Barbie crabs, sea pigs, and 40 new species discovered in a giant underwater canyon

An Argentine research team just finished a first-of-its-kind look into the Mar del Plata Canyon, a deep South Atlantic gorge that drops to about 11,500 feet. They used a robot to see habitats that nets could only hint at, and the footage held a nation’s attention.

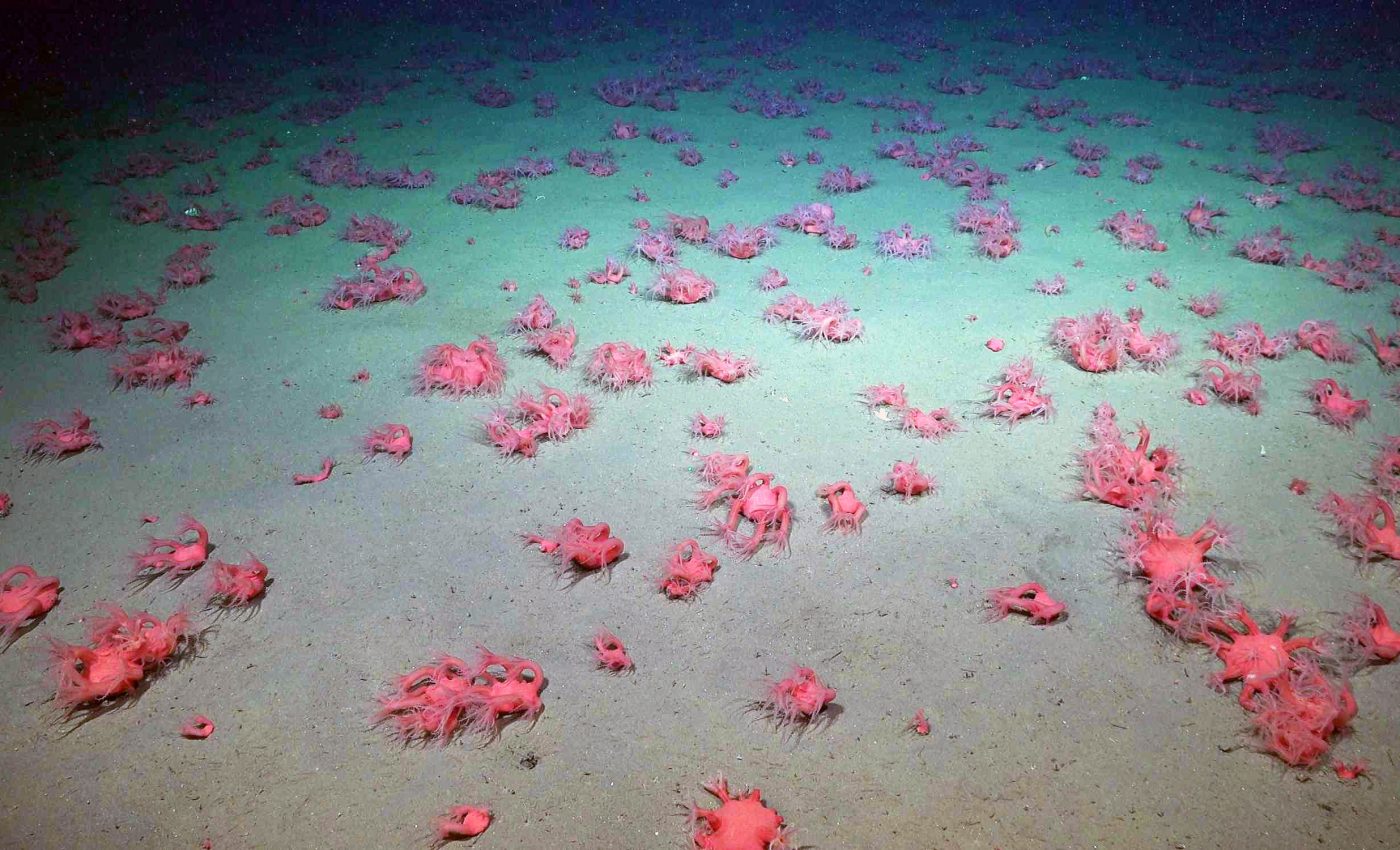

Viewers watched coral fields, rare invertebrates, and odd creatures glide through the dark. Early counts suggest around 40 organisms may be new to science, a list that spans anemones, sea cucumbers, sea urchins, snails, and crinoids.

Meet the team and their tools

The expedition was led by Dr. Daniel Lauretta of CONICET and the Bernardino Rivadavia Natural Sciences Argentine Museum.

It explored a canyon about 186 miles off the coastal city of Mar del Plata, with the deepest points beyond 3,500 meters, which is more than 2 miles.

The team used a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) that pilots control from the ship through a tether. It carries high definition cameras, lights, manipulator arms, samplers, and sensors that work in cold, high pressure water.

“It was a huge surprise for us. It’s something that fills our hearts because we want to spread the word,” said Lauretta.

Across Argentina, the livestream drew more than 1.6 million daily views and often 50,000 simultaneous watchers.

Mar del Plata Canyon

A submarine canyon is a steep, riverlike cut in the seafloor that channels sediments and organic matter from the shelf into the deep.

These corridors can create sharp changes in terrain and currents that concentrate food and shelter.

Mar del Plata Canyon lies where two major currents meet in the Brazil-Malvinas Confluence. One current brings warm, salty water from the north, while the other carries cold, nutrient rich water from the south.

That meeting zone is one of the most energetic places in the South Atlantic. Eddies spin, temperatures shift quickly, and boundaries form that help structure which species can live where.

What the cameras found

A BBC Wildlife report describes a stony coral reef of Bathelia candida around 3,330 feet down, and a broad field of red Anthomastus soft corals near 4,920 feet. Those coral structures create habitat that other animals use for shelter and feeding.

The stony coral Bathelia candida is an accepted species in the family Oculinidae. Its skeleton adds three dimensional structure to the seafloor and can support dense communities.

Animals recorded included shimmering squids, deep sea lobsters, and sea pigs, a type of sea cucumber that trundles over the mud.

A bright orange seastar drew public comparisons to a cartoon character because of its shape and color.

New species in Mar del Plata Canyon

Finding an organism that looks new is only the start. Taxonomic work compares body parts, spines, plates, and other features with museum specimens and published descriptions to ensure a species is not already known.

Teams also use environmental DNA to help detect presence.

That is genetic material shed by organisms into water that can be filtered and sequenced to cross check which groups live in a place, even if the camera missed them.

The formal path includes writing a description, selecting a type specimen, and submitting a paper for peer review. That process can take months or years, especially when families include many similar looking species.

Real time video let classrooms, families, and workers watch the same scenes as the science team. That shared experience can turn curiosity into study paths, careers, and community support for research.

The team also saw shoes, plastic bags, and lost fishing gear on the canyon floor.

Those finds show how human activity reaches remote places, and they give managers evidence to consider when planning protection or cleanup.

Mar del Plata Canyon’s importance

The canyon cuts into the wide Patagonia shelf, which spreads shallow water far from shore. That placement funnels sediments and nutrients downslope, which can feed filter feeders like corals and sponges.

It also overlaps with the confluence where water masses meet and mix.

Those conditions promote sharp ecological boundaries along the canyon walls and floor, offering natural laboratories for studying how communities change with temperature and chemistry.

Long records from this area can track how species respond to shifting currents and heat content. That is valuable for fisheries and conservation because signals here can project changes along the shelf.

How the tools changed the game

Earlier work in this region relied on trawls and nets that pull up animals but do not show where they lived. ROVs preserve context by filming animals in place, recording behavior, and sampling only when needed.

The robot’s arms collected small pieces of coral for identification and growth analysis. Cameras documented whole communities, from anemone meadows to solitary fishes hovering over burrows.

Sampling also included cores that capture sediments and any microplastics trapped inside. Together, these methods create a baseline for future checks, which helps track whether habitats improve or decline.

Next up for Mar del Plata Canyon

Scientists will identify the most likely new species first and prioritize specimens most at risk of damage if left unpreserved. Teams will share data with colleagues who work on DNA barcoding, imaging, and taxonomy.

The group plans to compare patterns in this canyon with similar depths elsewhere in the South Atlantic. That helps separate local quirks from broader trends driven by currents and water mass changes.

The expedition also set a new bar for public engagement. Live access to discovery, clear commentary, and simple explanations brought people together around science in an ordinary week.

Click here to view photos and videos from this expedition…

Image credits: ROV SuBastian / Schmidt Ocean Institute.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–