Life on Earth before, during and after the dinosaur-killing asteroid strike

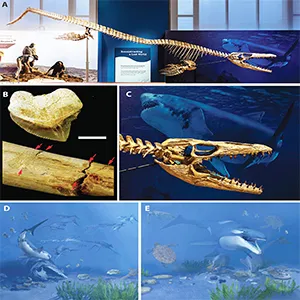

Sixty-six million years ago, what is now pine forest and bayou lay beneath a warm inland sea. In that Cretaceous Gulf, the apex hunters were mosasaurs – serpentine marine reptiles that could stretch nearly 50 feet nose to tail.

Research led by SMU paleontologist Michael J. Polcyn has compiled the first comprehensive portrait of these creatures in Louisiana, combining scattered fossil finds with seismic images and well cores.

“Louisiana is not known for having a great fossil record, but when you put it all together, it has a pretty interesting and valuable,” said team member Louis Jacobs.

Mosasaur in ancient seas

The rare Cretaceous exposures occur in Bienville Parish, where rising salt domes have tilted ancient strata to the surface.

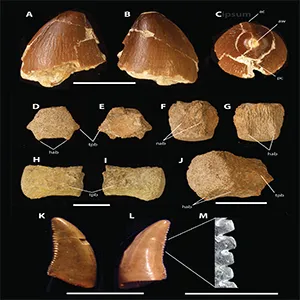

Among the few bones found is a strong tooth likely from Prognathodon, one of the largest and most powerful mosasaurs – a genus also uncovered by the SMU team along Angola’s coast.

This connection links Louisiana’s ancient sea directly to the newly forming South Atlantic Ocean basin of the same time period, indicating that these “sea lizards” once had a worldwide presence.

Disaster etched in the seabed

The marine idyll ended in seconds. When a six-mile-wide asteroid slammed into the Yucatán Peninsula, it vaporized rock, ignited worldwide firestorms, and launched tsunamis that echoed around the proto-Gulf.

The SMU-led survey records that violence in an unexpected place: underground. Seismic data gathered by co-author Gary L. Kinsland of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette reveals buried “ghost-maker megaripples.”

These tsunami-sculpted dunes stand about 52 feet high and stretch more than a third of a mile crest to crest – likely the largest on record.

“The seismic image showing the megaripples on the ancient seafloor is a wonderful illustration of the tremendous amount of energy introduced into the area by the impact tsunami in a very short period of time,” Polcyn said.

These ripples, frozen beneath younger sediments, serve as Louisiana’s signature of the Chicxulub impact that triggered Earth’s fifth mass extinction. They mark the exact horizon where mosasaurs, ammonites, and countless other Cretaceous species vanished.

Chance discovery reshapes the timeline

Fast-forward roughly three million years into the Paleocene, and the fossil record picks up a very different protagonist. An oil-well core drilled to 2,460 feet in central Louisiana pierced a layer dating to 63–62 million years ago.

Locked inside was the partial jaw of Anisonchus fortunatus – a hoofed mammal scarcely larger than a cat. The specimen, recovered by chance, underscores how quickly mammals occupied ecological space left vacant by dinosaurs. It also provides the young state with its oldest known terrestrial mammal.

Polcyn calls the little jaw a “striking bookend” to the extinction narrative. On one end is a tooth from an apex reptilian predator. On the other are the modest remains of a mammal poised to radiate across the planet.

“The contribution of this work reports the first Cretaceous marine reptile fossils known from Louisiana, putting them in a broader geographic and temporal context in the Gulf region,” he said.

Stitching the past together

The new synthesis is published in the journal Vertebrate Fossils of Louisiana, an LSU Museum of Natural Science tribute volume honoring the late paleontologist Judith A. Schiebout, who championed her adopted state’s fossil heritage.

Schiebout’s vision is realized in the way Polcyn, Jacobs, and their collaborators integrate multiple lines of evidence. These include museum collections, fresh fieldwork, well-core microscopy, and petroleum-industry seismic scans.

The result is a timeline stretching from the last flourishing of Cretaceous marine life, through the instantaneous destruction wrought by the asteroid, to the first stirrings of the “Age of Mammals.”

Mosasaur record connects continents

Although Louisiana contributes only snippets of bone, each piece lengthens a record that links North America to South America and Africa.

The same Prognathodon lineage patrolled both the Gulf and the South Atlantic, an insight made famous in the Smithsonian traveling exhibition “Sea Monsters Unearthed,” co-curated by SMU. Such parallels help paleontologists map ancient ocean currents, climate zones, and continental drift.

The impact story is likewise global. The Louisiana megaripples complement tsunami deposits in Texas and Mexico, collectively illustrating the reach of a single cosmic collision. For geologists today, ancient dunes reveal how quickly and powerfully energy moves through shallow seas.

Future fossil hunting in Louisiana

Polcyn hopes the compilation will spur more fossil hunting in a state better known for oil rigs than dinosaurs. Salt-dome uplifts, riverbanks, and drill cores still hide clues to life’s greatest turnover event.

“When you put it all together, it has a pretty interesting and valuable fossil record,” said Jacobs.

Each new discovery can refine models of extinction, recovery, and resilience – lessons increasingly relevant as modern ecosystems face rapid change.

From 50-foot mosasaurs to coin-sized mammal jaws, Louisiana’s deep past captures the drama of both endings and beginnings.

By piecing together shards of tooth, ripples of sand, and slivers of bone, scientists have illuminated how a once-tropical sea gave way to a landscape ready for jazz, shrimp boats, and human history.

But that transformation came only after a cosmic catastrophe rewrote the rules of life on Earth.

The findings were published in LSU Museum of Natural Science’s “Vertebrate Fossils of Louisiana” in a tribute to the late paleontologist Judith A. Schiebout.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–