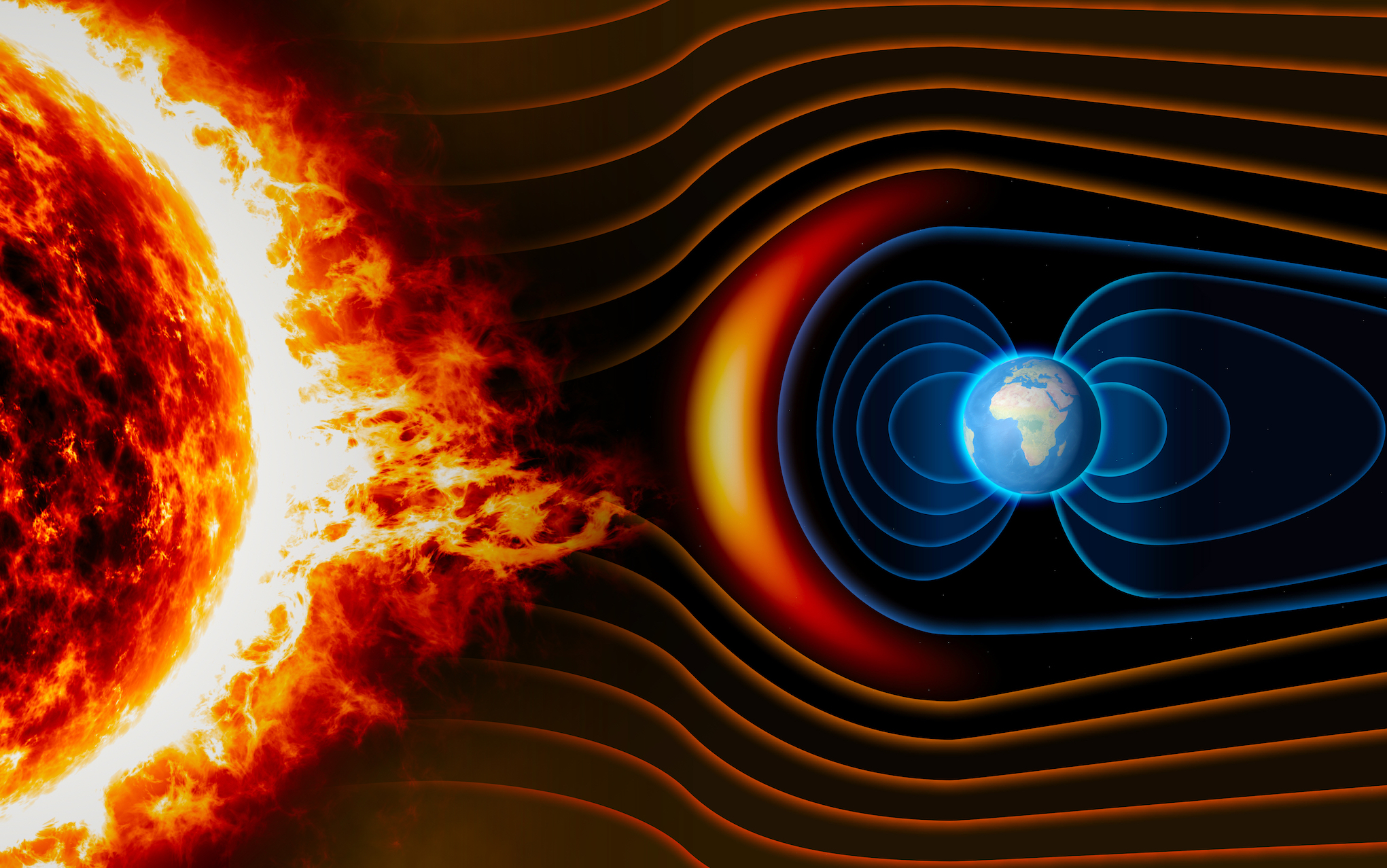

When solar wind collides with Earth’s magnetic field

The NASA spacecraft mission Magnetospheric Multiscale (MMS) has revealed what happens to the turbulent energy that is created when solar wind collides with the Earth’s magnetic field. The energy forms into high-speed electron jets as the moving electric charge breaks down and reconnects.

This type of magnetic reconnection occurs throughout the universe, and understanding the process as it relates to the Earth could help scientists better understand other processes in outer space.

“Turbulence occurs everywhere in space: on the sun, in the solar wind, interstellar medium, dynamos, accretion disks around stars, in active galactic nuclei jets, supernova remnant shocks and more,” explained study co-author Michael Shay.

Study lead author Tai Phan is a senior fellow in the Space Sciences Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley.

“MMS discovered electron magnetic reconnection, a new process much different from the standard magnetic reconnection that happens in calmer areas around Earth,” said Phan. “This finding helps scientists understand how turbulent magnetic fields dissipate energy throughout the cosmos.”

Standard magnetic reconnection is observed in Earth’s magnetosphere, but electron magnetic reconnection takes place much farther away in a highly turbulent zone called the magnetosheath. This is where solar wind hits like a shock wave and surrounds the planet.

“The turbulence in the magnetosheath contains a lot of magnetic energy,” said Phan. “People have been debating how this energy is dissipated, and magnetic reconnection is one of the possible processes.”

Using data from MMS, the research team observed electron magnetic reconnection for the first time, and determined that the process creates electron jets instead of the ion jets that are generated by standard magnetic reconnection.

“We now have evidence that reconnection does happen to dissipate turbulent energy in the magnetosheath, but it is a new kind of reconnection,” said Shay.

According to Phan, it was unknown prior to this study if magnetic reconnection could take place in the magnetosphere because the plasma is highly chaotic in that region.

The activity detailed by MMS had been previously overlooked by scientists who were looking for ion jets instead of electrons, which move about 40 times faster than ions accelerated by standard reconnection.

MMS instruments were not fast enough to capture the turbulent reconnection, but the experts managed to detect the process by developing a technique of combining separate data points.

Amy Rager worked at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center to develop the technique.

“The key event of the paper happens in 45 milliseconds. This would be one data point with the regular data,” said Rager. “But instead we can get six to seven data points in that region with this method, allowing us to understand what is happening.”

The scientists are hopeful that more surprising events will be discovered in existing datasets using their new method.

The research is published in the journal Nature.

—

By Chrissy Sexton, Earth.com Staff Writer