Small changes to land use and diet could save thousands of animal species

Behind your morning coffee, afternoon snack, or your next steak dinner lies an invisible chain of life and loss. Farms grow, forests fall, and species vanish.

Scientists at the University of Cambridge have now traced this connection with striking precision.

The new study exposes how food production influences extinction risks across the planet, and how small shifts in what we eat could decide which species endure.

Diets drive biodiversity decline

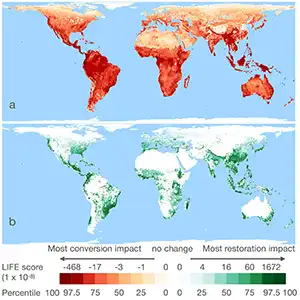

The researchers combined global food data with a biodiversity model called LIFE, short for Land-cover change Impacts on Future Extinctions.

The model tracks how changes in land use affect more than 30,000 species. The results were sobering. Producing 2.2 pounds (one kilogram) of food can vary in its impact on biodiversity by up to a thousand times.

Animal-based foods were by far the most damaging. Ruminant meat such as beef or lamb had a median extinction impact 340 times higher than grains and around 100 times greater than beans or lentils.

“Every time anyone eats anything, it has an impact on the other species we share the planet with,” said Dr. Thomas Ball, the study’s first author.

“Rearing the cattle for one kilo of beef needs a huge amount of land, which displaces a lot of natural habitat. On average, that has a much bigger impact on species’ survival than growing one kilo of vegetable protein like beans or lentils.”

Meat’s massive ecological cost

Agriculture already occupies nearly one-third of Earth’s surface. Over three-quarters of that space exists to produce animal products. Yet these foods provide just 17 percent of the world’s calories. The imbalance is massive.

Crops like grains, roots, and vegetables feed more people while using far less land. Sugar beet, grown mostly in cooler regions, turned out to have one of the smallest extinction impacts per pound because of its high yield and limited effect on wildlife.

Tropical crops told a different story. More coffee, cocoa, tea, and bananas in our diets – grown in biodiversity-rich regions – had far greater effects on species loss.

Even small clearings in rainforests or tropical mountains erase habitats for creatures that live nowhere else. In short, location magnifies damage.

Imports extend extinction footprints

The team examined six countries: the United States, Japan, the United Kingdom, Brazil, Uganda, and India. Each showed a unique pattern of food-related harm.

In Japan and the United Kingdom, most of the extinction footprint came from imported food. Up to 95 percent of their biodiversity impact occurs overseas. Beef and lamb from Australia and New Zealand, along with soy grown in South America, drive much of it.

Brazil, Uganda, and India told another story. Their biodiversity losses came mainly from local farms. Expanding farmland into natural habitats remains their greatest challenge.

The United States stood in the middle – mostly self-sufficient, but still linked to global biodiversity through imported tropical products like coffee and bananas.

Diet changes save species

The researchers tested what would happen if people in the United States changed how they eat. They compared today’s typical diet with three alternatives: the EAT–Lancet planetary health diet, a vegetarian diet, and a fully plant-based diet.

Cutting ruminant meat from four percent of total calories to just one percent – like in the EAT–Lancet diet – reduced biodiversity harm by nearly three-quarters. Vegetarian and vegan diets went further, cutting it by over half again.

Though these diets increased the use of crops, the overall footprint shrank dramatically because far less land was needed for food.

“Our study shows that eating beans and lentils is 150 times better for biodiversity than eating ruminant meat,” said Ball. “If everyone in the UK switched to a vegetarian diet overnight, we could halve our biodiversity impact.”

Smarter farming, safer species

Diet choices are personal, but their impact on species reaches a global scale. Nearly a third of Earth’s land has been transformed for farming in the last sixty years.

Without change, that number will keep rising. The LIFE metric developed at Cambridge now helps governments gauge the global effect of their food imports and policies.

Dr. Ball warned against short-sighted decisions. “We have a UK agricultural policy that incentivizes farmers to set aside more land for nature, and reduce food production.”

“But if that means we’re making up the shortfall by relying on imports from more biodiverse places, it could cause far more damage to the species on our planet in the long run.”

Choosing balance on our plates

The study urges a mix of solutions. Sustainable high-yield farming can meet human needs while protecting untouched ecosystems.

Smarter trade policies can reduce the harm of imports. And individuals can help by choosing foods that demand less land and fewer animal products.

Agriculture will always shape nature. But now, for the first time, scientists can measure how much each diet affects species.

The message is clear: we can choose a meal that feeds people without pushing species toward extinction. The choice sits right on our plates.

The study is published in the journal Nature Food.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–