Super-Earth found just 20 light-years away is our 'best chance so far' to find life

Over the past thirty years, astronomers have identified more than 7,000 planets outside of our solar system – a remarkable leap since the first exoplanet discovery in 1995.

Now, a group of astronomers has confirmed finding a super-Earth that orbits a star very similar to our Sun. The planet circles a star called HD 20794 and sits in a region where liquid water could exist on a rocky surface.

The study appears in Astronomy & Astrophysics and is based on one of the longest planet-hunting data sets, representing a key step in exoplanetology’s ongoing shift from merely detecting planets to investigating their features, particularly conditions that might support life.

Super-Earth HD 20794 d

Oxford University scientist Dr. Michael Cretignier first noticed something unusual in this star’s light while examining archived data from the HARPS spectrograph on the 3.6-meter telescope at the La Silla Observatory in Chile. In 2022, he saw a regular pattern in the star’s radial velocity.

The signal was very faint, so it was not clear whether it came from a planet, from activity in the star, or from an instrumental effect.

An international team re-examined the HARPS observations more recently and added new data from the ESPRESSO spectrograph in Chile to check whether a real planet was present.

“For me, it was naturally a huge joy when we could confirm the planet’s existence,” Dr. Cretignier explained.

“It was also a relief, since the original signal was at the edge of the spectrograph’s detection limit, so it was hard to be completely convinced at that time if the signal was real or not. Excitingly, its proximity with us (only 20 light-years) means there is hope for future space missions to obtain an image of it.”

Two decades of measurements

The team used a post-processing pipeline called YARARA on the HARPS spectra and a tool called sBART on the ESPRESSO spectra to correct for effects from the instruments, Earth’s atmosphere, and the star’s own activity before extracting clean radial velocities.

They then modeled the remaining “stellar noise” with statistical tools called Gaussian processes and removed the effects of magnetic cycles and the star’s rotation from the signal.

“We worked on data analysis for years, gradually analyzing and eliminating all possible sources of contamination,” added Dr. Cretignier.

After that, they compared models with zero to four planets and found that a three-planet model best matched the cleaned data.

Super-earths in this system

A super-Earth is a planet that is larger than Earth but smaller than gas giants like Neptune. The three planets are labeled HD 20794 b, c, and d.

Planet b orbits closest to the star with a period of about 18.3 days and has a minimum mass of 2.15 times that of Earth. Planet c orbits farther out with a period near 89.7 days and has a minimum mass close to 3 Earth masses. Both move on nearly circular paths and fall into the super-Earth class.

HD 20794 d occupies a system that includes two other planets, all revolving around a G-type star (similar to our Sun) at a distance of approximately 19.7 light-years.

Study co-author Xavier Dumusque is a senior lecturer and researcher in the Department of Astronomy at the University of Geneva (UNIGE)

“HD 20794, around which HD 20794 d orbits, is not an ordinary star,” noted Dumusque. “Its luminosity and proximity makes it an ideal candidate for future telescopes whose mission will be to observe the atmospheres of exoplanets directly.”

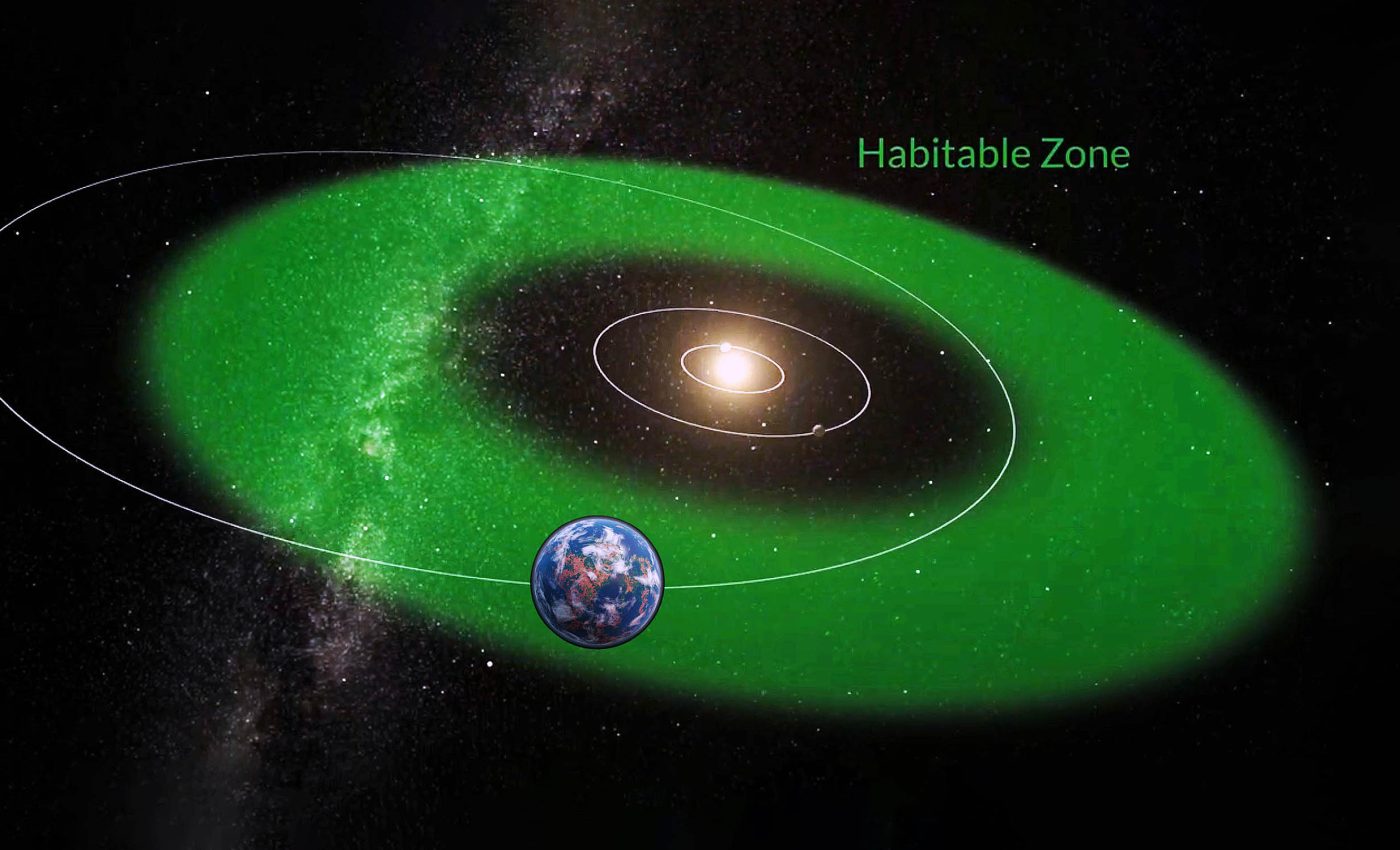

Among the planet’s most intriguing features is its eccentric orbit, causing HD 20794 d to oscillate between the inner edge of its star’s habitable zone at 0.75 astronomical units (AU) and extending outwards to 2 AU.

Such an orbital path could allow for periods in which surface temperatures might be suitable for liquid water, although the planet’s distance from the star varies significantly over the course of its 647-day year.

Future HD 20794 d missions

This result leaves HD 20794 as a nearby Sun-like star with a compact system of low-mass planets, making the system especially interesting for future studies.

Because the host star is easy to observe, HD 20794 d stands out as a key target for future instruments that aim to directly image exoplanets and split their light into spectra.

Extremely large ground-based telescopes and future space missions could, in time, probe this planet’s atmosphere and look for gases linked to geological or even biological activity, while still stopping short of claiming any sign of life.

“While my job mainly consists of finding these unknown worlds, I’m now very enthusiastic to hear what other scientists can tell us about this newly discovered planet, particularly since it is among the closest Earth-analogues we know about and given its peculiar orbit,” Dr. Cretignier concluded.

In the meantime, the Center for Life in the Universe (CVU) at UNIGE’s Faculty of Science is already investigating this planet’s habitability.

The experts are integrating diverse scientific disciplines to explore conditions that might allow life to arise and flourish on exoplanets.

While multiple barriers remain – most notably, the need for more advanced observation techniques and sustained interdisciplinary collaboration – HD 20794 d stands as a powerful reminder of how far exoplanet exploration has progressed.

The study is published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics,

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–