New fossil find shows robust human ancestor had huge thumbs that could make and use tools

A partial hominin skeleton from northern Kenya shows that an ancient ancestor of modern humans had the hands and feet to control simple tools. A new study ties the 1.52 million-year-old fossil bones to Paranthropus boisei.

The specimen comes from Koobi Fora on the eastern side of Lake Turkana. It links the species to human-like finger control while retaining heavy grip strength.

Clearer picture of an early human

Paranthropus boisei, a robust early human ancestor with huge chewing teeth, lived in East Africa between about 2.3 and 1 million years ago. The new bones finally move it from skulls and jaws to a clearer picture of the whole body.

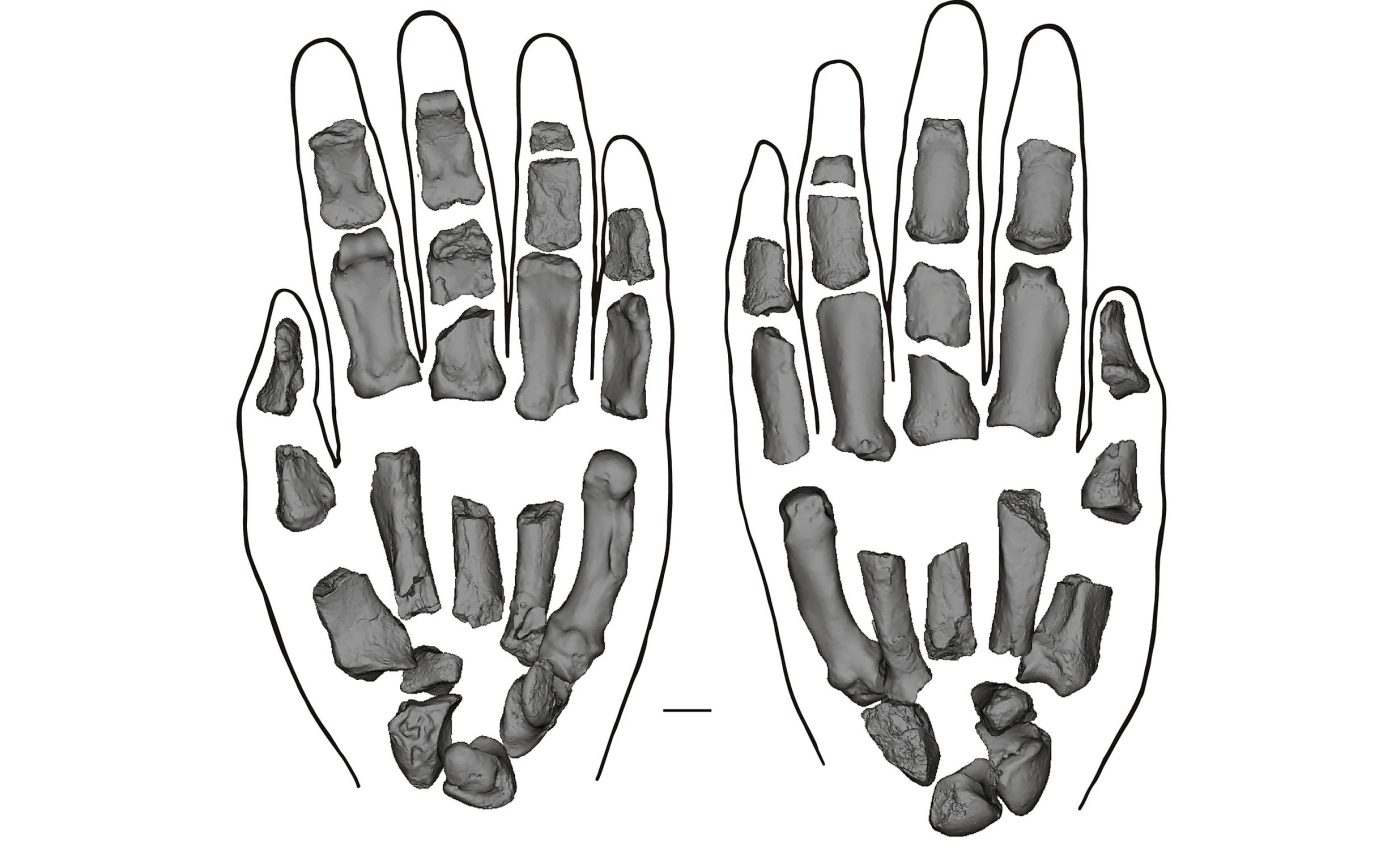

The fossil find includes most of one hand, parts of a foot, teeth, a forearm fragment, and skull pieces from one individual.

Lead author Carrie S. Mongle from Stony Brook University (SBU), led the analysis. Her team coordinated field and lab work across Kenyan and U.S. partners.

Paranthropus boisei had good teeth

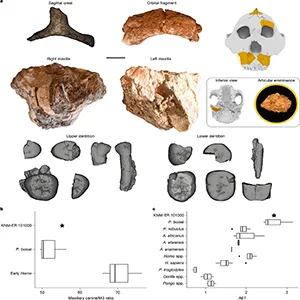

The team tied the fossil hand and foot bones to the skull and teeth by shared traits. One important marker was enamel thickness which matched classic Paranthropus boisei values.

Tooth proportions also lined up with the species; it has small canines and massive molars.

A pronounced sagittal crest on a skull fragment – a ridge for attaching jaw muscles – also pointed to a powerful chewer.

Hands and feet, finesse and force

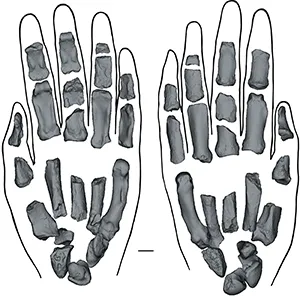

The thumb is long and sturdy, and the little finger is extra strong. That mix of fossil hand bones supports a precision grip while keeping a strong, clenched grasp.

“This is the first time we can confidently link Paranthropus boisei to specific hand and foot bones,” said Mongle. The quote captures why a well-matched hand and foot changes what can be tested.

The palm bones and wrist show a split personality. Some joints look more like those of great apes, while the finger and thumb proportions look very human.

The big toe’s base tilts in a way that helps with push off during walking. A high transverse arch in the mid-foot adds stiffness, which supports a strong step on two legs.

These traits fit with a committed bipedal gait, and walking upright on the ground most of the time. They also hint that climbing stayed possible but was not the main way this animal got around.

Paranthropus boisei had skills

Simple stone tools appeared well before the arrival of our own genus. The Lomekwi site preserves 3.3-million-year-old tools showing early knapping, long before Homo.

On Kenya’s Homa Peninsula, artifacts from the Oldowan turned up next to large Paranthropus boisei teeth. Those findings place clear tool use in East Africa by 3 million years ago.

Taken together with the new understanding of hand structure, these records lower the odds that only Homo made and used early tools. They point to overlapping skills among several lineages in the Pleistocene.

What this means for early diets

Stable isotope work shows that this species ate mostly grasses and sedges. One analysis found heavy use of C4 grasses, which are warm climate grasses with a distinct signature.

Gorilla-like features in the fossil hand’s outer side hint at strong grips used to strip, crush, or peel tough plants.

That pattern matches a specialist plant eater that still had the ability to shape and apply simple stone edges when needed.

Many questions remain

The wrist of the new fossil retains some non-modern features. The carpal region – the small bones of the wrist – lacks several refinements that help later humans pinch with high efficiency.

That leaves room for debate about how often this species actually made tools. It could probably manage basic knapping and cutting, but it may not have relied on tools as heavily as later members of our genus.

Rethinking Paranthropus boisei

At mixed fossil sites, tools have often been assigned to Homo by default. These bones, plus the Kenya tool records, make that habit less safe.

“Before this find, scientists were limited to the cranial and dental remains of this species,” said Louise Leakey from the Koobi Fora Research Project (KFRP).

This explains why a well-matched fossil hand and foot shifts how dig teams label finds at shared sites.

A stronger fifth ray and a robust thumb suggest repeated power grips. Those traits could reflect heavy manual food processing in open habitats where coarse plants were common.

Early tool use now looks less like a single line and more like a shared playbook. Several branches could pick up a stone, reduce a core, and use a sharp edge when the moment called for it.

The study is published in the journal Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–