Humans butchered elephants then made large tools from their bones 400,000 years ago

Archaeologists working on the outskirts of Rome have discovered a Middle Pleistocene elephant butchery site where small stone flakes did most of the cutting, and the mammal’s bones became heavy-duty tools.

The study dates the event to about 404,000 years ago.

The Pleistocene was the long Ice Age period that ended about 11,700 years ago. This find sits in that era’s warm spell and captures a short episode of people processing a single straight-tusked elephant.

Elephant bones and primitive tools

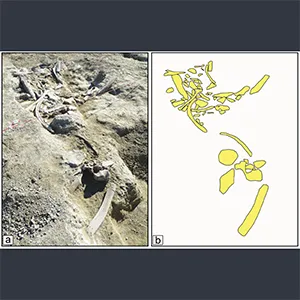

The work was led by Beniamino Mecozzi of Sapienza University of Rome. His team mapped a single elephant carcass, identified as Palaeoloxodon antiquus, an extinct species of the large straight-tusked elephant, and the tools left around it.

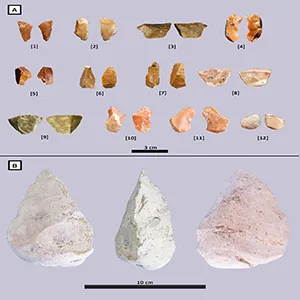

They recovered over 300 bones from the same mammal alongside more than 500 stone artifacts. Many cutting tools were smaller than 1.2 inches.

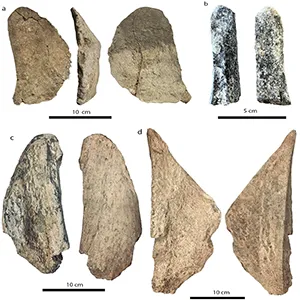

Several elephant bones were reshaped into larger implements, and a single hand-axe turned up about 49 feet from the main carcass concentration.

Dating places the event in Marine Isotope Stage 11 (MIS 11), a notably warm interglacial that altered rainfall and vegetation across many regions.

Warmer conditions and stable water sources likely made large animals more predictable in the landscape.

Layers of volcanic ash and rock particles ejected by eruptions at the site, along with ash chemistry, anchor the age and tie it to known eruptions in central Italy.

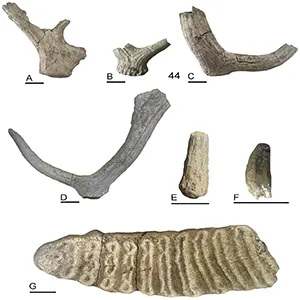

Tooth enamel isotopes from the elephant point to humid, wooded habitats that track with the local river system.

Scientists use the label MIS 11 for this slice of time, and in central Italy, it lined up with wooded riparian settings rather than arid grassland.

That environmental picture fits the fauna found with the elephant and the way the remains settled in a shallow channel.

Butchering elephants with tiny tools

Experimental and archaeological research shows that tiny flakes can slice meat and fat efficiently, especially when precision cuts matter. Small edges bite cleanly into soft tissue and leave fewer deep marks on bone.

At Casal Lumbroso, the toolset is a classic lithic (stone-based) kit made mostly from local pebbles.

Ancient knappers split small cores using a hammerstone, then placed a pebble on a stone base, and struck from above to pop off thin, sharp flakes.

Thick, soft tissue around an elephant skeleton means bone surfaces are not always touched by blades.

Fewer cut marks should not be read as no butchery, especially when the toolkit slice is small and the elephant’s soft tissues are very thick.

Heavy-duty tools from elephant bones

When stones run small, bone can fill the gap for heavy tasks that need leverage, reach, or impact.

Systematic evidence, from the nearby site of Castel di Guido, shows standardized tools made from elephant limb fragments and a clear workflow for producing them.

At La Polledrara di Cecanibbio, butchery traces, fractured long bones, and reused elephant parts connect carcass processing with osseous, or bone-based, toolmaking.

That record demonstrates marrow extraction alongside shaping of bone blanks. Casal Lumbroso adds 16 elephant bones with fresh fracture edges and localized wear at their tips.

One rib fragment used as a tool measures about 30 inches long, far larger than most of the stone pieces recovered at the same level.

Archaeologists confirm findings

Investigators combined careful mapping, microscopic inspection, and sediment chemistry to build the sequence of events.

The team applied taphonomy, the branch of archaeology that studies how living things decay and become fossilized, to distinguish human activity from water movement or carnivore damage.

Ash geochemistry tied the layers to known eruptions and set a tight window for the site’s age. Isotope readings, chemical signatures used to infer environmental conditions, from the elephant’s tooth tracked seasonal swings in water and plants over roughly two years of tooth growth.

Use wear on edges told a consistent story of scraping and cutting soft to medium soft materials. That pattern fits a butchery episode focused first on soft tissues, then on targeted bone breakage for marrow and tool blanks.

Elephants and tool patterns

What happened on this streambed near Rome does not stand alone. A detailed paper on Marathousa 1 in Greece describes a similarly focused elephant butchery event in a lakeside setting, reinforcing how often large carcasses drew people to water.

Across Latium, sites show small pebble-based industries paired with occasional handaxes and frequent bone tools. That toolkit mix points to flexible choices under raw material limits, without any loss of cutting performance.

Taken together, the Italian record shows a late Acheulean strategy tuned to place and season. People used small flakes for precision, bone for force, and moved on when the work was done.

Ancient way of life

This site makes early European behavior feel practical and hands-on rather than mysterious. It ties tool choice to raw material size, carcass physics, and the realities of a warm interglacial landscape.

“Reconstructing these events means bringing to life ancient and vanished scenarios, revealing a world where humans, animals, and ecosystems interacted in ways that still surprise and fascinate us today,” said Mecozzi.

The record in the ground shows careful planning, not just opportunism.

The study is published in PLOS One.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–