Smoking leaves permanent traces in teeth deep below the surface - a new forensic

Scientists recently discovered that certain changes in the roots of teeth can reveal whether someone is a current or former smoker.

This breakthrough came from a team at Northumbria University, working alongside scientists from the University of Leicester. Their findings could offer powerful tools for both forensic science and archaeology.

What teeth can tell us

Your teeth aren’t just for chewing. They carry a hidden timeline of your life. Teeth are made up of enamel, dentine, and cementum.

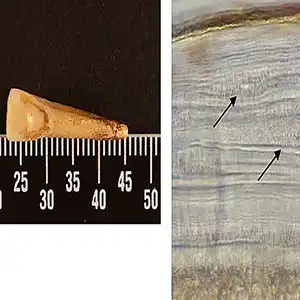

Cementum is the hard tissue that coats the tooth’s root, and it grows in layers – similar to the way trees deposit annual growth rings. Every year, a new layer forms.

The research team originally set out to use these cementum rings to estimate a person’s age. That kind of analysis can help identify victims of disasters when DNA samples aren’t available.

“By looking at growth rings in the teeth, we can also estimate a person’s age when the tooth was removed, or when they died,” said Dr. Ed Schwalbe, coauthor and professor in the Faculty of Health and Life Sciences at Northumbria University.

“Together, this information could help identify unknown individuals – such as disaster victims or those buried in mass graves – and offer new tools for forensic and historical investigations,” he confirmed.

But they also found something unexpected.

Smoking marks teeth as well

They examined 88 teeth from both living dental patients and archaeological remains. In many cases, the cementum rings weren’t smooth and regular. Some had disruptions – changes in thickness or shape that didn’t line up with the typical growth pattern.

They looked more closely. These disruptions weren’t random. They were consistently found in the teeth of people who smoked or used to smoke.

“Our research shows that it’s possible to tell if someone was a smoker just by examining their teeth,” said Dr. Schwalbe.

“We found that the regular annual deposition of rings was disrupted for some individuals and realised that these disruptions were associated with current or ex-smokers, but were very rare in non-smokers.”

Smoking’s undeniable signature in teeth

In teeth from former smokers, the team saw thick layers of cementum built up over disrupted rings. They believe that when someone quits smoking, the cementum begins to return to a normal growth pattern, forming denser layers on top of the older, damaged ones.

That may explain why ex-smokers’ teeth showed thicker cementum than was found in the teeth of current smokers.

The numbers were striking. Disrupted cementum appeared in 70% of ex-smokers and 33% of current smokers – but in only 3% of people who had never smoked.

“We compared the cemental deposition of smokers, ex-smokers and non-smokers visually and statistically to identify irregularities that were potentially connected to smoking activity,” said Dr. Valentina Perrone, lead author on the study.

“We found that individuals with a history of smoking – whether as a current or former smoker – were significantly more likely to have disruption to their cementum than those who did not.”

Quitting doesn’t remove smoking markers

The study included 46 living participants who needed teeth extracted as part of routine dental care. In one standout case, a participant’s tooth showed damage estimated to have occurred between the ages of 22 and 41.

When the researchers reviewed the patient’s history, they found that the individual, who was aged 58 at the time, had smoked between the ages of 28 and 38.

That matched the evidence exactly.

“Smoking is known to have a systemic impact on the body and numerous studies have highlighted the correlation between smoking, periodontitis and tooth loss,” Dr Perrone added.

“This study shows, for the first time, the biological record of smoking-related oral health damage within the dental structure.”

Echoes from past centuries

To test whether these markers of smoking could be found in much older remains, the team worked with Dr. Sarah Inskip, UKRI Fellow at the University of Leicester’s School of Archaeology and Ancient History. They examined 18 archaeological teeth dating from between 1776 and 1890.

Some of these teeth came from individuals known to have smoked. Signs included discoloration and even physical notches worn into the teeth by clay pipes.

Even after centuries underground, the cementum in those teeth still bore the same disruption patterns as found in the teeth of modern smokers.

“This could help us learn more about people’s lifestyles in the past, especially in archaeological studies where patterns of tobacco use can reveal important cultural insights,” said Dr. Schwalbe.

“The identification of ‘smoking damage’ in archaeological teeth opens up further avenues to understand how the long-term consumption of tobacco in populations has affected our health through time,” Dr. Inskip added.

Your teeth don’t lie

These findings show that even if someone quits smoking, their teeth may carry the evidence for life.

That insight has major implications – not just for understanding personal health histories, but for reconstructing the lives of people long gone.

The next time you smile, remember that your teeth are holding a history of some of your lifestyle choices.

The full study was published in the journal PLOS One.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–