Invasive parasitic wasps quietly crossed oceans, now thriving in U.S. oak trees

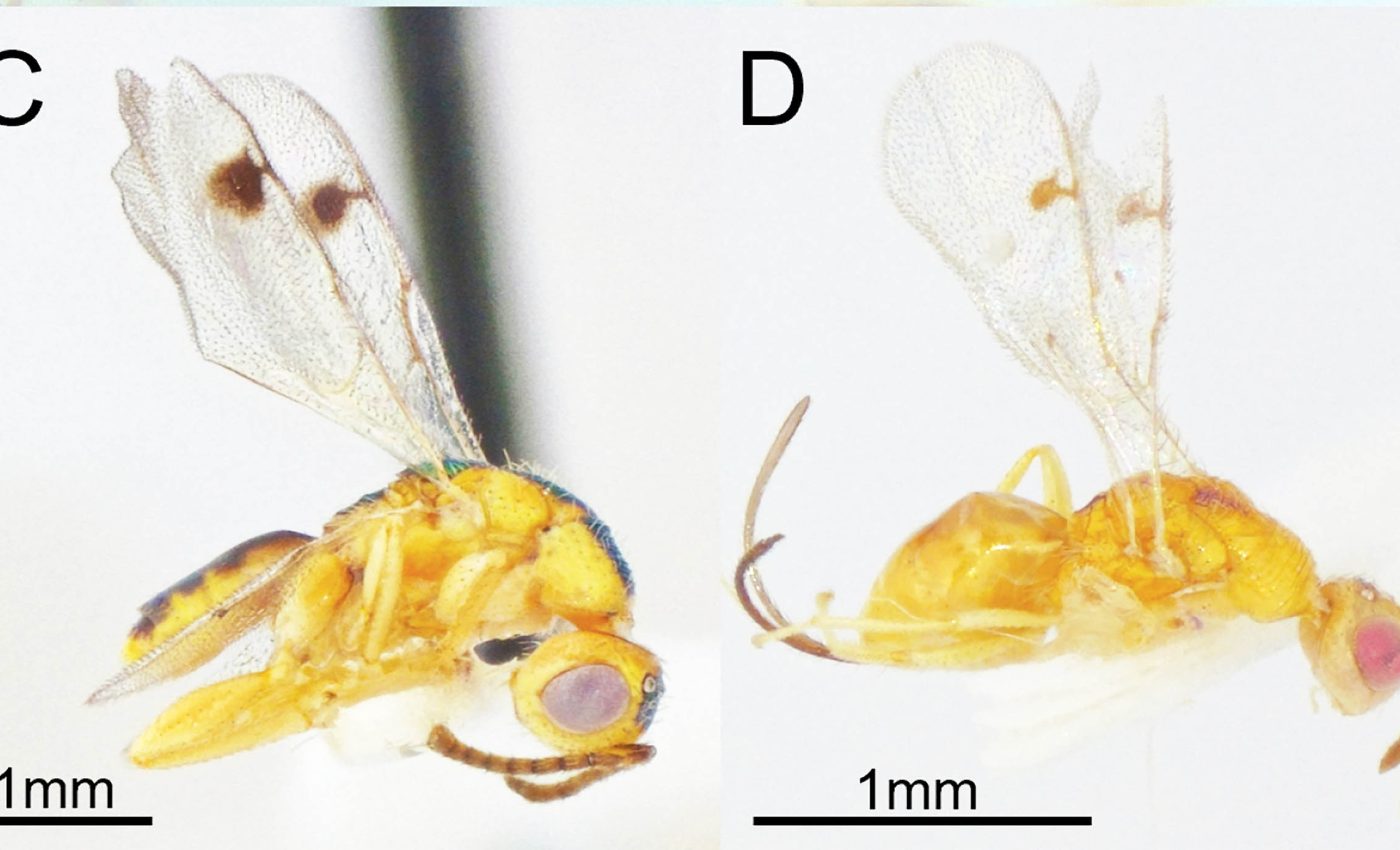

Parasitic wasps aren’t winning beauty contests anytime soon. They’re not colorful like butterflies or flashy like fireflies. They’re about the size of a grain of rice – or smaller – and they spend much of their lives inside plant lumps called galls. But these tiny insects just gave scientists a big surprise.

Two previously unknown species of parasitic wasps were discovered living in North America. They didn’t evolve here. They hitched a ride – and no one really noticed until now.

The secret lives of gall wasps

Across North America, oak trees host a strange cast of insect tenants. One of the oddest is the oak gall wasp. These wasps lay their eggs in oak trees, which causes the trees to form protective structures called galls.

These galls come in wild shapes and sizes – some look like fuzzy balls, others like spiky marbles or tiny apples. Inside the galls, young oak gall wasps grow. But they’re not alone.

Parasitic wasps come along and lay their own eggs inside the galls. Their larvae then feed on the oak gall wasp larvae, killing them in the process. It’s not pretty, but it’s part of how nature works. And it turns out, this hidden world is far more complicated than anyone thought.

Genetics uncover hidden invaders

Recently, scientists found something strange. On both the East and West Coasts of North America, they were collecting parasitic wasps from oak galls.

But some of the wasps didn’t look quite right. To get answers, researchers turned to genetics. They looked at a gene often used to identify insect species – kind of like scanning a barcode at the grocery store.

The results were unexpected. The wasps matched a European species called Bootanomyia dorsalis. But not just one version. The West Coast wasps were genetically similar to those from Spain, Hungary, and Iran. The East Coast wasps were closer to those from Portugal, Italy, and Iran.

The two groups were different enough that scientists now believe they’re actually two separate species. And both of them somehow made it to North America.

Wasps hitch rides across seas

On the West Coast, these wasps were found from Oregon to British Columbia. All the samples were genetically identical, which means the introduction was small – probably just a few insects. But they managed to spread.

On the East Coast, the wasps had a little more genetic variety. That could mean they arrived more than once or came from a larger group.

How did they get here in the first place? One theory is that they came along with oak trees brought over from Europe.

English oak has been planted in North America since the 1600s, and Turkey oak is a popular ornamental tree. Both are found in areas where the wasps were discovered. Or maybe they simply flew in.

“Adult parasitic wasps can live for 27 days, so they could have hitchhiked on a plane,” said Kirsten Prior, an associate professor of biological sciences at Binghamton University.

Tiny wasps, big ecological risks

These tiny newcomers might not seem like a big deal, but they could have real effects on native insects.

“We did find that they can parasitize multiple oak gall wasp species and that they can spread,” Prior said. “They could be affecting populations of native oak gall wasp species or other native parasites of oak gall wasps.”

Parasitic wasps are important for ecosystems. They help control insect populations – including pests that damage crops and forests.

But when new species show up, they can disrupt delicate ecological balances. The discovery of these two wasps shows just how much there is still to learn.

“Parasitic wasps are likely the most diverse group of animals on the planet and are extremely important in ecological systems, acting as biological control agents to keep insects in check,” Prior said.

Ambitious project uncovers invaders

Graduate students have been traveling across North America, collecting oak galls and sequencing the DNA of the insects inside. It’s the most ambitious study of its kind.

“We are interested in how oak gall characteristics act as defenses against parasites and affect the evolutionary trajectories of both oak gall wasps and the parasites they host,” said Prior. “The scale of this study will make it the most extensive cophylogenetic study of its kind.”

And the discoveries keep coming. Over the past few years, her lab has collected about 25 oak gall wasp species and reared tens of thousands of parasitic wasps. That work uncovered over 100 species – and two of them had never been recorded in North America before.

Backyard science fuels discovery

You don’t need a PhD to help. Many discoveries come from everyday people exploring their own backyards.

Projects like Gall Week on iNaturalist encourage people to collect galls and share their findings. Even students at Binghamton University have gotten involved through events like Ecoblitz.

“Only when we have a large, concerted effort to search for biodiversity can we uncover surprises – like new or introduced species,” Prior said.

In a time when biodiversity is under pressure from global change, every small discovery helps paint a bigger picture. And sometimes the most important stories come from the smallest creatures.

This finding came out of a larger project funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation. Researchers from Binghamton University, the University of Iowa, Wayne State University, and Gallformers.org are working together to better understand oak gall wasps and the parasites that live with them.

The full study was published in the journal Journal of Hymenoptera Research.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–