These tiny creatures play an outsized role in Southern Ocean carbon storage

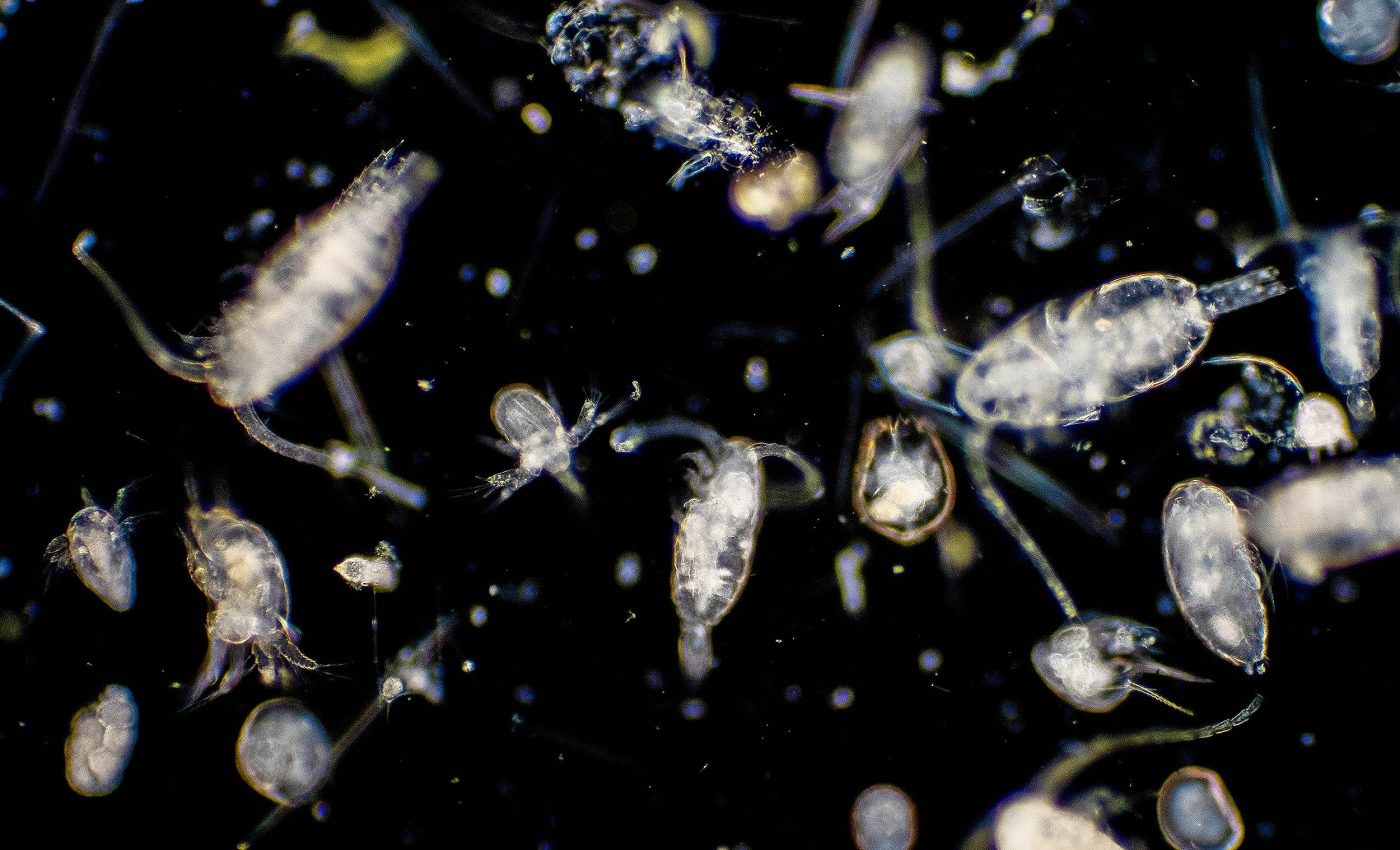

They may be small, but zooplankton like copepods, krill, and salps are pulling serious weight when it comes to storing carbon in the Southern Ocean.

Every year, billions of these tiny animals migrate from the surface to deep waters. In doing so, they help trap tens of millions of tons of carbon far below the ocean surface.

A new look at ocean carbon storage

Until recently, scientists believed most of the carbon stored in the Southern Ocean sank slowly through the water column, tied up in the waste left by larger zooplankton feeding near the surface. But a new study offers a clearer – and more surprising – picture.

The research was led by experts at the Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Plymouth Marine Laboratory, the University of Plymouth, and the British Antarctic Survey

The study is the first to measure how much carbon is pulled down by the “seasonal migrant pump.”

In this process, zooplankton descend each autumn to depths below 1,640 feet (500 meters), stay there for months, and release carbon into the deep ocean through respiration and death.

Tiny swimmers store carbon

The team analyzed thousands of net haul samples collected over the past century from across the Southern Ocean. The records helped build a massive database that tracks how deep and how consistently these creatures migrate each year.

What the researchers found is eye-opening: this seasonal migration injects about 65 million tons of carbon annually into the deep ocean. This enormous amount of carbon could otherwise stay in the atmosphere, contributing to global warming.

“We find that copepods significantly dominate carbon storage overwinter,” said Dr. Jen Freer. “This has big implications as the ocean warms and their habitats may shift.”

Carbon storage in the Southern Ocean

Copepods – small, shrimp-like crustaceans – are the main drivers of this deep-sea carbon delivery system. They’re responsible for about 80 percent of the total carbon flux linked to the seasonal migrant pump. Krill contribute another 14 percent, while salps account for six percent.

These numbers matter. The Southern Ocean absorbs about 40 percent of human-released CO2 that ends up in the oceans.

That’s a huge chunk, but until now, models didn’t factor in this seasonal migration. They focused mostly on passive sinking – when detritus like feces or dead material falls through the water.

Unlike the slow sinking process, the seasonal migrant pump is a direct injection. And it has another upside: it keeps essential nutrients like iron in the upper layers, where they support marine life.

That means zooplankton aren’t just removing carbon – they’re doing it efficiently, without robbing the ocean’s surface of the nutrients needed to keep ecosystems going.

Warming shifts zooplankton paths

The Southern Ocean is changing. Climate warming is shifting the range of species like krill and copepods, and that could reshape how much carbon gets locked away each year.

“The study shows the ‘seasonal migrant pump’ as an important pathway of natural carbon sequestration in polar regions,” said Dr. Katrin Schmidt. “Protecting these migrants and their habitats will help to mitigate climate change.”

The research suggests that climate models are in urgent need of an update. Current Earth System Models don’t include this zooplankton-driven mechanism, which means they may be missing a key part of the ocean’s carbon story.

“This study is the first to estimate the total magnitude of this carbon storage mechanism,” said Professor Angus Atkinson. “It shows the value of large data compilations to get an overview of the relative importance of carbon storage mechanisms.”

Small creatures, global impact

By building on nearly a century of data and contributions from scientists in China, the UK, and Canada, the study provides one of the clearest pictures yet of how small marine animals influence global climate through ocean carbon storage.

“Our work shows that zooplankton are unsung heroes of carbon sequestration,” said study lead author Dr. Guang Yang. “Their seasonal migrations create a massive, previously unquantified carbon flux – one that models must now incorporate.”

Protecting the Southern Ocean means more than safeguarding biodiversity. It means defending one of the planet’s most efficient natural carbon storage systems – powered by creatures smaller than a grain of rice.

The full study was published in the journal Limnology and Oceanography.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–