The Y chromosome is disappearing, a fact that is already causing problems for men

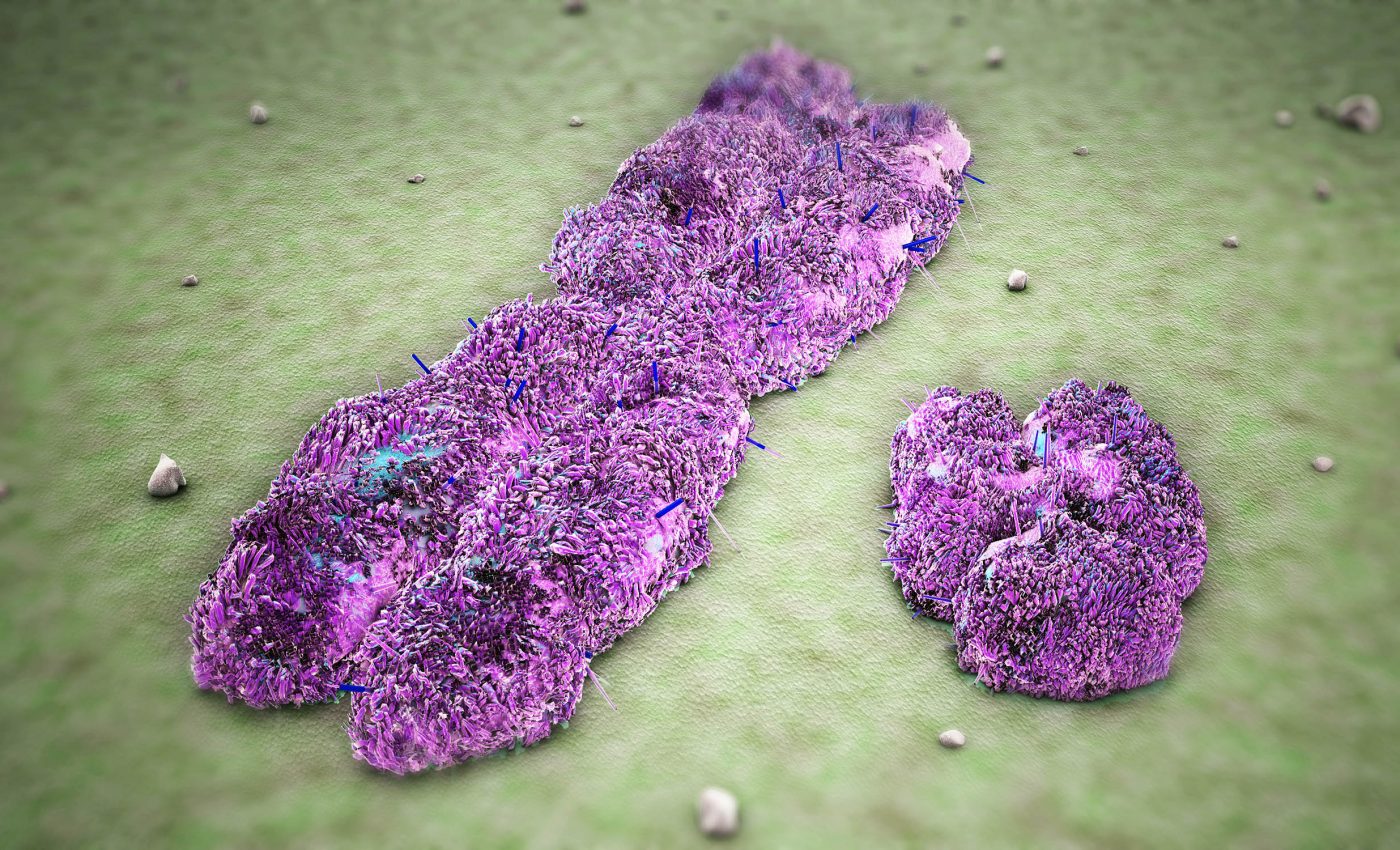

Flip open a high-school biology textbook, and the rule seems tidy: two X chromosomes mean girl, and an X paired with a Y means boy. That much smaller Y chromosome carries the SRY gene, which is the switch for testis development.

For the last 300 million years or so, this system has been working very well. Now, however, chatter in genetics circles hints that something is amiss.

Over time, the Y chromosome has been losing pieces of itself, and computer models suggest the last scraps could vanish in roughly 11 million years.

Y chromosome loss (LOY) no trivial matter, because what it holds – or drops – can sway everything from cancer risk to how future humans reproduce.

Would that erase men from the planet, or would life simply shrug and invent a new plan? Rodents on remote islands and subtle changes inside aging human bone marrow are now providing clues.

One story shows how a mammal kept producing males after its LOY disappeared entirely. The other warns how men already pay a price when some of their cells drift away from the chromosome during middle age.

Y chromosome fade away

The X chromosome carries about 900 genes that do everything from wiring nerves to repairing DNA. Its partner, the Y, keeps only about 55.

Comparative work across mammals shows that, once our lineage split from the platypus some 166 million years ago, the Y began dropping about five genes every million years. Run that line forward, and the ledger hits zero in 11 million years – a geological heartbeat.

Most biologists once chalked that outcome up to hype. After all, many species never shed their sex chromosomes.

But the idea gained traction when researchers found the Japanese spiny rat and a few mole vole species thriving today without any Y chromosome at all. Somehow, they had rewired the traditional circuit for making testes.

Rodents changed the rules

In 2022, scientists found a duplicated piece of DNA near a gene called SOX9 in the spiny rat. Usually, another gene (SRY) turns SOX9 on to make male traits develop.

But in this rat, the new DNA copy does that job on its own – even without a Y chromosome – so a genetically female animal (XX) can still develop as male.

Drop the fragment into lab mice and testes still form. Evolution, it seems, can lay a new cable when the old one burns out.

That discovery hints that, should the human Y fizzle out one distant day, natural selection could promote an alternative trigger.

Different populations might even settle on different triggers, eventually splitting into separate species that cannot interbreed. The idea sounds like science fiction, but the rodent reality shows it is genetically feasible.

Y chromosomes and men’s health

Long before any species-wide overhaul, countless men are already losing the Y chromosome cell by cell. Starting in their fifties, bone-marrow stem cells sometimes mis-segregate it during division.

The resulting white-blood-cell lineages, missing their Y, multiply quietly. By 80 years old, more than 40 percent of men carry sizable pockets of this “mosaic loss of Y” in their blood.

Tracking 1,153 Swedish men in their seventies and eighties, researchers found that those with the loss died 5.5 years earlier, suffered more solid tumors and heart disease, and faced a seven-fold rise in Alzheimer’s.

Kenneth Walsh of the University of Virginia then bred mouse blood stem cells without the Y chromosome and transplanted them. The recipients developed fibrosis, failing hearts, and early death, showing the loss is the culprit, not a bystander.

Enhanced cancer risk

In another study released in June 2025, researchers mapped LOY across thousands of individual cells from human cancers and matched mouse models.

They found that Y-negative cells were not limited to the tumors themselves; they also dominated the surrounding immune landscape.

CD4⁺ helper T cells shifted toward a regulatory identity that dampens attack signals, while CD8⁺ killer T cells lost much of their punch.

The degree of LOY in the bloodstream mirrored what the team saw inside the tumor. Patients whose blood showed a high percentage of Y-negative white cells tended to harbor tumors rich in LOY and faced poorer outcomes.

Those correlations held across lung, bladder, and head-and-neck cancers, hinting at a common mechanism rather than a disease-specific quirk.

Direct link to the immune system

A gene on the Y chromosome called UTY helps control the immune system. Without it, some immune cells stop working properly – one kind makes more scar tissue, and another becomes weaker, which helps cancer grow and spread.

In mice, tumors grow twice as fast without the Y. In men, bladder cancers missing the Y chromosome are more dangerous – except they respond better to a certain kind of cancer treatment called checkpoint inhibitors.

The picture is complicated: a chromosome that underpins male development also tames inflammation and restrains tumors, yet its selective absence can make some drugs shine.

Medicine and evolution rarely share the same bottom line. Natural selection prizes reproductive success over a lifetime, while clinicians care about the here and now.

Offsetting Y chromosome loss

Cigarette smoke, air pollution, and certain industrial chemicals add extra DNA damage and accelerate the Y chromosome loss. Kicking tobacco, breathing cleaner air, and limiting exposure to mutagens therefore rank as simple defenses – all it takes is willpower.

General habits that slow genomic wear – regular exercise, Mediterranean-style meals, and solid sleep – may also keep the Y chromosome in more cells for longer.

Antifibrotic drugs cleared for lung disease are being tested to blunt heart damage from the loss. Oncologists already use chromosome status in bladder tumors to steer checkpoint therapy.

As single-cell sequencing gets cheaper, your physical exam might soon include a “Y-loss score” beside cholesterol.

Where do we go from here?

The Japanese spiny rat proves that mammals can reinvent the rulebook after the ‘puny little chromosome’ disappears. That prospect keeps evolutionary biologists buzzing.

Yet the rodent’s triumph offers little comfort to a 60-year-old man whose marrow has already shed Y in a third of his white-blood-cell army.

Species-level salvation and individual-level hazard can coexist. That dichotomy – long-term adaptability versus immediate personal cost – will likely guide both medical practice and evolutionary debate in the years ahead.

The Y chromosome is quirky but crucial. It shapes male development, steadies immunity, and may also be plotting its own disappearance.

However, the good news is that the practical advice is simple: dodge mutagens, stub out cigarettes, consider a mid-life test for loss, and keep an eye on new research as this chromosome writes its final chapters.

Let’s go, men, you got this!

The full study was published in the journal Cell.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–