The key to swimming in a school of fish is focusing on neighbors

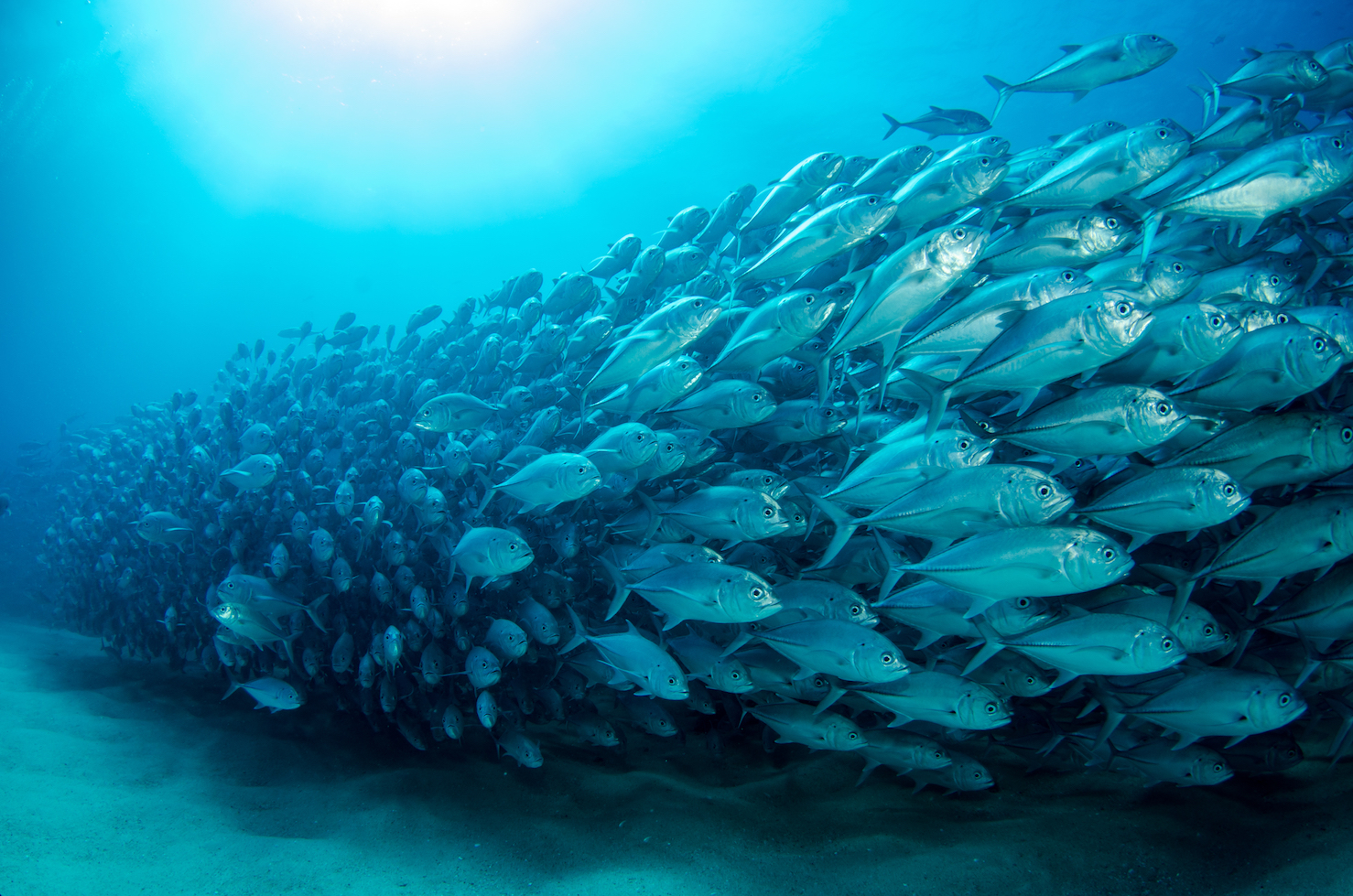

Have you ever noticed how flocks of birds and schools of fish manage to seamlessly change direction despite their size? A new study has shed light on how that group coordination occurs within a school of fish.

The study was conducted by researchers from Beijing Normal University in China and published in the journal PLOS Computational Biology.

According to the researchers, group coordination depends on each fish changing which of its fellow fish it pays attention to. The group movement occurs more seamlessly because each fish alternates which of its neighbors it watches. If a fish is looking at its neighbor and that fish changes direction, then the other fish will change direction as well.

Scientists have been familiar with this neighborly interaction in birds and fish, but this new study examines how many fish need to focus on a single neighbor to move direction.

The tetras were placed in small groups and put in ring-shaped tanks. The size and shape of the tank allowed the researchers to note the directional shifts as either clockwise or counterclockwise.

The researchers were able to then identify which fish were guided by which of their neighbors when the group changed direction.

The study also used a computational model of the directional changes in the groups of fish. This model helped rule out coincidental directional shifts in the group.

The results found that when the group changed direction, it was because one or two neighbors influenced other fish in the group. Group coordination, according to the study, happens because the fish in the group are constantly changing which neighbor fish they pay attention to.

The researchers say this is a necessary survival tactic, as the leader can be determined at any time depending on what threats the group comes across.

“The ability to coordinate movements across a group without a leader confers some advantages, including efficient task partitioning and resilience to loss of a leader,” said Li Jiang, one of the authors of the study. “The rummy-nose tetra appears to have opted for a coordination strategy whereby any individual may become a leader depending on the need.”

—

By Kay Vandette, Earth.com Staff Writer