Why the most distant galaxy ever seen might actually be an impostor

Astronomers examining data from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) say they’ve spotted a contender for the most distant galaxy ever seen, Capotauro.

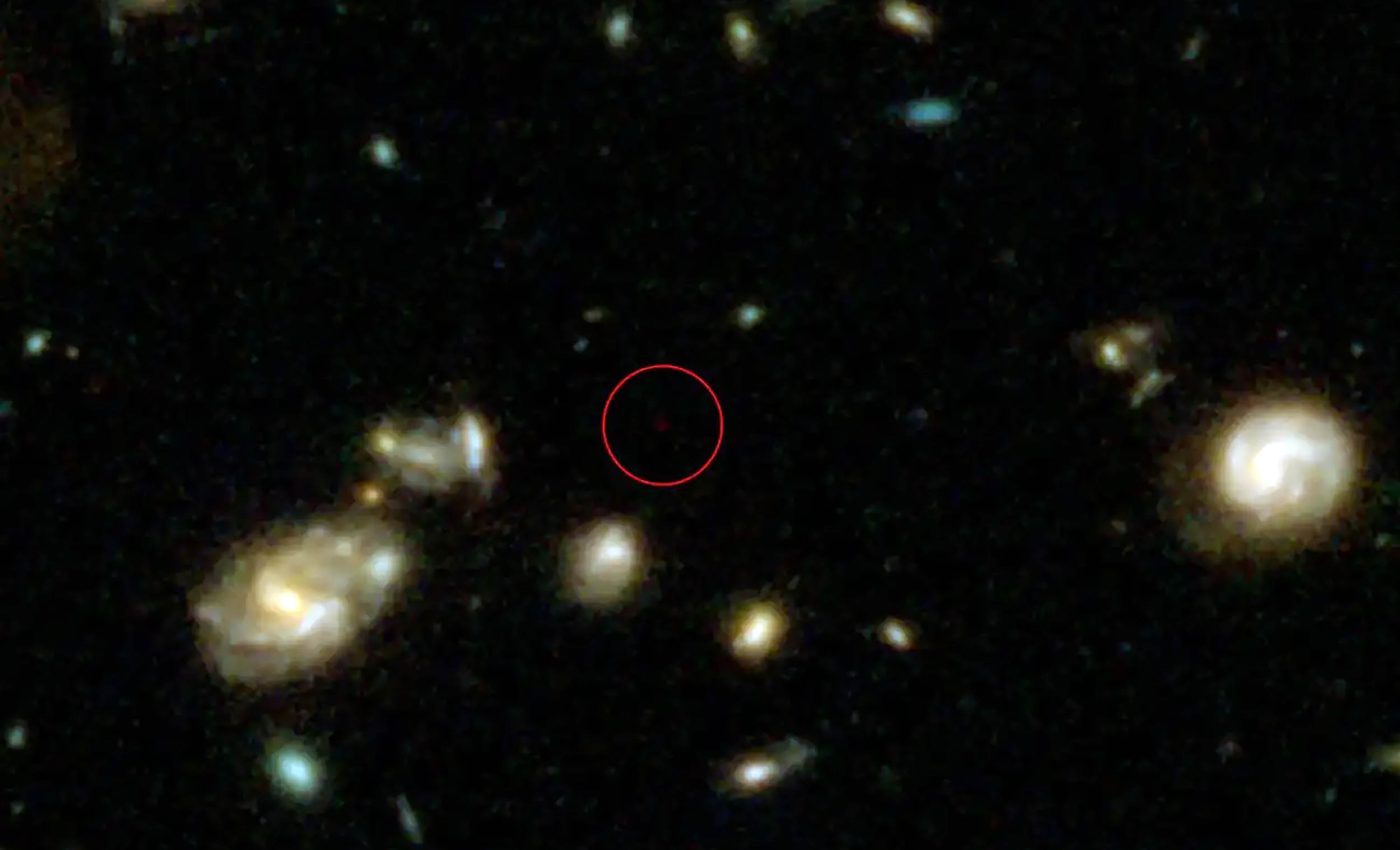

The galaxy looks like nothing more than a tiny smudge. Yet its light appears to have set out when the universe was only about 90 million years old.

The team has nicknamed the object “Capotauro,” but they’re the first to admit it might turn out to be something else entirely.

Capotauro surprises scientists

Distance in cosmology is measured by redshift: as the universe expands, light from faraway objects is stretched to longer, redder wavelengths.

The current record holder, a distant galaxy called MoM-z14, has a redshift of 14.4. That means we see it as it was roughly 280 million years after the Big Bang.

Capotauro, by contrast, shows an eyebrow-raising photometric redshift of 32. That value, if confirmed, would push the first known galaxies back by nearly 200 million years.

“Capotauro could be the farthest galaxy ever seen,” said Giovanni Gandolfi of the University of Padua, adding that it would lie at a timescale that is compatible with the first stars and black holes to form in the universe.

The candidate popped out of a deep JWST survey as a faint blip. It vanishes in filters sensitive to bluer light, which has been absorbed or redshifted away. The object appears only in the reddest infrared bands, the classic signature of an extremely distant source.

By comparing how bright it looks through different JWST filters, the team estimated its redshift without a spectrum – a common first step for spotting early universe targets.

Too bright for its own good

Capotauro looks very bright for something that young. Its apparent luminosity would imply a mass on the order of a billion suns – comparable to galaxies seen hundreds of millions of years later. That scale is hard to square with theory.

Building a system that big, that fast, would require turning almost all available gas into stars with dazzling efficiency.

“To achieve such a mass, the efficiency at which the galaxy turned gas into stars would have to be close to 100 percent,” said Nicha Leethochawalit of the National Astronomical Research Institute of Thailand. “It means no stars can explode.”

In modern models, feedback from stellar winds and supernovae quickly slows star formation, keeping the efficiency closer to 10–20 percent. “I think there’s something wrong,” she said.

There are, however, other possibilities. If the source is truly at z~32, it might be an ultra-young galaxy caught in the act of assembling.

Alternatively, it could be a more unusual object such as a “black hole star” – a hypothesized behemoth in which a nascent black hole grows inside a massive, puffy envelope of gas. Either way, it would force a rethink of how fast structure took shape in the infant universe.

A cosmic impostor?

The simplest explanation may be much closer to home. Without a definitive spectrum, some foreground impostors can masquerade as extreme redshift galaxies in imaging alone.

Gandolfi and colleagues note Capotauro could instead be a very cold brown dwarf – a failed star – or even a rogue planet within our own galaxy drifting through JWST’s field of view. Its colors, at low temperatures, can mimic the dropout pattern expected for a distant galaxy.

That wouldn’t make the discovery dull. By their estimates, such an object would be unusually remote for a substellar wanderer – perhaps up to 6,000 light-years away – and so cool it would sit near room temperature. “It could be one of the first substellar objects ever formed in our galaxy,” Gandolfi said.

Spectrum will reveal the truth

Sorting these scenarios demands follow-up. The next step is spectroscopy with JWST: splitting Capotauro’s light into its component wavelengths to look for telltale features.

If the source is a genuine high-redshift galaxy, astronomers would expect a sharp cutoff. That cutoff comes from intergalactic hydrogen absorbing light bluer than the Lyman-alpha line.

If it’s instead a nearby brown dwarf, molecular absorption bands from water, methane, or ammonia should reveal its identity.

Leethochawalit favors caution – “If it’s a galaxy with a redshift of 32, many things that we have thought so far would be wrong,” she said – but agrees the object is worth precious telescope time. Even a null result would tighten our understanding of the kinds of contaminants that sneak into early-universe surveys.

Galaxy or impostor, it matters

If astronomers confirm Capotauro at z~32, it will vault ahead of MoM-z14 and the current crop of JWST-era candidates, recasting the timeline for how quickly distant galaxies assembled.

Models would need to explain billions of solar-mass systems emerging within the universe’s first 100 million years. Otherwise, they must invoke different physics – from unusually calm star formation to rapid black hole growth shaping a galaxy’s light.

If it’s a nearby interloper, that outcome still matters. It would expand the census of cold, free-floating objects in the Milky Way and help astronomers refine their methods for separating true cosmic-dawn targets from stellar look-alikes.

This step is critical as JWST and future observatories push deeper into the universe’s earliest chapters.

A preprint of the article can be found on arXiv.

Image Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, CEERS, G. Gandolfi

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–