches and coastlines, the ocean floor remains largely out of sight, making it difficult to build social and political momentum for its conservation.

Yet what settles at the bottom can influence marine life, food webs, fisheries, climate feedback loops, and even geological stability.

The Mediterranean is an enclosed sea, surrounded by humanity, with intense maritime traffic and widespread fishing activity.

“Scientists, communicators, journalists, influencers – everyone with a platform – must work together. The problem is vast, even if it is not directly visible, and we cannot ignore it,” Canals implored.

The trail of refuse from shorelines to Calypso Deep underlines a plain truth: plastics and other debris do not vanish once tossed aside. They ride currents, sink in stages, and ultimately collect in the planet’s most secluded hollows.

The evidence provided by this research should galvanize global efforts – especially in the Mediterranean – to curb dumping, particularly of plastics, in line with the pending UN Global Plastics Treaty.

From the North Atlantic’s first recorded litter in 1975 to the record densities documented across the Mediterranean today, the pattern remains the same – human waste reaches everywhere water flows.

We must do more, we must do better, and we must do it now.

—–

Thanks to the leaders of this research team – Miquel Canals of the University of Barcelona, Georg Hanke of the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre, François Galgani of IFREMER, and Victor Vescovo of Caladan Oceanic

The full study was published in the journal Marine Pollution Bulletin.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–