Only .001 percent of Earth's deep seafloor has ever been directly observed

Scientists have recently discovered that humans have recorded less than 0.001 percent of the deep seafloor – a surface that covers two-thirds of the planet.

The finding shows how little we really know about life and geology below 200 meters. The analysis comes from a study led by researchers at Ocean Discovery League and partner groups.

Using records from about 44,000 deep-sea dives since 1958, the team produced the first global estimate of visual coverage in deep water. They report that the total imaged area is only as large as the U.S. state of Rhode Island.

Vast depths still unexplored

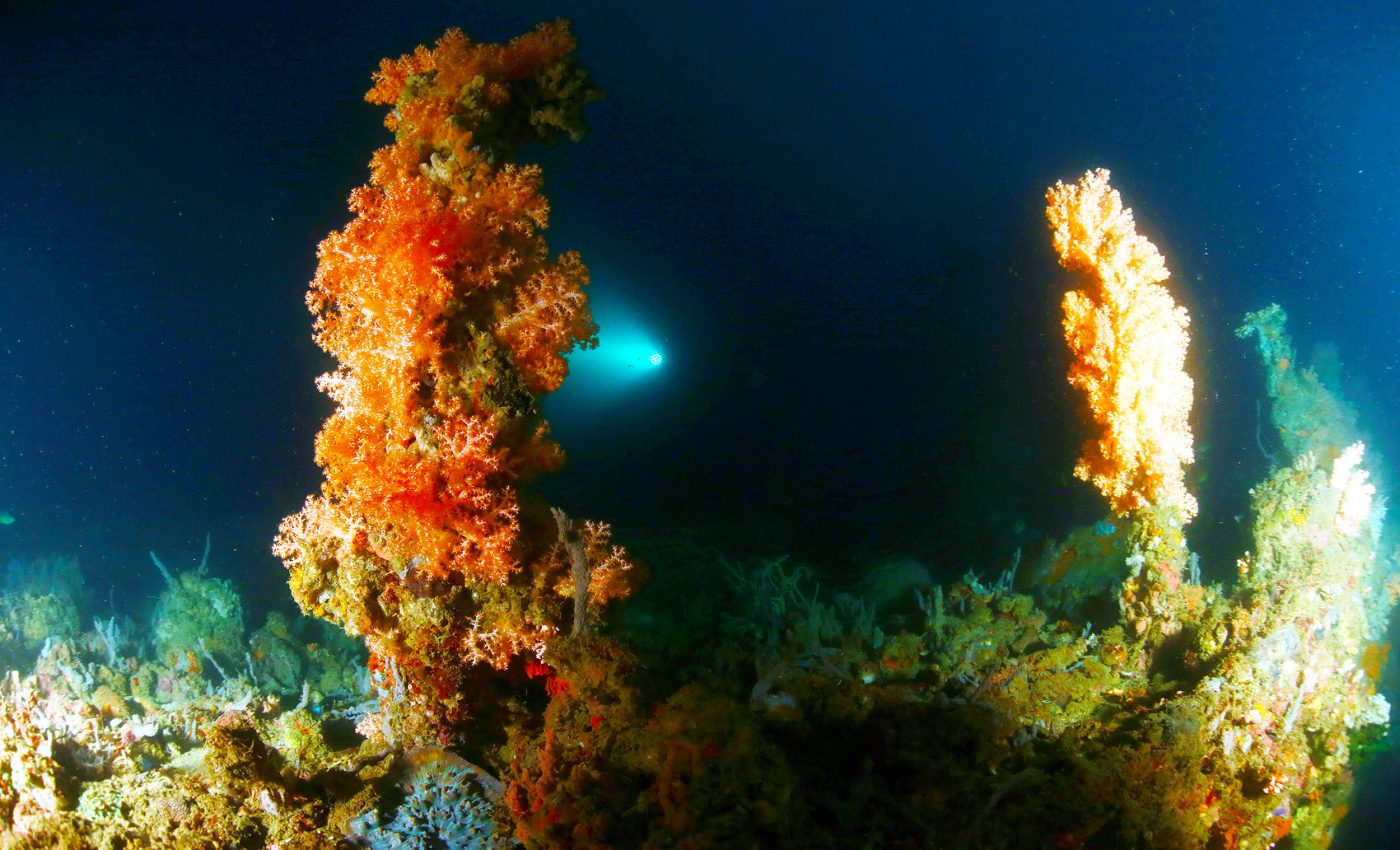

The deep ocean sustains rich ecosystems, moderates climate, produces much of Earth’s oxygen, and supplies molecules for new drugs.

Yet visual surveys of this realm remain rare and clustered around a few coastlines. Most dives have happened close to shore because far-off expeditions cost millions of dollars.

“As we face accelerated threats to the deep ocean – from climate change to potential mining and resource exploitation – this limited exploration of such a vast region becomes a critical problem for both science and policy,” said lead author Katy Croff Bell, the founder and president of the Ocean Discovery League.

“We need a much better understanding of the deep ocean’s ecosystems and processes to make informed decisions about resource management and conservation.”

Deep seafloor exploration is uneven

The researchers found that 65 percent of all visual observations happened within two-hundred nautical miles of only three nations.

The United States, Japan, and New Zealand dominate because they own or fund most deep-diving vehicles.

Five countries – the United States, Japan, New Zealand, France, and Germany – conducted ninety-seven percent of all recorded dives. That narrow sampling skews our picture of the deep sea.

Traits seen off California or Honshu may not describe conditions under the tropical Atlantic or the Southern Ocean.

Old images, low detail

Almost thirty percent of the dives logged by the study took place before 1980. Many produced only black-and-white still photos.

Today’s color and video systems can resolve tiny organisms and map fine sediment patterns, yet large parts of the ocean floor have never been filmed with modern gear.

Because many expedition logs are not public, the team tested how missing records might change the estimate.

Even if the true tally were ten times higher, they conclude, we would still have images for less than one-hundredth of one percent of the deep seafloor.

Uneven ocean habitat coverage

Canyons, ridges, and other dramatic features draw scientists because they are visually striking and may host rare species. In contrast, broad abyssal plains and many seamounts lie in silence and darkness.

Those plains hold most of the deep bottom, but they remain poorly sampled. Without clear data, researchers cannot judge how global warming, fishing gear, or planned seabed mining will alter these vast habitats.

The authors argue that cost, not curiosity, limits exploration. Deep-rated submersibles, remotely operated vehicles, and large research ships demand huge budgets. Technologists are now building smaller, cheaper robots and camera sleds that coastal labs can deploy.

Such systems could open doors for low- and middle-income nations. If more countries gather images from their own waters, the global map will fill in faster and with less bias.

The ocean is still a mystery

Ian Miller of the National Geographic Society noted that there is so much of our ocean that remains a mystery.

“Deep-sea exploration led by scientists and local communities is crucial to better understanding the planet’s largest ecosystem,” said Miller.

“Dr. Bell’s goals to equip global coastal communities with cutting-edge research and technology will ensure a more representative analysis of the deep sea. If we have a better understanding of our ocean, we are better able to conserve and protect it.”

A narrow view of a vast world

The paper offers a stark comparison: imagine trying to understand all land life on Earth by studying an area the size of Houston, Texas. That, the authors argue, is the scale of our current visual knowledge of the deep sea.

Without broader coverage, global policies on deep-sea mining, fishing, and climate mitigation rest on dangerously limited data.

To address this, the authors urge agencies, foundations, and industry to support large-scale imaging campaigns. They also call on researchers to share dive records openly – so that every frame of footage and every still image adds to a collective archive.

With shared data and open software, analysts worldwide could help identify new species, map coral gardens, or track drifting debris in deep-sea trenches.

Hope below the waves

Technological progress gives reason for optimism. Autonomous vehicles now fit in a suitcase and dive thousands of meters.

Machine learning can sort hours of deep seafloor footage in minutes. Fiber-optic cables on the seabed can detect passing animals through tiny pressure shifts. Taken together, these advances could multiply visual coverage within a decade.

The study marks a turning point in how society views the hidden majority of the planet. By revealing the gaps, the researchers have set clear targets for future work. Filling those gaps will require money, new machines, and global cooperation.

Yet the payoff could be immense: better climate forecasts, new medicines, wiser resource policy, and the thrill of discovery in places no human has ever seen.

The study is published in the journal Science Advances.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–