Citizen astronomers captured a possible impact on Saturn for the first time ever

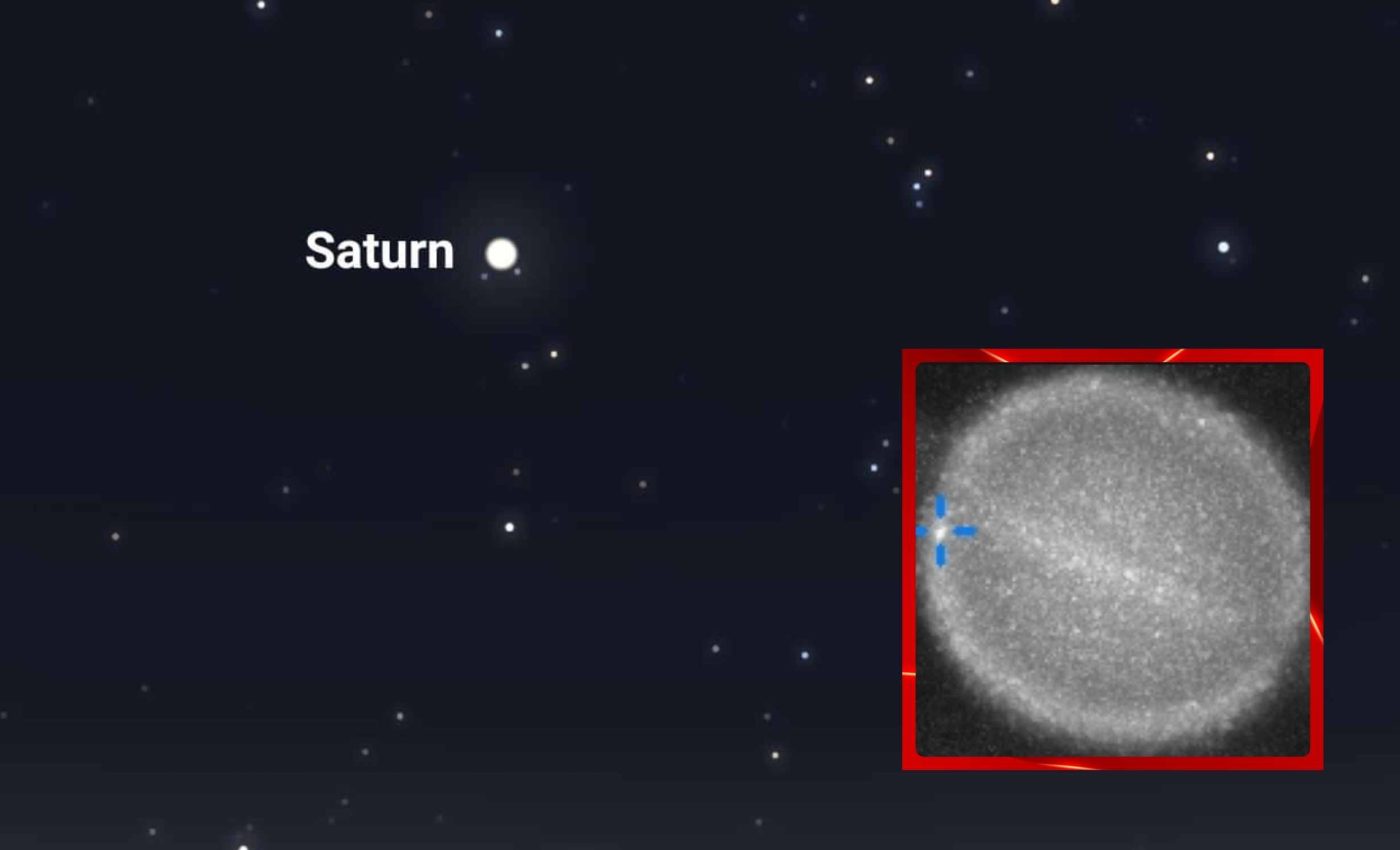

A brief flare lit up Saturn during a home telescope recording session in Hampton, Virginia a few weeks ago. The flash appeared between 9:00 and 9:15 UTC. If it marks a real strike, it would be the first time anyone has captured an impact on Saturn on video.

The moment is unconfirmed, and that uncertainty matters. A single bright frame can come from sensor noise, a satellite crossing the field, or an artifact of processing, so independent recordings are essential.

The Planetary Virtual Observatory and Laboratory (PVOL) team issued a public call for observers who filmed Saturn that morning to share their footage for cross checks.

What the video shows

The recording was made by Mario Rana of NASA Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, who is an experienced astrophotographer and frequently contributes to community imaging projects.

However, one detection does not make a case. Confirming an impact requires the same flash in separate videos, ideally from widely spaced locations, or the presence of a short lived atmospheric mark that rotates with the planet.

Volunteers often use DeTeCt, a free tool developed within the planetary imaging community, to scan video for transient flashes on the giant planets.

This has flagged several Jupiter impacts for follow up since 2010. Cross validation is the guardrail against fooling ourselves with a once-off blip.

Estimating Saturn’s impact size

Large objects are rare visitors. A 2025 analysis that combined outer solar system dynamics with observed small body populations estimated Saturn’s impact rate by objects at least 1 kilometer across at about 3.2 × 10−3 per year. That is roughly one event every 3,125 years.

This number highlights why patient, distributed watching is needed to catch even a single confirmed strike.

“These new results imply the current-day impact rates for small particles at Saturn are about the same as those at Earth,” said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Smaller projectiles are far more common, and Saturn’s rings have acted like an enormous detector for them.

What makes Saturn tricky

Saturn is a gas giant with no solid surface to scar. Its upper layers are mostly hydrogen and helium that can swallow energy without leaving long lasting marks.

That makes a fleeting flash, or subtle changes in cloud texture, the most likely signs of a hit.

A flash near the planetary limb is even harder to confirm because of contrast, limb darkening, and edge processing artifacts.

Without second and third recordings, the community will treat it as an intriguing candidate and nothing more.

Why impacts on Saturn matter

Studying collisions on gas giants helps scientists estimate how often stray objects move through the outer Solar System.

Each confirmed flash provides a real data point to compare against computer models, tightening estimates of how frequently Saturn, Jupiter, and even Earth get struck.

These events also give insight into the composition and behavior of the impactors themselves. By measuring the brightness and duration of a flash, researchers can approximate the size, speed, and structure of the object.

This adds detail to our understanding of the populations of comets and asteroids that share space with the giant planets.

Citizen scientists to the rescue

Amateur observers hold much of the leverage here. Videos recorded that morning using modest telescopes and planetary cameras can carry the precise frames needed to confirm or rule out an impact.

If you captured Saturn that day, keep the original videos and processing logs, and check PVOL’s news feed for submission instructions and contact details for Delcroix, who aggregates potential witnesses for coordinated analysis.

Time stamps in universal time, the exact observing location, and the optical setup are crucial context for any evaluation.

Learning from Jupiter

Jupiter has been the training ground for this kind of citizen science.

In 2010, a small meteoroid, about 8 to 13 meters (26 to 43 feet) in diameter, produced a two second flash that was caught independently by two observers and later analyzed with professional facilities.

Most confirmed Jovian flashes leave no obvious aftermath, a pattern documented in professional and citizen science studies that calibrated light curves to estimate impact energies and sizes.

That record explains why a lack of visible debris on Saturn would not, by itself, disprove a strike.

What comes next

As the videos trickle in, coordinated teams check for the same flash at the same time and location on Saturn’s disk. They also look for telltale processing artifacts that could mimic a pulse of light.

There is already an important update from the DeTeCt project. After scanning additional submissions, the team reported no corroborating detections and concluded there was no impact on Saturn from the July 5th observation.

Even a null result sharpens methods, improves software, and strengthens the network that will catch the next real event.

The study is published in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–