Having an active social life helps the brain make better sense of the world

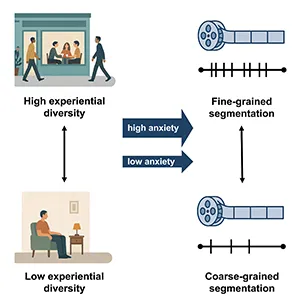

People who lead more varied social lives tend to perceive their days as a sequence of distinct moments, whereas more isolated people experience time as a single, undifferentiated stretch.

The new findings suggest that richer social routines are linked to finer “event segmentation,” a basic process the brain uses to turn the stream of life into manageable chunks.

Researchers at Royal Holloway, University of London, tested this idea with a movie-watching experiment and linked the results to measures of everyday variety.

The study asked 157 young adults to press a button whenever one meaningful moment ended and another began while viewing Alfred Hitchcock’s suspenseful short, Bang! You’re Dead.

Breaking life into moments

Participants who reported greater experiential diversity – especially in their social lives – marked more boundaries, indicating a finer-grained parsing of experience. The association held even after accounting for anxiety, loneliness, and socioeconomic factors.

As our senses take in continuous information, the brain creates “events” so we can remember, plan, and navigate. Event boundaries typically arrive when something important changes: a goal, a place, a character, or an emotion.

People differ in how finely they set those boundaries. The new study shows those differences track with the variety of life outside the lab – and most strongly with social variety.

Watching Hitchcock for science

Volunteers watched an eight-minute cut of the Hitchcock film and tapped an on-screen button whenever a meaningful unit ended and a new one began. That simple number – how many boundaries each person perceived – was the key measure.

Separately, participants reported the diversity of their recent social interactions (who they met and how they met them) and the complexity of their recent spatial routines (rooms and places visited, local exploration).

Only the social side consistently predicted finer segmentation. In statistical terms, total experiential diversity correlated with boundary frequency. Social diversity – not spatial diversity – accounted for unique variance when both were considered together.

Social life make the difference

The study found that people who had more assorted experiences identified more event boundaries, and their brains were able to consume this and know when one event started and ended.

“This suggests that living a fuller and more varied social life trains our brains to pick up more information around us, and helps to collate the information in a quicker, more digestible way,” said lead author Carl Hodgetts from the Department of Psychology at Royal Holloway.

“It’s not just about traveling to different places, or taking a different route to work each day, but connecting with a wide range of people, which helps us to understand what is happening in our world.”

This pattern fits a broader picture. Social contexts are complex and fast-changing, so frequent engagement may tune the brain to notice meaningful shifts.

These shifts include who’s present, what they intend, and how they feel – and the brain may catch them more quickly and more often.

The team also found that the link between social variety and segmentation was stronger in participants with higher trait anxiety. This suggests that heightened sensitivity to social-emotional cues can amplify the effect.

From memory to well-being

Event segmentation is not just a lab curiosity. It supports how we form episodic memories, plan actions, and move through spaces and social situations.

Finer segmentation has been tied to better recall and navigation in past work, and the new results imply that broader, more varied lives could sharpen those abilities by training the brain’s internal “film editor.”

Crucially, the association remained when the researchers controlled for loneliness and anxiety, indicating that the objective diversity of one’s experiences – not simply how one feels – relates to how the brain parses ongoing activity.

Social cues under the microscope

The study relied on self-reports of recent experience and on boundary counts during a single film. It cannot prove causation. Still, the results provide a baseline and a direction for future work.

The team plans to use MRI to test whether brain activity at event boundaries differs depending on the variety of people’s social life.

They also aim to drill down into which cues – social, spatial, or emotional – most strongly trigger boundaries.

The timing is also relevant. The work took place as UK COVID-19 restrictions eased.

This unusual mix of lingering limits and sudden rebounds in daily variety may have sharpened contrasts across participants. Replication across broader contexts will help establish how general the effect is.

A practical takeaway

You can’t watch Hitchcock all day, but you can widen your social world. The study points to a simple idea with broad appeal.

More assorted social experiences may help your brain detect the meaningful beats of life as they happen, making the stream of experience easier to digest and remember.

And that may matter as much for everyday functioning as for the science of how minds make sense of busy days.

The study is published in the journal iScience.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–