Many young salmon break the typical migration rules, boosting survival chances

The story of salmon migration is often told as a single, determined journey. Young salmon hatch in freshwater streams, then swim downriver to the ocean. After years at sea, they return to the very river where their lives began, to spawn and restart the cycle.

But new research is challenging this narrative. Many young salmon, it turns out, aren’t sticking to a straight path.

A broader journey than expected

New research from NOAA Fisheries, Tribal scientists, and university scientists shows that up to 22 percent of juvenile salmon in California and Washington streams make unexpected detours.

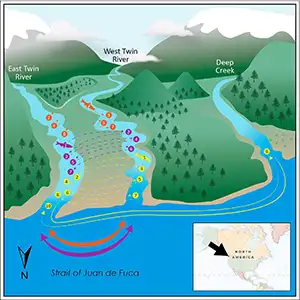

These young fish were tracked swimming down to the ocean and then back up into different rivers – some as many as nine times. In a few cases, they traveled as far as 40 miles (64 kilometers) up the coastline to entirely new rivers.

Rather than heading out to sea and staying there until adulthood, these juveniles wander. They criss-cross the coastal landscape, slipping between freshwater and saltwater as they explore their options.

“Stretches of coast and their rivers form enormous salmon nurseries for the exploring juveniles,” explained the researchers.

The team documented this pattern in coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch), as well as steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss), and cutthroat (Oncorhynchus clarkii) trout, all of which are salmonids . And they believe other salmon species may do the same.

How salmon use the coast for migration

The salmonids didn’t just travel at random. Some popped into unfamiliar rivers for short visits. Others spent entire seasons in new places.

The fish were seen using streams on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula and Northern California – places separated by long stretches of saltwater.

“The landscapes are much more connected than we realized, and salmon take advantage of that,” said Stuart Munsch, lead author of the study.

“This provides a more complete and accurate picture of the habitat they are using, which helps us make informed decisions as to how to promote their recovery.”

By testing out different rivers and streams, salmonids might find better shelter or more food. They might also be learning from each other – schooling with fish from different populations and picking up clues about where to find refuge or prey.

Stable habitats with new risks

Heavy rains in the Pacific Northwest can quickly turn peaceful streams into violent torrents. Water flow shifts rapidly, and vital stream features like wood and gravel can be swept away.

In such unstable environments, the ability to search out new, more stable habitats might be a lifesaver. But this behavior comes with danger. Young salmonids moving between fresh and saltwater become easier targets for predators.

“They’re perfect food for lots of other species, so they are taking a risk but also finding some benefits as they go,” said Todd Bennett, a salmon scientist at NOAA Fisheries’ Northwest Fisheries Science Center.

Still, the potential payoff may be worth it. Munsch noted that the young salmon and trout are searching for the best opportunities they can find.

“By moving around, they are also spreading the risk as some may find alternative habitats that better support them as conditions change,” said Munsch.

New questions about salmon behavior

It’s already known that adult salmon sometimes stray into different rivers than the ones they were born in. But could that behavior be shaped by their earlier wanderings as juveniles?

The scientists are still looking into that. They say more monitoring is needed to determine whether the rivers explored by juveniles affect where they return to spawn later in life.

What’s clear is that juvenile salmon are more mobile than previously assumed.

A closer look at salmonid migration

On the Olympic Peninsula, the researchers documented nearly 900 juvenile coho salmon, steelhead, and cutthroat trout moving between different river systems. Depending on the location and year, up to 22 percent of tagged fish were later detected in other rivers.

Most fish moved between just two rivers. But around 8 percent of them moved between three different systems, making up to nine distinct migrations during their juvenile years.

In Northern California, 28 coho salmon were recorded moving between river drainages. One even swam from a tributary of Redwood Creek to another stream feeding Humboldt Bay – a journey of about 40 miles (64 kilometers).

This behavior might not be unique to the U.S. Pacific Coast. The team reviewed other studies and found similar movements on three continents. That suggests it could be widespread.

Rethinking salmon management

Some of the salmonids followed routes commonly traveled by other fish. Others used paths that were rarely monitored.

Because the study could only track fish in rivers equipped with monitors, the researchers believe their findings may underestimate how many juveniles make these kinds of moves.

The takeaway? Scientists may need to revise how they think about salmon migration.

“We wouldn’t know about this unless we happened to be looking,” said Bennett. “Even after so many scientists have studied salmon over many decades, they still figure out how to surprise us.”

The full study was published in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–