Scientists are experimenting with a completely new approach to combat human aging

For hundreds of years, humans have pursued the secrets of aging with unwavering determination – decoding our DNA, analyzing free radicals, and testing so-called miracle compounds – in hopes of slowing, halting, or even reversing the passage of time.

Scientists have explored everything from calorie restriction to gene editing, employing strategies as ambitious as they are diverse. Yet aging has continued its steady, unyielding course.

Now, researchers are taking a bold new direction. Instead of focusing solely on how we live, they’re investigating how we die.

They’re zeroing in on something called “necrosis” – a violent, uncontrolled form of cell death once seen as nothing more than biological wreckage – and uncovering its surprising potential to reshape how we understand disease, degeneration, and the future of human longevity.

Necrosis disrupts healthy cell function

Cells typically renew themselves through controlled processes. This renewal helps replace old cells and keep tissues functional.

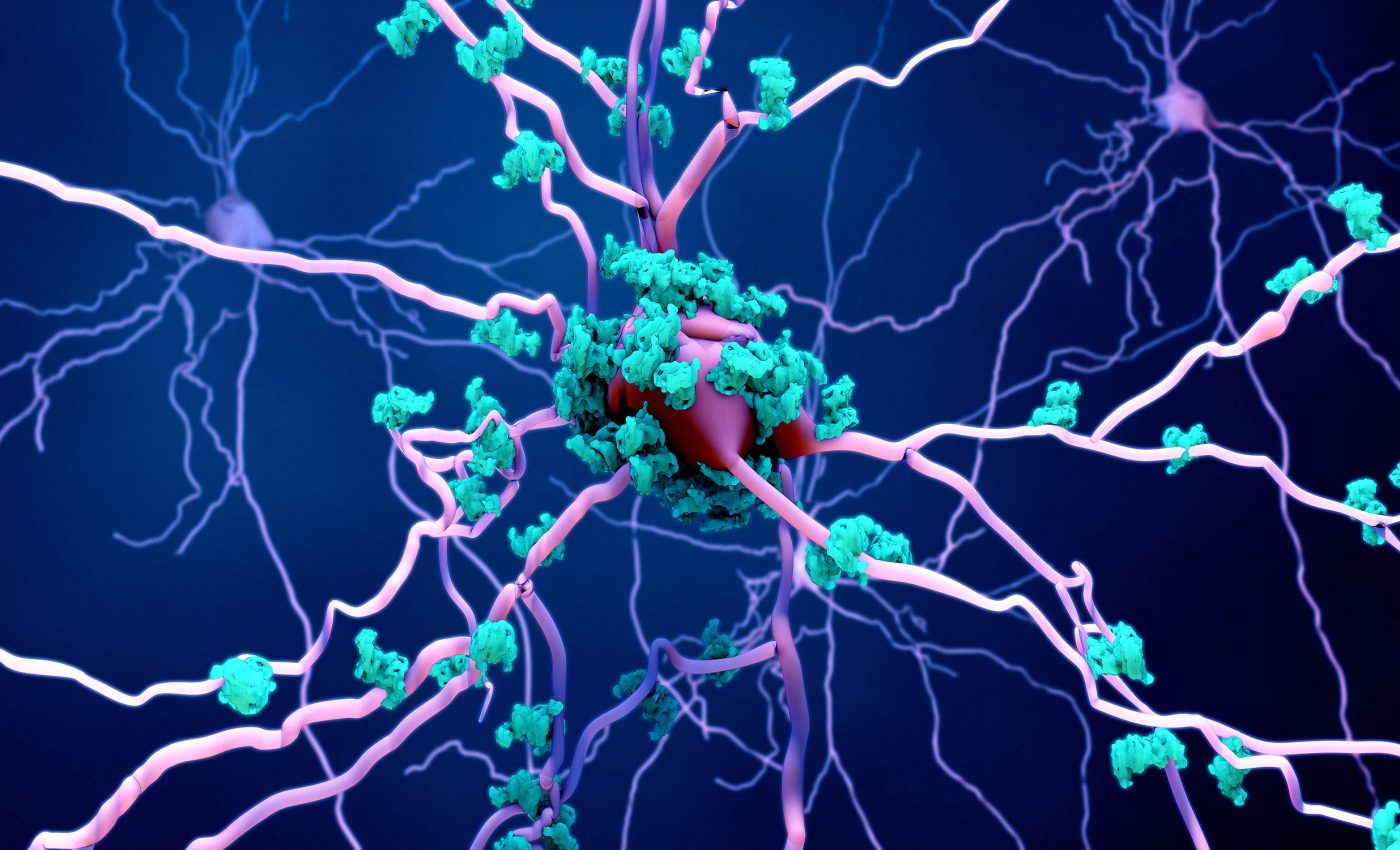

Necrosis occurs when cells die in an abrupt, uncontrolled manner, usually in response to injury, infection, or severe stress.

Unlike apoptosis, the body’s carefully programmed process of cell death, necrosis unleashes chaos. The cell swells, ruptures, and spills its contents into surrounding tissue, triggering inflammation and damaging nearby cells.

This destructive cascade often leads to chronic disease and tissue degeneration, especially when the body cannot repair the affected area.

A global team of scientists looked at the role necrosis plays in many age-related conditions.

“Nobody really likes talking about death, even cell death, which is perhaps why the physiology of death is so poorly understood,” noted Dr. Keith Siew, one of the study’s authors, hailing from UCL Centre for Kidney & Bladder Health.

Kidney, heart, and brain diseases

Kidney problems affect many people in their later years. This organ filters toxins, and when enough kidney cells die, there is a higher chance of needing dialysis.

If necrosis is a major factor in triggering kidney damage, then targeting it might keep kidneys healthier for a longer time.

Research shows that by 75 years old, nearly half of all individuals may experience some level of kidney disease.

Studies also suggest that necrosis may play a part in conditions like heart disease and Alzheimer’s. When cellular breakdown releases harmful molecules, surrounding tissues can become inflamed.

As these tissues struggle, the effects may ripple through the body. Even mild inflammation can wear down the body’s ability to repair itself.

Astronauts and necrosis

Space health experts find necrosis interesting because low gravity and cosmic radiation can strain human organs. Astronauts experience accelerated aging during long missions.

Kidneys are especially vulnerable because reduced fluid regulation and radiation exposure may affect how well they function.

The idea that interrupting necrosis could protect these vital organs has sparked new questions about maintaining astronaut health for extended journeys.

“Targeting necrosis offers potential to not only transform longevity on Earth but also push the frontiers of space exploration,” said Professor Damian Bailey, from the University of South Wales and the European Space Agency Life Sciences Working Group.

Stopping necrosis may protect cells

“If we could prevent necrosis, even temporarily, we would be shutting down these destructive cycles at their source,” said Dr. Carina Kern, CEO of LinkGevity.

Some researchers believe that if necrosis can be paused, it might stop a domino effect of tissue damage. By preserving cells that are on the brink of failure, the body would have a better chance to carry out self-repair.

One hypothesis suggests that keeping calcium levels under control within cells could be essential.

Calcium often acts as a switch, turning on or off important cellular functions. If too much enters a stressed cell, that cell can rupture. Scientists hope that preventing this surge might halt large-scale tissue breakdown.

Improving quality of life

Age-related disorders come with gradual but significant loss of function. Necrosis appears in conditions affecting not just the kidneys but also the brain, heart, and other organs.

When cells burst and release debris, surrounding tissues may endure ongoing inflammation. Interrupting this pattern could reduce suffering and add productive years for many individuals.

This approach might also allow doctors to address multiple health problems at once. Rather than chasing each disease individually, limiting necrosis may let the body maintain its own equilibrium.

As the population grows older, ideas like these could open up new possibilities for health management and medical innovation.

Blocking harmful cell death

Researchers around the world are investigating whether necrosis-blocking drugs or gene-based therapies can be used safely.

They aim to determine if these approaches can work without disturbing beneficial types of cell death that clear out defective or excess cells.

Untangling these processes could be tricky, but the concept of sparing healthy tissues and preventing irreversible damage has captured wide attention.

With more teams studying these pathways, the prospects for harnessing necrosis control are expanding. For now, public interest and continued clinical trials may help clarify how this form of cell death can be targeted effectively.

—–

Special thanks to clinicians from the UCL Division of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Mayo Clinic, and the European Space Agency.

The study is published in Oncogene.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–