MIT scientists invent new technology that grows much healthier fruits and vegetables

Farm chemicals often go everywhere except where farmers want them. A solution from Massachusetts involving silk microneedles could keep those nutrients right where the plants need them.

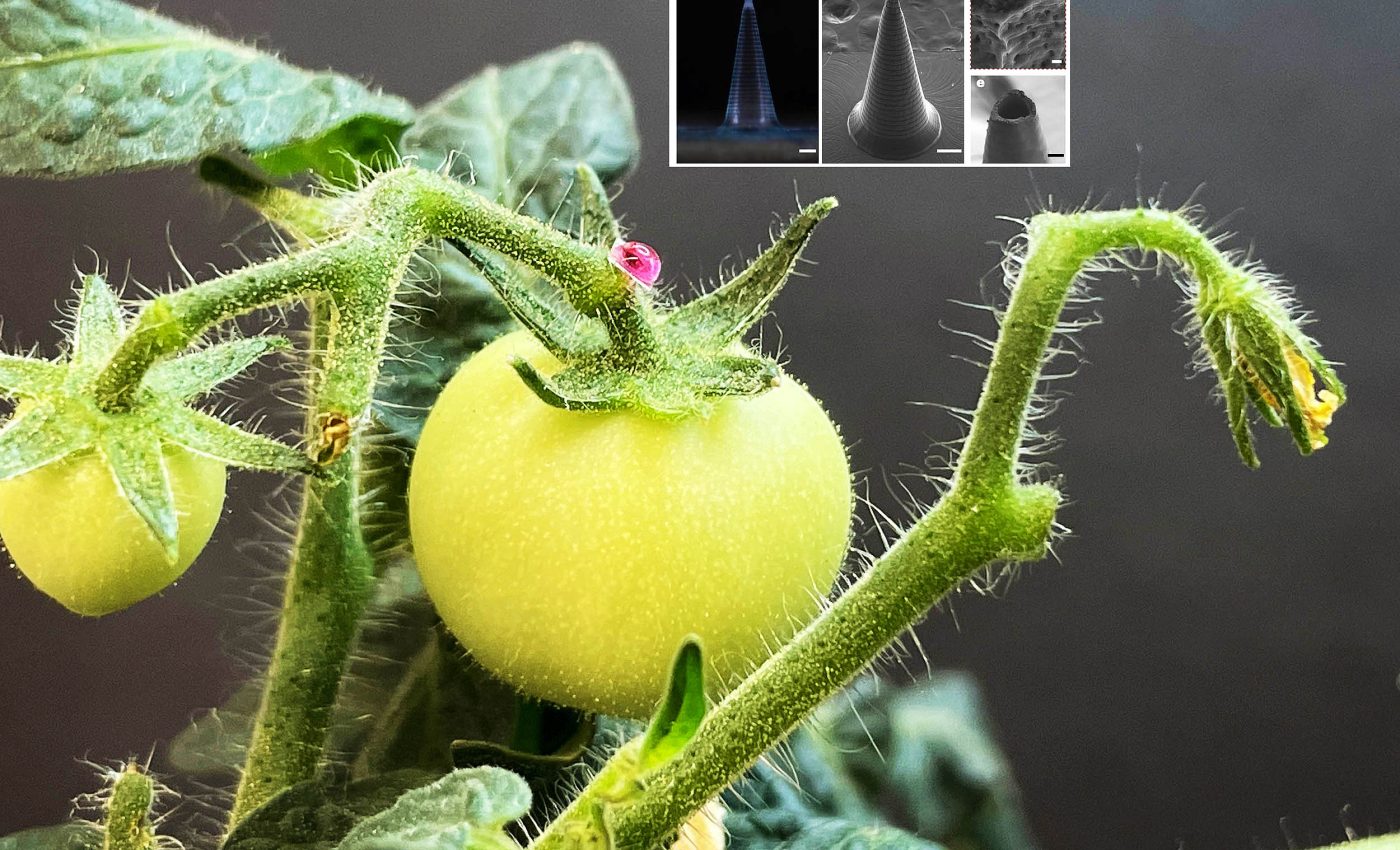

Associate professor Benedetto Marelli at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) leads a team that built microneedle arrays from silk to inject crops with various substances, including vitamins and minerals.

Their study, co‑authored with colleagues at the Singapore‑MIT Alliance for Research and Technology, was recently published.

Why silk makes sense

Silk fibroin is tough yet biodegradable, so it can pierce a tomato stalk without lingering in the field. When the fibers dissolve, they leave no shards to clog harvesters.

They pour a salty silk mix into cone‑shaped molds, let the water evaporate, then wash the salt away to reveal hollow microneedles. The cavity holds liquid nutrients that are ready for slow release.

“Graduate students can make thousands of tips in an afternoon, with no clean room. It can be done outside of a clean room, you could do it in your kitchen if you wanted,” ,” said Doyoon Kim, a former MIT postdoc.

Unlike metal or plastic, silk proteins are gentle on living tissue, an idea that first drew medical engineers to microneedles for painless vaccine delivery two decades ago. That gentleness matters for living stems.

Silk microneedles don’t prick the planet

Pesticide sprays and dusts drift on the wind or seep into groundwater. Reviews show that most of the active chemicals never reach their target leaves, instead soaking the soil and surrounding air.

In contrast, the microneedles anchor inside the plant’s vascular tissue and every milligram of pesticide stays put. That precision means farmers could use far less chemical per acre.

Kim injected iron into chlorotic tomatoes and found the yellowing reversed without any visible damage to the stems. The treatment ran for days because the hollow cores meter out the dose slowly.

“There’s a big need to make agriculture more efficient,” said Benedetto Marelli. Iron deficiency chlorosis can trim tomato yields by as much as thirty percent.

Boosting nutrition at the source

Silk needles are not limited to farm inputs; they carry human vitamins too. The team loaded vitamin B12, a nutrient absent from most plants, into the stalks of greenhouse tomatoes.

Lab tests confirmed that the vitamin traveled from stem to fruit before harvest, opening a path to on‑vine biofortification. That could help plant‑based eaters who struggle to meet B12 needs because the vitamin comes mainly from animal foods .

“This new delivery mechanism opens up a lot of potential applications, so we wanted to do something nobody had done before,” Marelli explained. The professor’s lab focuses on using sustainable materials.

The same approach could ferry zinc, iodine, or folate, reducing the cost of fortified staples that are now sprayed or blended after harvest. Researchers see similar potential for chili peppers and strawberries.

Silk microneedles for sample collection

The hollow silk microneedles also work in reverse, sipping sap for analysis. In hydroponic trials the needles detected cadmium in tomato stalks fifteen minutes after exposure.

Current spectral cameras spot stress only after leaves go pale, but sap sampling flags trouble while the crop still looks normal. Early warnings mean early fixes.

Researchers monitored cadmium levels over an 18‑hour window without removing the probes. Continuous readings beat labor‑intensive stem punctures that growers rarely perform.

With the right sensor package a robot could patrol rows, plug in a microneedle, and upload chemistry to a phone in real time. Such automation is already common in high‑tech greenhouses.

From lab bench to field rows

At present, a graduate student presses each patch onto a petiole by hand. Marelli imagines repurposing existing auto‑grafting arms or drone sprayers to stamp whole orchards.

“There shouldn’t be a trade‑off between the agriculture industry and the environment,” said Marelli. He argues for tools that boost yields without harming biodiversity.

Farmers, meanwhile, will want proof that the extra step pays for itself and that devices do not clog or snap during harvest. Field economics will depend on automating placement and refilling nutrient reservoirs without slowing crews.

Pilot tests on open‑air tomato plots are scheduled for the coming season, with attention to labor costs, residue testing, and yield bumps. Results will guide scale‑up strategies.

Are silk microneedles cost effective?

Silk cocoons are already spun at scale for surgical sutures, so the supply chain exists. Commodity prices fluctuate, but current estimates put the raw protein at a few cents per needle.

The molds can be reused hundreds of times, and the salt reagent is recovered and recycled. That circular chemistry keeps manufacturing overhead low.

Researchers calculate that a single greenhouse could recoup microneedle hardware costs within one harvest cycle if even a five‑percent yield gain holds true. Independent trials will verify those numbers under field stress.

Investors are interested because the technology fits within existing smart‑farm systems, pairing well with sensors and autonomous vehicles already roaming high‑value crops. Early venture funding talks are under way.

What comes next

The Massachusetts team is already talking with seed companies about combining the needles with seedling clips. That marriage could roll nutrition and monitoring into a single transplant step.

Beyond food, similar silk structures could deliver growth factors to tree seedlings in reforestation projects or vaccines to cash crops threatened by viral blights. Microneedles began in clinics and now stand to branch into orchards and vineyards.

Researchers in Singapore are evaluating whether the same platform can log plant hormones in rice paddies that are battered by heat waves. Their results will shape the next generation of silk microneedle sensors for climate‑ready farming.

Their journey shows how ideas migrate when materials meet imagination. If the field trials match the lab promise, tomorrow’s tomatoes might quietly get their vitamins straight from a silk straw.

The study is published in Nature Nanotechnology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–