Webb finds a possible direct-collapse black hole between two galactic nuclei

Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope have spotted an object, named the Infinity Galaxy, that turns a basic rule of galaxy evolution on its head – a likely direct collapse black hole.

These objects form directly from the collapse of a massive gas cloud instead of from a dying star, sits not inside a galaxy’s core but between two colliding galactic centers, embedded in a cloud of gas.

The system, nicknamed the Infinity Galaxy for its figure eight shape, appears to host three active black holes at once.

One sits in each compact nucleus, and a third, about a million times the Sun’s mass, glows between them as gas falls in.

Studying the Infinity Galaxy

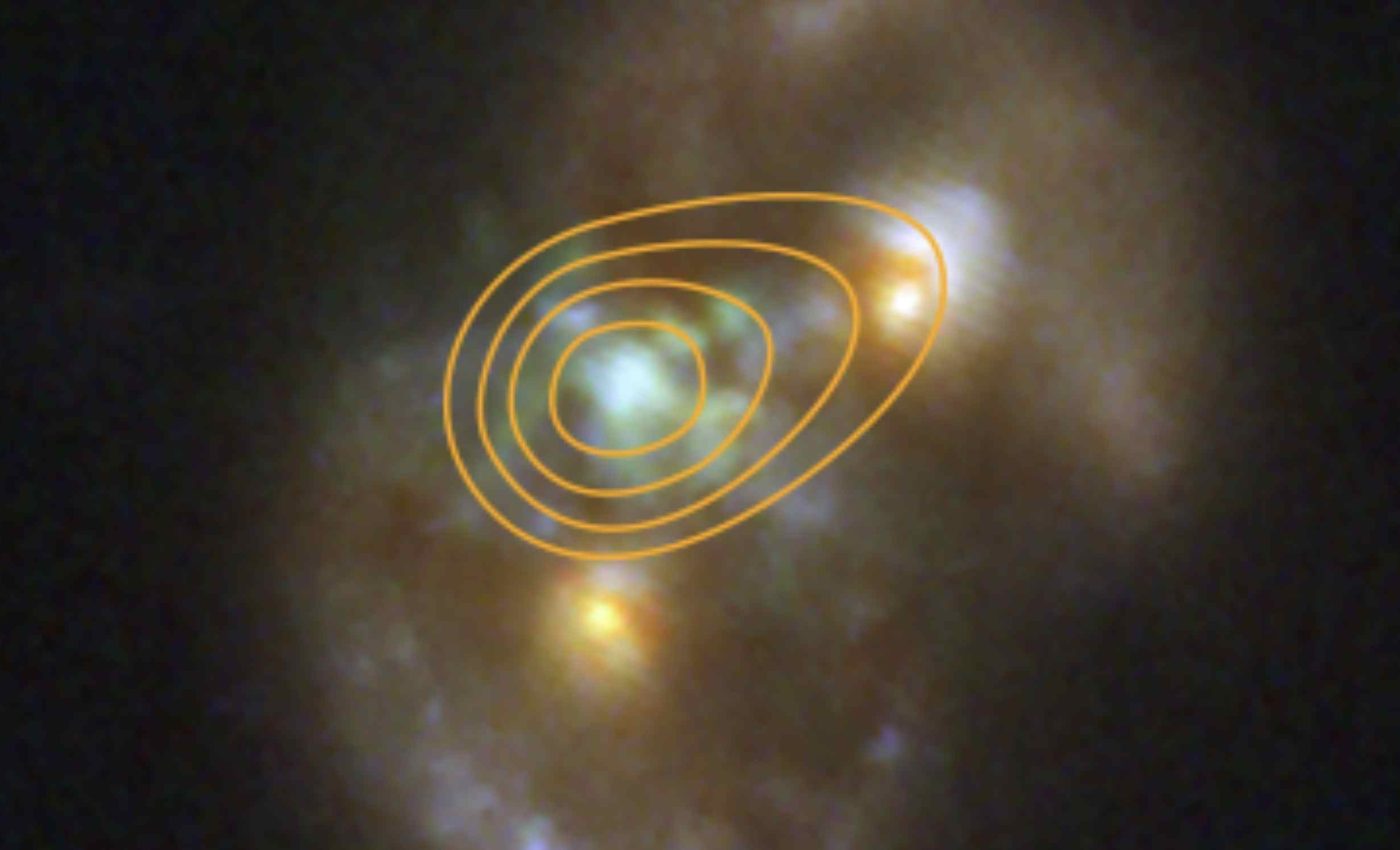

NASA described the discovery on July 15, 2025. The Webb image shows two tight, red cores wrapped by starry rings and a bright knot of activity in the middle.

Pieter van Dokkum of Yale University led the analysis and coordinated the follow up program.

His team combined data from the Webb Telescope, the Chandra X-ray Observatory, and the Very Large Array to confirm that the middle source is active and rapidly feeding, building a strong case that it was born from the same gas cloud between the two galaxies.

The data suggest that two disk-shaped galaxies crashed into each other head on, creating twin rings of stars and the figure eight shape.

The team’s first analysis, estimates that the system lies billions of light years away and shows two dense centers formed by the collision.

Gas at the collision site is lit up as ionized gas, meaning atoms with electrons stripped away, and that glow marks where the interloper black hole sits. The bright middle source draws in material and lights nearby hydrogen.

Why the location matters

A supermassive black hole usually anchors a galaxy’s center where stars and gas orbit in a deep gravitational well. Here, the middle engine is off center, and both nuclei also show signs of active feeding.

The accretion signal includes X rays and radio light. The feeding signature shows in X rays from Chandra and in radio data from the Very Large Array, a network of radio dishes that tracks how matter falls toward a black hole.

How to make an Infinity Galaxy

Astronomers frame the growth of the earliest monsters with two ideas, light seeds and heavy seeds. Light seeds start as small black holes from stellar deaths, then merge and feed over long times to become giants.

“Finding a black hole that’s not in the nucleus of a massive galaxy is in itself unusual, but what’s even more unusual is the story of how it may have gotten there,” said Pieter van Dokkum.

Heavy seeds start big, forming when a huge cloud of gas collapses directly under its own gravity instead of going through the usual star stage.

This shortcut allows a black hole to grow much faster, which could explain why some of the earliest galaxies already held giants at their centers.

Unexpected positioning

The team’s greatest surprise was that the black hole wasn’t sitting inside either galaxy’s core but directly between them.

That unexpected position raised new questions about how such an object could have formed in open space rather than within a galactic nucleus.

“We observe a large swath of ionized gas, specifically hydrogen that has been stripped of its electrons, that’s right in the middle between the two nuclei, surrounding the supermassive black hole,” said van Dokkum.

Putting the idea to the test

A sharp test compares motions. If the middle engine formed from the gas between the galaxies, its speed should match that gas within about 30 miles per second.

The team reasoned that if the black hole’s motion matched the surrounding gas within about 30 miles per second, it would strongly suggest that it formed from that same material.

Follow up results confirmed that the black hole’s velocity fits neatly within that range, supporting the idea that it was born in place.

The same study also confirms AGN style emission in both galactic cores, meaning there are three active engines in the system. That triplet helps rule out a recoil or ejection as the origin for the central object.

Ruling out look-alikes

One possible explanation is that the object is a runaway black hole, ejected from an earlier galaxy merger and now drifting through the gas between the two galaxies.

Another idea is that a small, faint third galaxy lies directly along our line of sight, hiding its own central black hole within the overlapping view.

Spectroscopic observations helped measure the motion of the gas and the width of emission lines around each nucleus.

The very broad hydrogen lines in both cores indicate the presence of active black holes, making it unlikely that the central source was ejected from either one..

What JWST adds

Webb’s infrared images reveal the twin rings and bright spots with remarkable detail, clearly separating dust and older stars.

This sharp view allowed the team to track how fast the black hole and nearby gas are moving and see that their motions align.

The research team analyzed data from the COSMOS-Web survey to search for unusual patterns, then combined those findings with radio and X-ray observations to strengthen the case for a newly formed black hole.

Why the Infinity Galaxy matters

JWST has revealed supermassive black holes in very young galaxies only a few hundred million years after the Big Bang.

Light seeds struggle with that timeline because small black holes need many steps of merging and feeding to bulk up.

The Infinity Galaxy offers a nearby test of heavy seed physics in a place where conditions look right for a direct collapse.

A violent collision compresses gas, slows star formation in the crash zone, and leaves enough material in one spot to fall inward fast.

The heavy seed case rests on a velocity match, the extended gas glow, and the lack of a strong host around the middle engine.

Those align with formation in place, but models must still show that the gas can collapse without breaking into many stars.

The team is analyzing deeper spectra to track metal content, turbulence, and gas density across the bridge.

More data will show how quickly the black hole is growing and whether it can explain the huge engines that Webb sees in very early galaxies.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–