More than half of the world's coastal communities are in retreat from rising seas

As seas continue to rise and storms grow fiercer, humans living in coastal communities are being forced to confront an age-old question in a new light: Where should we choose to live?

For millennia, coastlines have drawn people with promises of trade, food, and opportunity. But in the twenty-first century, the very shores that nurtured civilizations are becoming zones of risk.

What unfolds in this story is not only about climate change but also about inequality, adaptation, and the limits of human resilience.

Climate and coastal communities

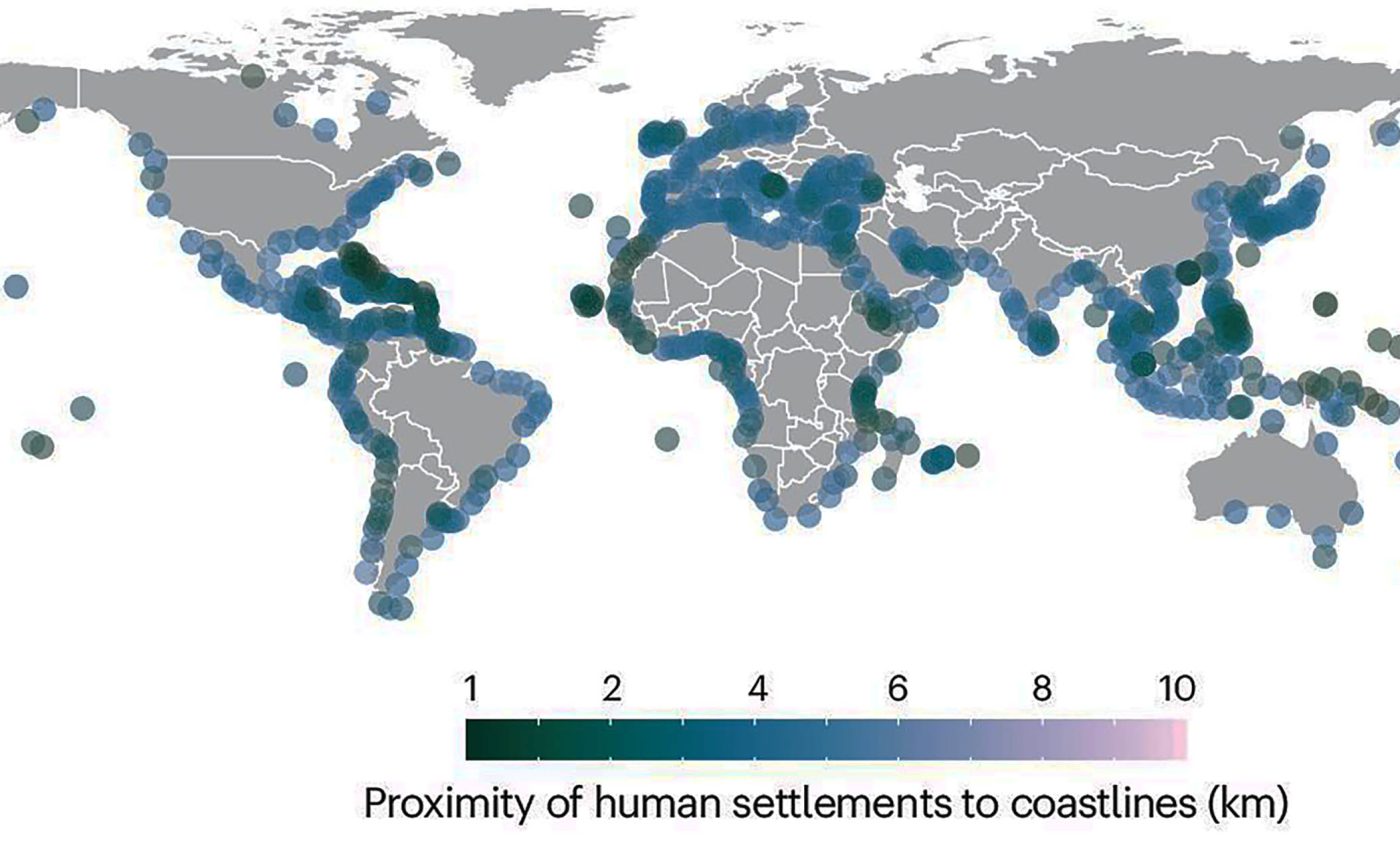

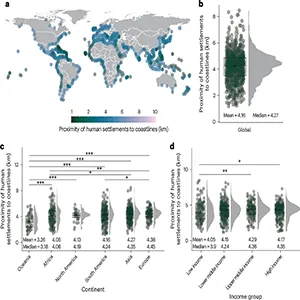

An international team of researchers has pieced together one of the most comprehensive views yet of human settlement change along coasts.

The study drew on nearly three decades of satellite nighttime light data, covering 1,071 coastal subnational regions in 155 countries between 1992 and 2019.

The findings reveal a complex, uneven picture. Overall, 56 percent of regions saw communities relocating inland, 28 percent remained fixed in place, and 16 percent experienced populations shifting closer to the sea.

These movements tell a story of adaptation but also of constraint. Wealthier groups often moved away, while poorer groups stayed or edged nearer, seeking livelihoods despite the risks.

Poverty and coastal pressure

Lead author Xiaoming Wang, adjunct professor at Monash University’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, captured this reality clearly.

“For the first time, we’ve mapped how human settlements are relocating from coasts around the world. It’s clear that moving inland is happening, but only where people have the means to do so,” said Wang.

“In poorer regions, people may have to be forced to stay exposed to climate risks, either for living or no capacity to move. These communities can face increasingly severe risk in a changing climate.”

The research shows that low-income regions are more likely to face rising exposure. Informal settlements grow near coasts, drawn by access to fishing, ports, and urban job opportunities.

Yet these communities are often built in fragile, hazard-prone areas, leaving them more vulnerable as climate change accelerates.

Coastal communities and inequality

The study tracked not only where people moved but also how quickly. By calculating annual changes in settlement proximity to coastlines, the team measured the pace of retreat or advance.

The results showed stark differences between continents and income levels.

Regions with strong institutional capacity and infrastructure protection managed quicker inland movements.

But where adaptive capacity was low, inland retreat slowed to a crawl. In fact, vulnerability – rather than past hazard experience – was the key driver.

The researchers argue that this reflects a fundamental gap in adaptation: not all societies can respond at the same pace, even when risks are clear.

Climate divides coastal communities

The geographic variations are striking. South America recorded the highest share of movements toward the coast at 17.7 percent, followed closely by Asia at 17.4 percent.

Europe, Oceania, Africa, and North America saw lower figures but still displayed uneven patterns across income groups.

In Africa and Asia, low-income regions often lacked resources to retreat inland. By contrast, high-income regions, such as parts of Europe, invested heavily in coastal defenses, which allowed settlements to remain near the shore.

This divergence underscores how wealth shapes choices: the same climate pressures produce very different responses depending on local capacity.

Wealth and risk collide in Oceania

Nowhere is this complexity clearer than Oceania. With some of the world’s closest settlements to the sea, the region relies heavily on fishing, tourism, and shipping economies.

Communities there often face impossible decisions, torn between livelihoods and survival.

“In Oceania, we see a common reality where wealthier and poorer communities are both likely to relocate towards coastlines in addition to moving inland,” Wang said.

“On one hand, the movement closer to coastlines can expose vulnerable populations to the impacts of storms, erosion, and sea-level rise. On the other hand, it can expose those wealthy communities to the growing coastal hazards.”

This dual movement highlights how culture, economy, and geography interact.

For many Pacific islands, relocation inland is constrained by limited land availability, meaning adaptation strategies must go beyond physical retreat.

Climate risks mislead communities

The research warns that infrastructure can create dangerous illusions. In Europe and North America, wealthy populations often chose to stay by the sea, trusting coastal defenses.

Yet this confidence can be misplaced. When levees and barriers encourage continued development, they may lock communities into high-risk zones.

“It is interesting to note that high-income groups also had a relatively higher likelihood to remain on coastlines, such as in Europe and North America. This can be due to their capacity and wealth accumulated in coastal areas,” Wang observed.

This paradox suggests that wealth does not guarantee safety. Instead, it may reinforce attachment to risky zones by making it seem possible to outbuild nature.

Planning beyond simple relocation

The researchers argue that the world cannot escape the growing necessity of managed retreat.

“Relocating away from the coast must be part of a long-term climate strategy, and the rationale for policy and planning to relocate people requires meticulous consideration of both economic and social implications,” Wang said.

This is not simply about moving people. It requires addressing inequality, protecting livelihoods, and improving informal settlements.

As the study stresses, adaptation must blend climate mitigation with local action. Without such balance, the adaptation gap will widen, leaving the poorest behind.

Global effort needed now

The work was a collaboration between Monash University, Sichuan University’s Institute for Disaster Management and Reconstruction, and partners in Denmark and Indonesia.

By bringing together expertise from engineering, disaster science, and climate studies, the team revealed not just where people are moving but why.

Their findings emphasize that humanity is not confronting a single coastline story. Instead, the picture is one of fragmented realities: some regions retreating, others clinging to coasts, and still others pulled closer by necessity.

The study challenges policymakers to view climate adaptation not as a uniform process but as a deeply uneven struggle shaped by wealth, vulnerability, and place.

The study is published in the journal Nature Climate Change.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–