Old photos help scientists predict ice shelf collapse and sea level rise

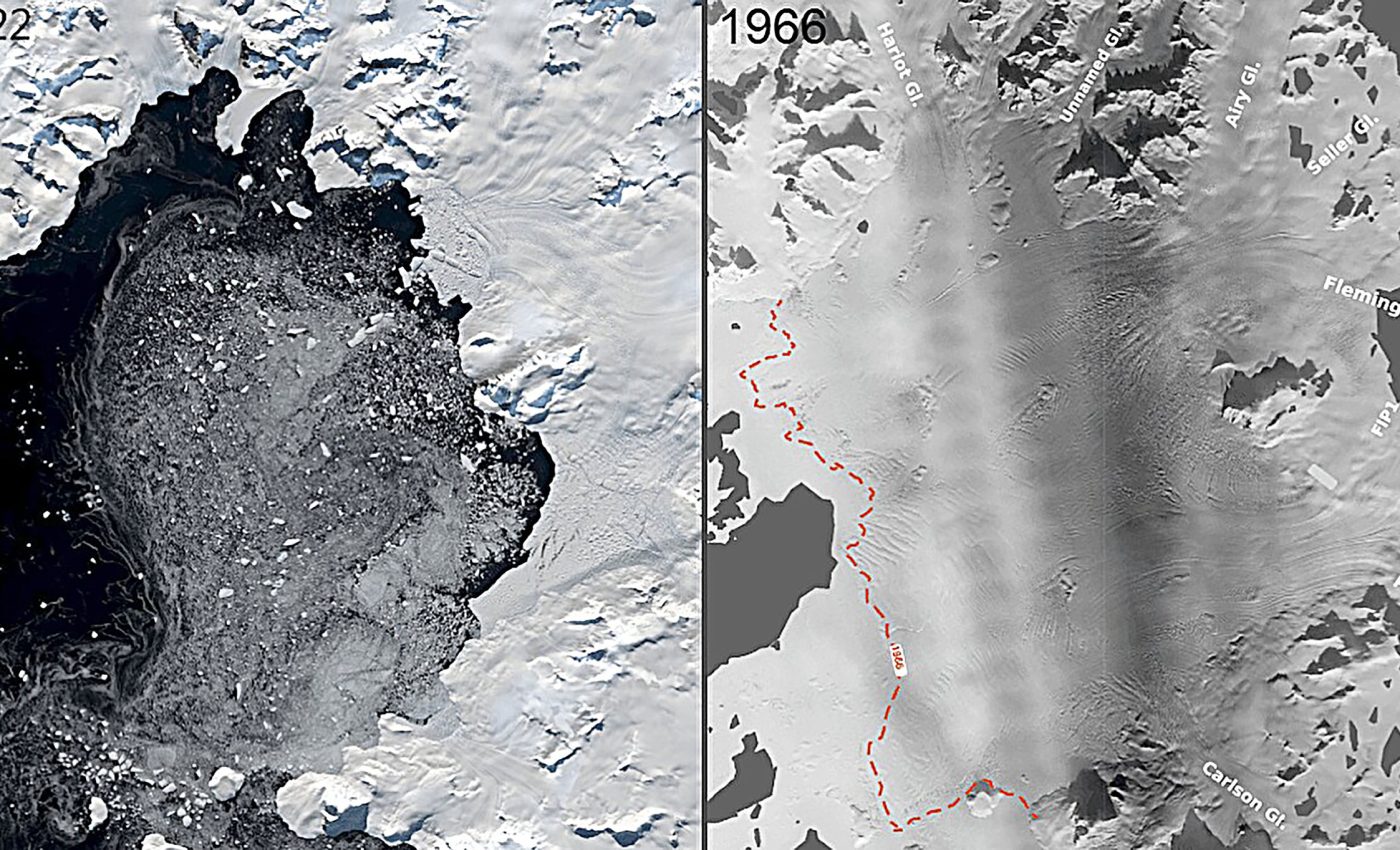

It started with a single ice shelf photo. On November 28, 1966, an American military plane flew over the Antarctic Peninsula, just south of Chile. A photographer onboard – likely from the U.S. Navy – snapped an image of the Wordie Ice Shelf.

At the time, no one knew that the ice shelf he photographed would almost completely collapse just 30 years later.

That image became the first in a long series of data points that are now helping researchers understand how and why ice shelves collapse – and what it could mean for our future.

From archives to data that matters

Scientists at the University of Copenhagen used that photo, along with hundreds more taken between 1966 and 1969, to reconstruct a detailed, time-lapsed view of the early stages of the Wordie Ice Shelf’s collapse.

The study merges the historical aerial photos with modern satellite data to track the long-term changes in the ice shelf’s size, shape, and behavior.

For the first time, this research documents the collapse of an ice shelf not as a sudden event, but as a long, evolving process. That shift in understanding matters.

“We have identified several signs of incipient ice shelf collapse that we expect will be observed in other ice shelves,” explained postdoc Mads Dømgaard from the Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management, who is lead author of the study.

“Perhaps more importantly, the dataset has given us a multitude of pinning points that can reveal how far advanced a collapse is. It’s a completely new tool that we can use to do reality checks on ice shelves that are at risk of collapsing or already in the process of collapsing.”

Ripple effects of the ice shelf collapse

The collapse of Wordie was relatively small in scale. It led to only millimeters of sea level rise. But it acted like a cork being popped. Without the support of the ice shelf, glaciers behind it were free to slide into the sea more easily.

That’s a major problem with larger ice shelves. Ronne and Ross – the two largest in Antarctica – hold back glaciers with enough ice to raise global sea levels by up to five meters.

While Antarctica may feel far away, its melting ice doesn’t just affect the Southern Hemisphere. Because of how gravity influences ocean distribution, ice loss in Antarctica leads to sea level rise in the Northern Hemisphere – including in places like Denmark.

What really caused the collapse?

To analyze the old images, researchers used a method called structure-from-motion photogrammetry. It stitches together overlapping photos to create detailed 3D models of the ice shelf’s surface, thickness, and movement over time.

They discovered something unexpected. Previous assumptions pointed to warmer air and the formation of meltwater lakes as the main culprits behind Wordie’s collapse. But the evidence from the current study tells a different story.

“Our findings show that the primary driver of Wordie’s collapse is rising sea temperatures, which have generated the melting beneath the floating ice shelf,” said Dømgaard.

In other words, it’s not what’s happening on top of the ice that matters most – it’s what’s happening below.

Surprising pace of ice shelf collapse

The study also challenges the common assumption that ice shelf collapses happen quickly.

“The tentative conclusion from our findings is that ice shelf collapse may be slower than we thought,” said Anders Anker Bjørk, assistant professor at the Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management.

“This means that the risk of a very rapid development of violent sea level rise from melting in Antarctica is slightly lower, based on knowledge from studies like this one.”

That sounds like good news, but it comes with a catch. According to Bjørk, the data shows a collapse process that is even more protracted than previously assumed.

“And this longer process will make it harder to reverse the trend once it has started. This is an unambiguous signal to prioritise halting greenhouse gas emissions now, rather than sometime in the future,” noted Bjørk.

The findings are a reminder that even slow-moving changes can carry enormous consequences. Understanding how ice shelves collapse gives us a chance to act – not later, but now – while we still have the choice to shape what happens next.

—–

Featured image credit: The Wordie Ice Shelf has undergone a total collapse since first photographed November 1966. Credit: Mads Dømgaard

The full study was published in the journal Nature Communications.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–