Study shows that early humans climbed trees and worked with stone

Early human ancestors sometimes left hints of daily life in their bones. Researchers have analyzed fossil hands from southern Africa and discovered that these ancient populations relied on climbing as well as handling stones for possible tool-related tasks.

They studied the species Australopithecus sediba from around 2 million years ago and Homo naledi from around 300,000 years ago.

Study co-author and paleoanthropologist Samar Syeda of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) explained that skeletal measurements indicate fingers were once under a variety of stresses from climbing and other movements.

Early human tree climbing

Researchers found that bones from early humans thickened in areas associated with powerful grasping, which points to moments spent hanging on tree limbs or supporting body weight.

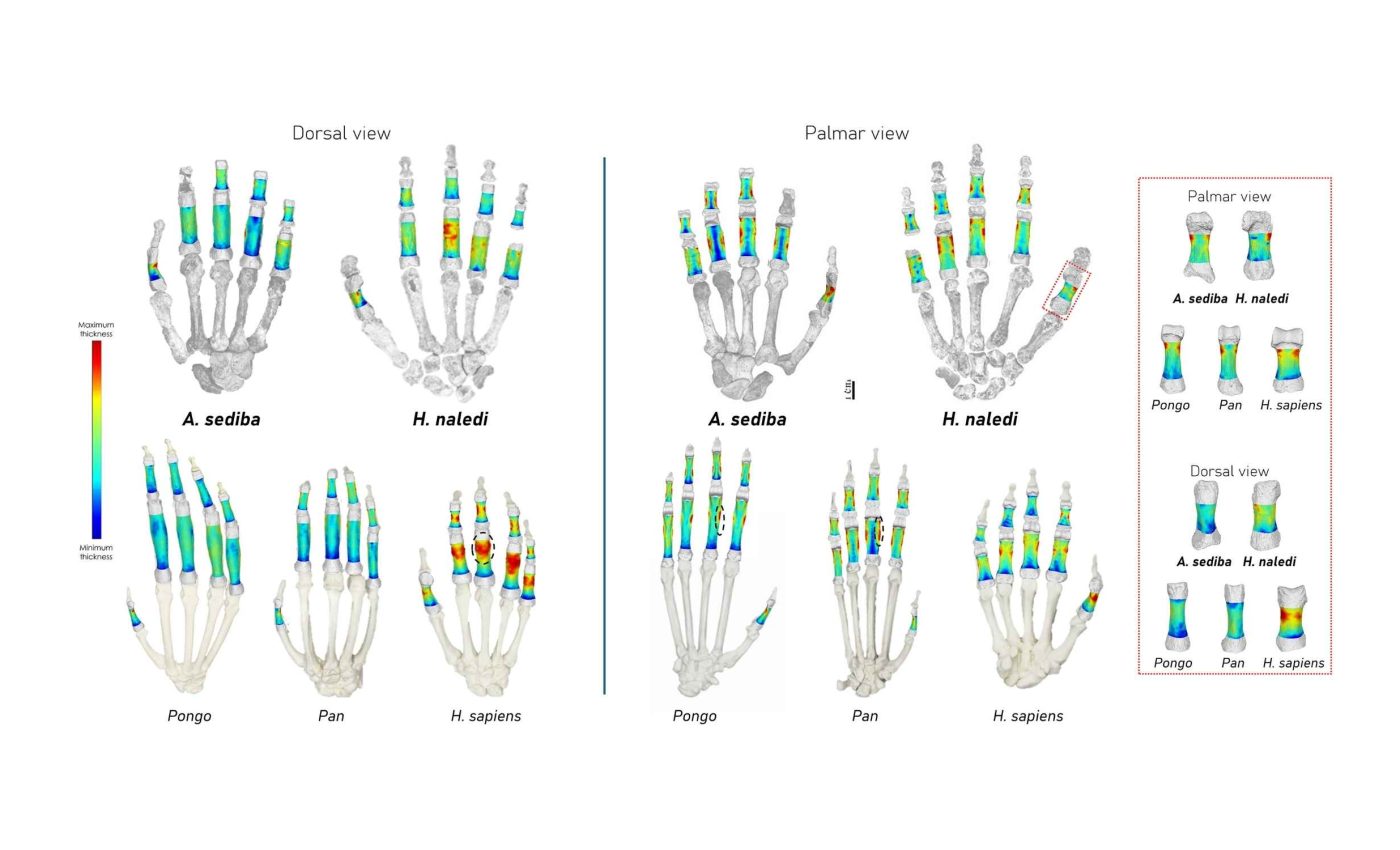

They used advanced 3D scanning to assess how different parts of each finger responded to stress, and the results suggest repeated pressure from climbing.

“They were likely walking on two feet and using their hands to manipulate objects or tools, but also spent time climbing and hanging, perhaps on trees or cliffs,” said Samar Syeda.

Scientists also described the curved shape of certain finger bones. That curvature is commonly tied to supporting the body during upward movements, hinting at a habit that wasn’t purely about walking or running.

Early humans, trees, and tools

Another part of this project looked at how the thumb and little finger might have played a role in tool-related grip.

Researchers found signs of bone thickening in places that would assist in pressing or gripping stones, which strengthens the idea that these species were not just scanning the trees for fruit.

“The findings show there wasn’t a simple ‘evolution in hand function where you start off with more ‘ape-like’ and end up more ‘human-like,’” explained Smithsonian paleoanthropologist Rick Potts, who was not involved in the study.

This observation implies that hand use in ancient populations didn’t transition in one straight line. Instead, early humans found ways to keep climbing while also beginning to shape or handle stones.

Tool use and human origins

The presence of a powerful thumb in H. naledi catches attention. Scientists note that thick bone along the thumb could help with forceful pinching or pressing against objects.

Investigations of A. sediba revealed a similar pattern in the fifth digit, though less robust. That difference reminds us that individuals may have adopted separate approaches to day-to-day chores.

“Hands are one of the primary ways we engage with world around us,” said Chatham University paleontologist Erin Marie Williams-Hatala.

It’s likely that working with stones, whether for cutting or breaking open food, shaped how these fingers developed internally.

The careful analysis of finger bones matched previous studies on primates that climb. In modern contexts, climbers often generate high stress on the palms and mid-digits, leading to thicker bone in those spots.

Early human finger bones and trees

Finger bones, especially the middle sections called phalanges, are particularly good at recording how hands were used.

Because bone remodels over time in response to pressure, areas under more frequent or intense stress get thicker. That remodeling can serve as a long-term record of climbing, hanging, or pressing behaviors.

In the case of these early human relatives, the variation in cortical bone thickness across the palm and back of the fingers told researchers where pressure was being applied most often.

These tiny clues helped determine which fingers bore the brunt of hanging from branches versus which ones may have pinched or pressed objects with force.

Ongoing questions about ancestors

One question is how different these early humans were from other hominin groups. They probably stood on two feet for tasks on the ground, yet their hands still took on climbing duties.

That flexibility gave them a wide range of motion for reaching high branches or clutching stones.

Scientists suggest that these fossils show hand evolution wasn’t always linear. Some groups kept a mix of older traits while developing improved grip for sophisticated tasks. This blend of features signals a dynamic lifestyle.

Bone data also highlight the idea that each species handled the environment on its own terms. The interplay of thickened bone for climbing and potential stone work reveals surprising layers in the story of human origins.

Not all hands evolved the same way

The internal structure of the fingers in A. sediba and H. naledi shows that different species may have developed their own strategies for using their hands.

While both still climbed, their gripping styles and tool-handling strengths were not identical. That difference challenges the idea of a single path toward modern human dexterity.

Researchers suggest that instead of one shared route, hand evolution branched in several directions depending on the environment and behavior.

Some species prioritized strength for climbing, while others leaned more into thumb-powered precision. This variety suggests early humans were adapting in ways that were more flexible than previously thought.

What this means for modern anatomy

Studying ancient hand bones helps researchers understand why the modern human hand looks and functions the way it does.

Features like a long, strong thumb and relatively straight fingers aren’t just random traits, they reflect a shift away from climbing and toward tasks that require grip precision, like making tools or writing.

Some parts of our hands, like the thick pads under the thumb or the ability to oppose it to each finger, may have developed as climbing declined.

These changes allowed humans to become better at manipulating small objects, shaping tools, and eventually using complex technologies.

The study is published in Science Advances.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–