Man is bitten over 100 times by cobras and mambas, leading to the creation of a universal antidote

Many people might shudder at the idea of coming into contact with a venomous snake. One man, Tim Friede, deliberately allowed himself to be bitten more than 100 times by cobras, mambas, and other lethal species.

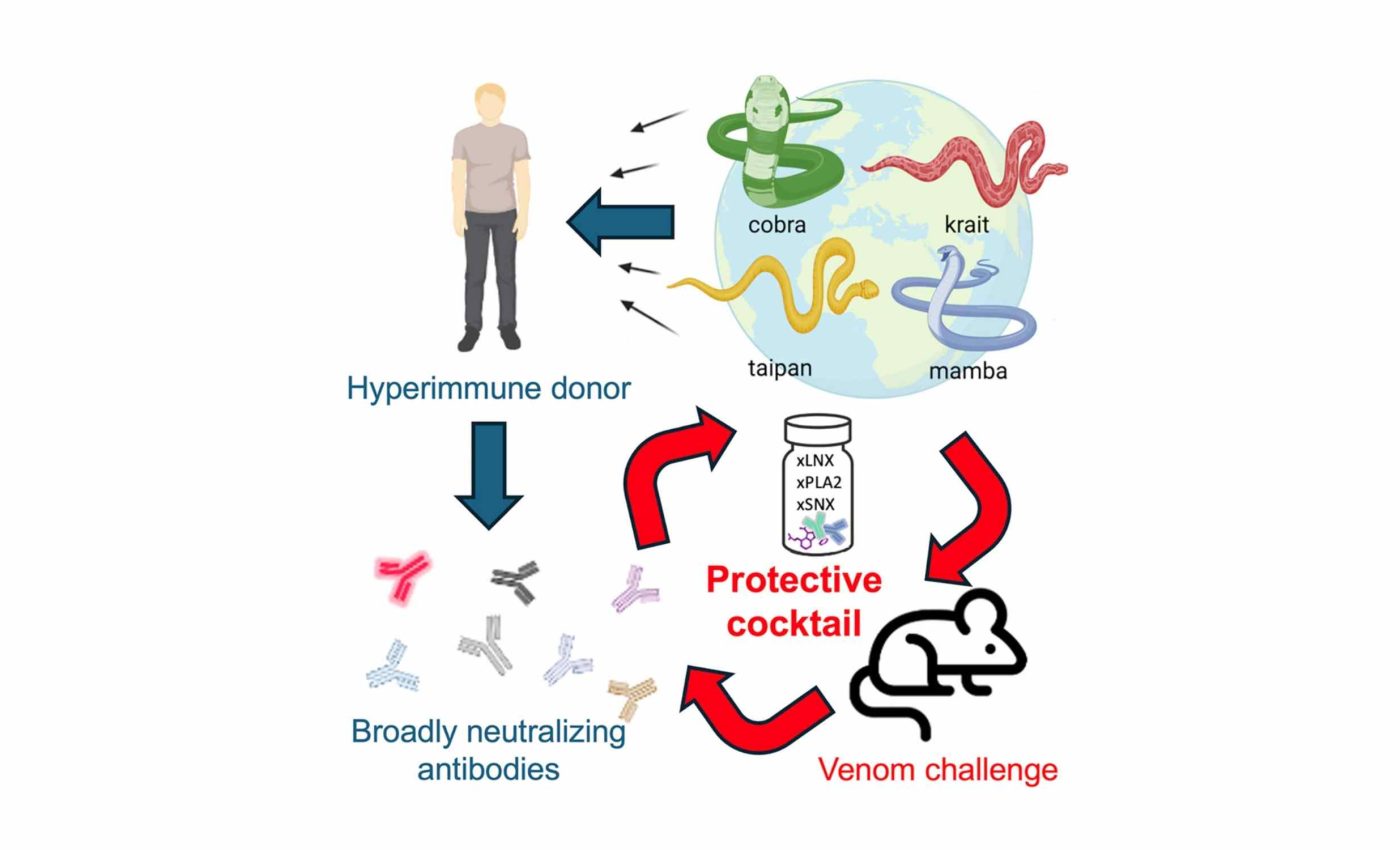

His actions were part of a personal quest to develop immunity that could save others from the effects of severe envenomation. The effort caught the attention of Dr. Jacob Glanville from Centivax, Inc., who decided to investigate the unique antibodies Tim had produced.

What snakebites do to the body

Every venomous snake has a cocktail of toxic proteins that harm the body in various ways. These toxins can disrupt nerve signals, break down tissues, or prevent blood from clotting.

Neurotoxins interfere with the nerve impulses that allow muscles to move, which can lead to paralysis or even breathing difficulties. This often results in swift and life-threatening complications if not treated promptly.

Challenges in existing snakebite treatments

Antivenom is traditionally manufactured by injecting horses or sheep with a specific type of snake venom, then collecting the antibodies they produce. This approach can be time-consuming and may offer limited coverage for different species.

Statistics from the World Health Organization show that snakebites kill thousands of people each year, with many more left disabled. In countries where multiple venomous snakes roam, a single product rarely provides adequate protection.

A bold path to immunity

“What was exciting about the donor was his once-in-a-lifetime unique immune history,” says Glanville. Tim Friede took a radical approach by letting his body learn to fight off venom from a range of snakes.

Instead of focusing on one species, Tim built antibodies that recognized toxins found in several. He became a living source of broad protection, which captured the interest of scientists aiming to craft a universal treatment formula.

Building a single snakebite therapy

The research team analyzed Tim’s blood to isolate antibodies that latch onto venom from various snake families. By targeting core toxic structures, these antibodies offer a more universal defense than older, region-specific remedies.

They also added a small molecule that blocks certain harmful enzymes, further preventing damage to muscle and nerve tissues. With these components combined, the therapy showed remarkable potential against multiple venoms in preclinical models.

How it works in tests

Trials in mice demonstrated that the blend could neutralize venom from black mambas, king cobras, and other snakes notorious for rapid fatalities. The fewer active ingredients made it simpler to fine-tune each dose.

Researchers plan to test the treatment on animals in clinics, particularly in areas like Australia where contact with venomous snakes is common. This approach is seen as a possible stepping stone to human trials.

Looking ahead

Work is already underway to adapt the technique for vipers, which account for many bites in Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Government agencies, philanthropic foundations, and pharmaceutical firms will be essential in making large-scale production a reality.

Many rural regions have scarce healthcare facilities, making snakebite injuries extremely dangerous. A widely accessible antivenom could reduce fatalities and long-term disabilities for vulnerable populations.

Economic and logistic hurdles

Creating antivenom requires specialized facilities, trained staff, and reliable access to venomous snakes, which can drive up production expenses. Even when an effective product exists, high costs and poor infrastructure can keep it out of reach in low-income areas.

In rural clinics, limited refrigeration and sporadic electricity can further complicate the storage of serums or specialized medical supplies. These bottlenecks lead to delays in treatment when every moment can be critical.

Transporting heavy or fragile products over unpaved roads adds another hurdle. Some public health programs lack consistent funding, so stable distribution networks are hard to maintain.

Global call to action

International organizations, including the World Health Organization, have emphasized the need for coordinated strategies to reduce snakebite deaths. They stress educational outreach, better funding, and improved production methods to meet urgent demands.

This universal antivenom initiative could spark interest among nonprofits looking to lessen the burden of neglected tropical diseases. Collaboration across multiple sectors might help accelerate trials and reach real-world patients faster.

Some regions have already introduced better training for healthcare workers, so they can recognize venomous bites quickly. Others are exploring mobile clinics and telemedicine to guide first responders in remote settings.

Future research and utililization

Researchers still need to explore how different immune systems might respond to this approach. Rare side effects or unexpected interactions with other medications could require careful study.

Additionally, producing enough consistent human-derived antibodies might pose unique difficulties. Monitoring long-term immunity and ensuring stable shelf life are also on the to-do list for scientists.

With continued cooperation and research, Tim Friede’s unorthodox immunization journey might lead to a single product that tackles multiple venom types in one go. This may mean that fewer lives would be lost to a global threat that frequently goes unnoticed until it is too late.

Researchers remain optimistic about the promise of broad-spectrum protection against snake venom. Although more work lies ahead, this collaborative effort could offer new hope where it is needed most.

The study is published in Cell.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–