Stone tools over 1 million years old were made by an unknown human ancestor

The discovery of seven stone tools at Calio on the island of Sulawesi has changed our understanding of early hominin movement across Southeast Asia.

Researchers from Griffith University dated the tools at 1.04 million years old, which suggests that Sulawesi was populated far earlier than was previously believed.

Previous excavations on Sulawesi had revealed stone tools that were dated to around 194,000 years ago, making this latest discovery the earliest direct evidence of hominin presence by far.

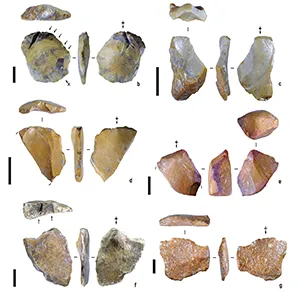

In the Early Pleistocene, Calio was a riverside area where tool-making likely took place. The latest tools consisted of seven stone flakes that were crafted from chert, suggesting that early hominins actively selected this material.

Sulawesi rocks locked in time

Calio lies in South Sulawesi’s Walanae Depression, which was formed by tectonic collisions. The tools were recovered from sandstone layers of the Beru Member Sub-Unit B.

This layer belongs to the broader Walanae Formation, known for its river-deposited sediments and rich fossil record.

The Calio excavation revealed complex layering of river-deposited sandstones, conglomerates, and gravel beds.

Among these were the bones of extinct animals, including a maxilla from a suid called Celebochoerus heekereni. This specimen helped confirm the site’s age.

Tools are over a million years old

The research team used two powerful dating methods: paleomagnetic analysis and US-ESR dating. Magnetic signals from the sediments showed reversed polarity, giving the tools a minimum age of 773,000 years.

US-ESR dating of fossilized teeth yielded ages between 1.20 and 1.43 million years. This provides a minimum age of 1.04 million years for the stone tools, and possibly as early as 1.48 million years.

The consistency between the results obtained using these methods strengthens the case.

Early tools show real skill

These early tools were not crude. The flakes were struck using hard-hammer freehand percussion. Many show signs of skilled reduction techniques, such as platform rotation and flake-on-flake knapping.

One tool, a Kombewa flake, shows evidence of deliberate retouching along its edge. All tools were made from river-sourced chert and showed signs of expert craftsmanship.

Their larger average size compared to surrounding unmodified pebbles confirms deliberate selection and transport of raw material by the early toolmakers.

Humans crossed the sea to Sulawesi

“This discovery adds to our understanding of the movement of extinct humans across the Wallace Line, a transitional zone beyond which unique and often quite peculiar animal species evolved in isolation,” said Professor Adam Brumm of Griffith University.

This crossing required a major ocean voyage. It suggests hominins, possibly Homo erectus – reached islands like Flores, Sulawesi, and Luzon without any land bridges.

Evidence from Luzon and Flores aligns with these findings, but Calio now provides the earliest known date for Wallacean hominin activity.

“It’s a significant piece of the puzzle, but the Calio site has yet to yield any hominin fossils; so while we now know there were toolmakers on Sulawesi a million years ago, their identity remains a mystery,” said Brumm.

Homo floresiensis, found on nearby Flores, is a possible clue. That species may have descended from Homo erectus that reached the island and later became smaller in size due to island isolation. Whether the same happened on Sulawesi remains an open question.

Island life shaped evolution

“Sulawesi is a wild card – it’s like a mini-continent in itself,” said Brumm.

“If hominins were cut off on this huge and ecologically rich island for a million years, would they have undergone the same evolutionary changes as the Flores hobbits? Or would something totally different have happened?”

With Sulawesi being over 12 times larger than Flores, evolutionary outcomes may have diverged. The island’s scale, diversity, and isolation make it an exciting focus for future research.

Sulawesi tool discovery rewrites history

The tools at Calio reveal a chapter of human migration that is not just older, but more complex than we imagined.

These findings don’t just place hominins on Sulawesi over a million years ago – they also highlight their adaptability, tool-making skills, and capacity for long-distance sea travel.

What happened after they arrived? Did they thrive, evolve, or vanish without a trace? We don’t yet know. But each stone flake tells us they were there – getting on with the business of survival.

The study is published in the journal Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–