Ancient Peruvian burial mounds flip the script on 'monumental architecture'

Monumental burial mounds or structures usually bring to mind kings, slaves, and ancient riches. Yet a windswept slope in southern Peru has just rewritten that script.

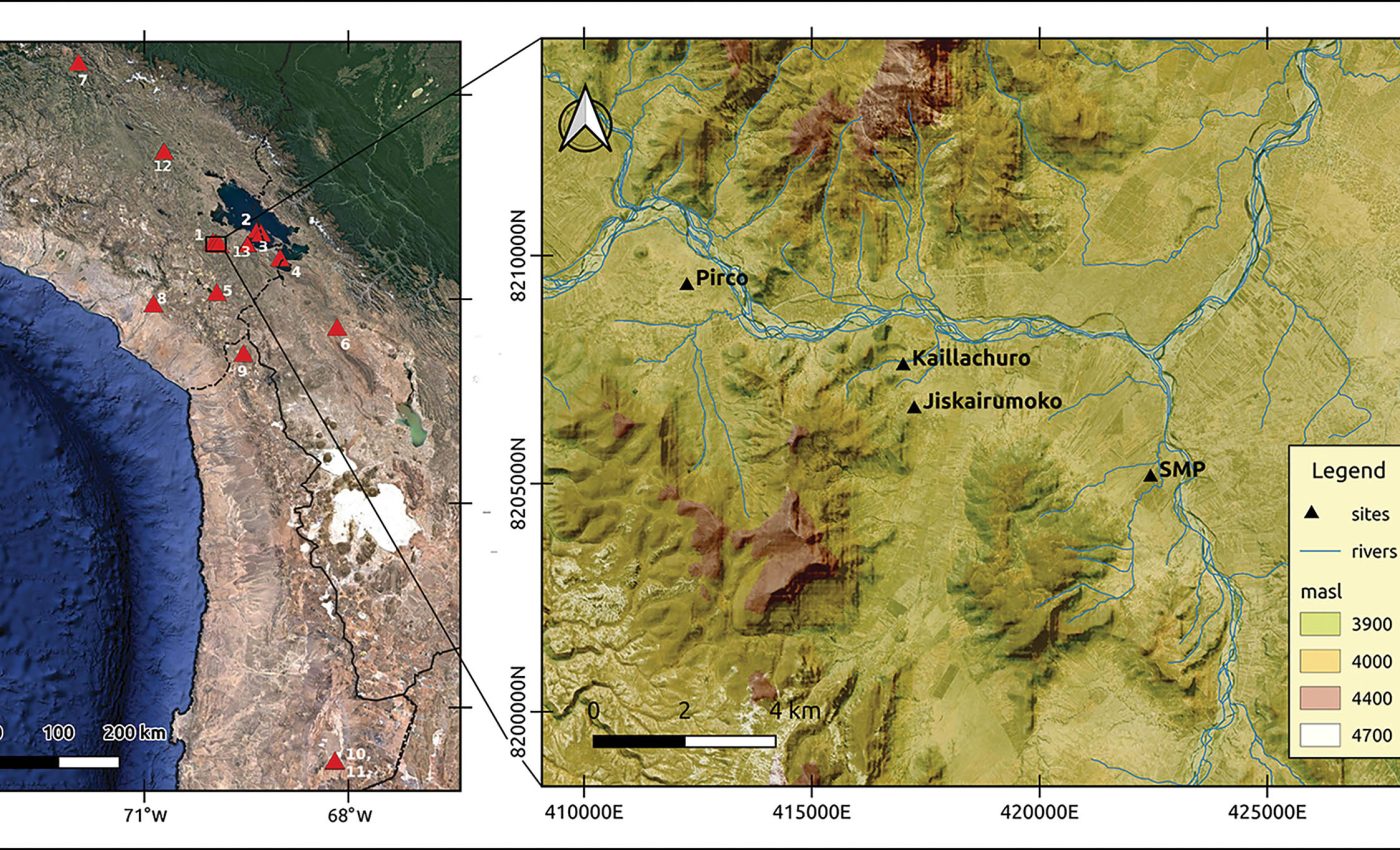

Archaeologists say the low ridges of earth at Kaillachuro, perched almost 13,000 feet above sea level, were raised by hunter‑gatherer families who had no kings at all.

Luis Flores‑Blanco of UC Davis, now at Arizona State University, led the research with co‑author Mark Aldenderfer of UC Merced.

Kaillachuro burial mounds

The team used radiocarbon dating to pinpoint the earliest construction at 5,300 calendar years before present, pushing the birth of monumental architecture in the Titicaca Basin back 1,500 years.

“Most researchers in the Andes argue that monumental architecture is a product of elites, intentionally constructed as a space of centralized power,” said Flores‑Blanco.

At Kaillachuro, nine hump‑shaped mounds grew slowly as mourners returned to reopen graves, add fresh offerings, and top the soil with ash from ritual fires.

Each visit left only a dusting of charcoal and bone, yet over two millennia those layers stacked into ridges tall enough to catch the sun from miles away.

Those incremental deposits thickened the landscape’s profile, transforming private grief into a visible landmark.

Ancient people of Kaillachuro

The builders camped on a terrace overlooking Lake Titicaca, a high‑altitude basin dotted with camelids and quinoa greens.

Seasonal stays lengthened into multi‑year residencies as groups experimented with tiny garden plots, swapped obsidian for wool, and learned to manage thin‑air farming.

Projectile points found in the fill link the mounds to the Terminal Archaic and Early Formative periods when the bow and arrow first appeared in the region.

Animal bone and burnt seeds scattered through the layers hint at feasts that mixed wild vicuña meat with roasted chenopod grains, fueling nights of singing and story‑telling beside the flames.

By 3,000 years ago the site was quiet, yet Inca mourners later slipped their own dead into the soft crowns of two mounds, underlining a tradition of reusing sacred ground. All this and more was able to be pierced together by the researchers.

Why hunters made gathering sites

And Kaillachuro is not the only case where mobile people raised heavy stone. Klaus Schmidt’s excavations at Göbekli Tepe in Turkey revealed T‑shaped pillars erected by pre‑agricultural bands more than 11,000 years ago, long before formal states emerged.

Closer to Lake Titicaca, the camp of Wilamaya Patjxa preserves graves that hold both women and men buried with hunting kits, pointing to unexpectedly complex social networks among Andean nomads.

Such parallels suggest that the urge to honor ancestors can unite scattered families, turning burial grounds into community magnets that slowly root people to one address.

Once gatherings became predictable, organizers could schedule food production, exchange tools, and share innovations that nudged society toward farming.

Kaillachuro mounds grew over time

Flores‑Blanco’s team traced five construction phases by reading subtle changes in soil color and texture.

The earliest was a simple pit trimmed with river stones and filled with ochre‑dusted bone; later builders set a child in a stone box lined with purple clay and sealed it tight.

During the third phase they leveled the summit, added a burned offering zone, and heaped soil into a cone more than four feet tall, a labor doable with baskets and family effort.

A nearby mound gained a low platform ringed by granite blocks, perhaps a stage for speeches, animal sacrifice, or recitations of lineage.

Radiocarbon ages from charcoal, bone, and camelid hair line up smoothly, showing activity spanned roughly 2,000 years without a gap longer than a human lifetime.

How archaeologists studied the mounds

Researchers walked every square yard of the three‑hectare terrace, then stitched hundreds of drone photos into a high‑resolution map.

Radiocarbon samples of bone, charcoal, and camelid hair were calibrated in OxCal 4.4, a free web tool that corrects for shifts in atmospheric carbon through time.

More than 76,000 flakes were counted through a one‑millimeter sieve, letting analysts plot where stone working happened and where feasting debris piled up.

Field seasons ran with permission from Peru’s Ministry of Culture and with daily help from the Jachaccachi Aymara community, who shared stories and guarded the trenches at night.

How graves shaped early communities

Archaeologists debate when South American societies crossed the line from loose bands to ranked villages. Kaillachuro lands in that gray zone, displaying communal works but no palaces, storerooms, or throne rooms.

If leaders existed, they probably led by persuasion and ritual knowledge rather than force, a style sometimes called “Big Man” authority.

Repeated cooperation at the cemetery could have trained families for larger tasks, laying the mental groundwork for later temple towns like Chiripa on the same lake shore.

The finding echoes work in other continents where mortuary gatherings preceded both agriculture and social stratification, hinting that grief may have been civilization’s first architect.

Questions remain about Kaillachuro

No house floors have yet surfaced, likely erased by modern plows, so archaeologists cannot say whether families lived beside their dead or walked in from satellite camps.

The study leaves open whether women, men, or specialized ritual leaders directed the ceremonies, because skeletal DNA from the mounds remains under analysis.

Future work may turn to microscopic plant starches and ancient DNA to track crop experiments hinted at in the charred seed fragments.

Laser surface scans planned for the next field season aim to pick out faint terrace walls that could mark gardens or corrals, tying ritual to daily economics.

For now, Kaillachuro reminds us that memories of loved ones can move more earth than kings.

The study is published in Antiquity.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–