Ancient forest discovered hidden on a treeless island in the South Atlantic

The Falkland Islands greet visitors with low grasses, rocky ridges, and relentless sea spray. Yet beneath that stern exterior, researchers have just uncovered a buried forest that flourished long before humans or sheep ever set foot on the archipelago.

Six yards down in a construction trench near Stanley, workers hit a mat of dark peat studded with whole trunks.

The surprise was not the wood itself, but the fact that nothing taller than a shoulder‑high shrub grows there today. Dr. Zoë Thomas of the University of Southampton hurried to the site with colleagues, ready to salvage the pieces before they dried and cracked.

Wood that outlived the wind

“The tree remains were so pristinely preserved they looked like driftwood,” recalled Dr. Thomas. Thomas lifted a limb the size of a fence post and found its bark still rough to the touch.

No one knew how long they had rested in the bog, but living trees have been missing from the islands for at least 40,000 years.

The team could not turn to radiocarbon dating, which maxes out at roughly 50,000 years. Instead, they trimmed thin slices and shipped them to Sydney for high‑resolution electron imaging.

Pollen locked in the surrounding peat dated the forest to between 15 and 30 million years ago, a span that straddles the late Oligocene and early Miocene.

The mix included beech relatives in the genus Nothofagus and several podocarps, matching patterns reported in the full research paper.

Two stout logs showed growth rings close together, hinting at cool summers even during this warmer epoch.

Their cell walls bore the hallmarks of podocarp wood, a group that still dominates cool temperate rainforest in modern Patagonia, underscoring the ecological link between the distant cousins.

Reading pollen like a calendar

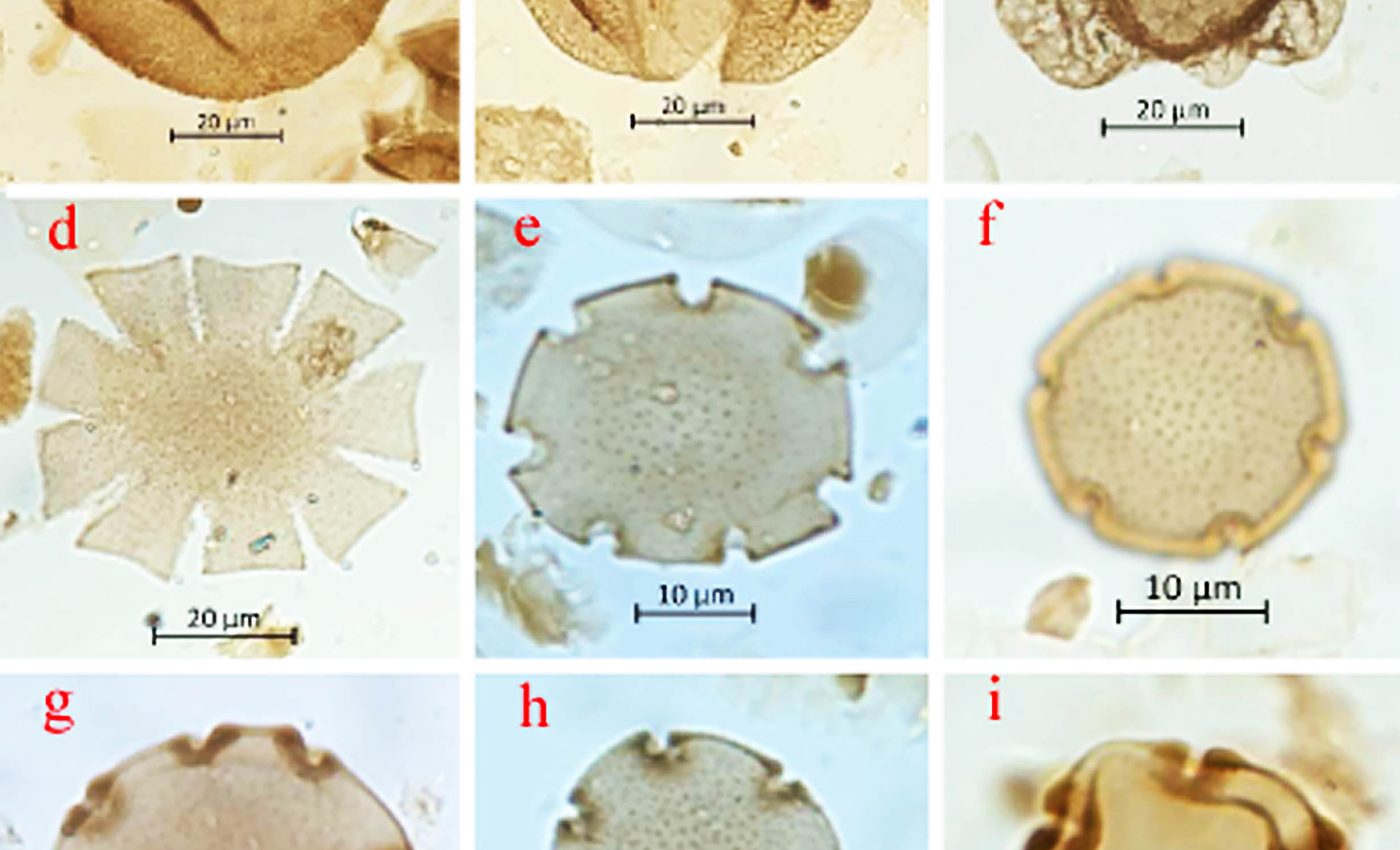

The job of decoding those grains falls to palynology, the study of microscopic spores and pollen. Under a microscope, each grain’s surface pattern acts like a bar code that links it to a species and, by extension, to a geologic era.

“The fossil pollen, spores, and wood paint a much different picture of the ancient environment, providing direct evidence of cool, wet forests,” noted Michael Donovan, collections manager at Chicago’s Field Museum.

More than 60 percent of the sample came from podocarp conifers, while about 25 percent carried the three‑lobed signature of Nothofagus pollen.

Rare grains from warmth‑loving families such as Sapindaceae hinted that South American seeds were wafting eastward across hundreds of miles of open ocean during warm intervals of the Cenozoic.

Microscopic charcoal was scarce, an encouraging sign that wildfires rarely disturbed the ancient canopy. That quiet fire record aligns with a wetter climate than the modern islands enjoy.

Researchers also sifted for marine algae spores, a trick that reveals whether sea water ever lapped over the deposit. Their absence shows the forest stood on dry ground, likely a low valley later blanketed by peat as the climate cooled.

How the islands lost their trees

Today the Falklands sit at 52° S and average just 42 °F year‑round with gusts that routinely top 40 mph. Those bitter maritime conditions, together with nutrient‑poor peat, keep seedlings from pushing above the grass.

Strengthening westerly winds, documented across the Southern Hemisphere over the past century, intensify the stress by blasting salt spray far inland.

The peat itself may work against new growth by locking up nutrients in acidic water. Ecologists who have tried experimental plantings report that saplings break at the first major gale unless sheltered by artificial windbreaks. Taken together, climate and soil form a near‑perfect barrier against a second natural forest.

Geologists think the islands have hovered near their present latitude since Gondwana fractured, so tectonic escape cannot explain the deforestation.

Instead, cooling after the Miocene Climate Optimum and a regional drop in rainfall likely squeezed the forest until only shrubs remained.

Window into South Atlantic climate

Finding a temperate rainforest at this latitude underscores how warm the mid‑Cenozoic could become when atmospheric carbon dioxide climbed above modern levels.

Climate simulations for the Miocene put average Falklands temperatures around 55 °F and annual rainfall nearly double today’s totals, conditions that match the biological evidence in the peat.

Those same models show that stronger westerlies funnel moisture toward Patagonia while drying the islands, hinting that the buried forest may hold a high‑resolution record of wind shifts.

In turn, such shifts modulate Antarctic sea‑ice and global carbon uptake, making the peat bed a valuable target for future isotope work.

By analyzing stable isotopes in the wood cellulose, researchers hope to reconstruct year‑to‑year rainfall and test the model predictions.

The approach could reveal whether abrupt wind changes lined up with global tipping points such as Antarctic glaciation.

Peat, preservation, and future risks

“Current projections suggest the region will get warmer but also drier, leading to concerns about the risk of erosion to the peatlands,” she cautioned.

The peat that embalmed the trunks also locks away tons of carbon. As the South Atlantic warms, Thomas worries that drier summers could crack the surface and let oxygen race in, turning the bog from a sponge into a source of greenhouse gases.

Local conservationists already fight soil loss where tussac grass has been overgrazed by livestock. The newly reported site lies only a few feet above high tide, so any rise in sea level or storm surge could scour out the deposit and erase a chapter of Southern Hemisphere history.

Preserving the trench and the samples it yielded will allow future scientists to mine the pollen layers for fresh clues about ocean currents and storm tracks.

Uncovering a forest where none should exist reminds researchers that landscapes can flip between extreme states when climate crosses hidden thresholds.

Studying those thresholds, tree by fossilized tree, may refine predictions for the winds, rains, and ecosystems of the next century.

The study is published in Antarctic Science.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–