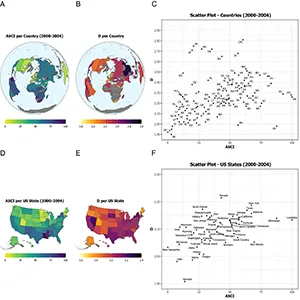

State and national maps created that label regions with the most psychopathic people

A major global study links higher levels of Dark Factor of Personality and psychopathy-related traits to places with more poverty, inequality, violence, and corruption. It pulls data from 1.79 million people in 183 countries, plus 144,576 Americans across all 50 states.

The headline result is simple. Where harsh conditions persist, more people score high on traits tied to exploitation and callousness.

Dark Factor of Personality

The project centered on the Dark Factor of Personality (D) a common core of harmful traits that favor self interest over others. It is often shortened to D in research.

The authors explained that D represents a general tendency to maximize one’s own benefit while disregarding or even causing harm to others. They noted that this definition distinguishes D from any single dark personality label.

Researchers from the University of Copenhagen analyzed the Dark Factor of Personality across 183 countries and all 50 U.S. states, comparing how social conditions shape levels of self-serving traits worldwide.

They also tested timing. The main analyses compared today’s Dark Factor scores to societal conditions measured roughly 20 years earlier.

Societal conditions and Dark Factor

The study examined aversive societal conditions, corruption, inequality, poverty, and violence grouped into one index. That cluster captures environments where rule breaking often goes unpunished.

Two pathways help explain the link. First, when exploitation is common, defensive selfishness can seem safer than trust.

Second, people learn from their surroundings. If rule bending appears normal, beliefs can shift toward cynicism and self gain.

Effects were small for any one person but consistent at scale. Small averages can add up when applied to millions of lives.

Dark Factor personas in the U.S.

Within the United States, Nevada had the highest average Dark Factor of Personality score, followed by New York, with Texas and South Dakota close behind. Vermont ranked lowest, with Utah and Maine next.

These results point to patterns, not diagnoses. High D suggests more willingness to harm or exploit others for personal gain.

The team did not label anyone a psychopath. D captures a general tendency that can appear as psychopathy, narcissism, Machiavellianism, or related traits.

State differences were modest but clear. The pattern aligns with the broader link between tough conditions and self serving behavior.

How the data were built

For corruption, the global inputs included World Bank governance indicators summarizing how much public power is used for private gain.

To measure violence in the U.S., the researchers used FBI homicide data, which provides one of the most reliable indicators of how often lethal crimes occur. These rates offer a clear snapshot of how dangerous a community’s conditions may be.

Inequality was captured using the Gini, a single number that summarizes how uneven incomes are. Higher values mean wider gaps between top and bottom.

Data on corruption came from U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) reports that document convictions of public officials. These records trace how often and where government corruption has been prosecuted over the years.

Study limitations

Online samples can skew toward people who opt in. The authors flagged self-selection as a limitation when interpreting the averages.

Residence length was unknown for many participants. Without that detail, it is hard to say how long local conditions had to shape their personalities.

Corruption and violence are hard to measure cleanly. Even well constructed indices can miss local nuances.

Even with those limitations, the overall pattern stayed consistent when the team tested alternate measures and time periods.

The connection between social conditions and dark personality traits remained strong after adjusting for age and gender.

Why these patterns matter

Understanding why Dark Factor of Personality traits cluster in certain regions helps explain how environments shape behavior over time.

When people grow up in places where inequality and corruption feel normal, they may learn that self-preservation and manipulation are effective strategies.

Over generations, those attitudes can become embedded in a region’s culture.

The researchers emphasized that these findings do not label individuals as bad or immoral. Instead, they reveal how persistent hardship and weak social trust can tilt populations toward competitive and distrustful mindsets and personalities.

Recognizing these influences offers a clearer path to designing fairer and more cooperative societies.

Dealing with Dark Factor of Personality

The finding suggests a policy lever. If corruption falls and basic security improves, average D may drop over time.

That will not happen overnight. Personality shifts gradually, and social norms change step by step.

Still, small changes can matter once multiplied across large populations. Less exploitation means fewer daily harms to neighbors, coworkers, and strangers.

Understanding Dark Factor of Personality also changes the conversation. It shifts the focus from labeling individuals to improving the conditions that nudge many of us toward better behavior.

The study is published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–