Human footprints, parallel tracks, and a 22,000-year-old mystery

At White Sands National Park in New Mexico, drag marks beside human footprints suggest people dragged loads with sled tools called “travois” about 22,000 years ago.

The work was led by Matthew Bennett, a geologist at Bournemouth University in the United Kingdom.

His research focuses on ancient footprints and how they record human movement, from individual steps to wider travel patterns.

White Sands sits on the dried floor of Paleolake Otero, where ancient mud preserved footprints from mammoths, ground sloths, camels, and early people.

Those trackways cover an Ice Age ecosystem in motion, tracing herds and hunters around the shrinking lake.

Radiocarbon and sediment evidence place the human footprints in the Last Glacial Maximum, the coldest stage of the Ice Age.

That timing means people were walking here while continental ice sheets were near their peak extent across the northern continent.

Reading the drag marks in detail

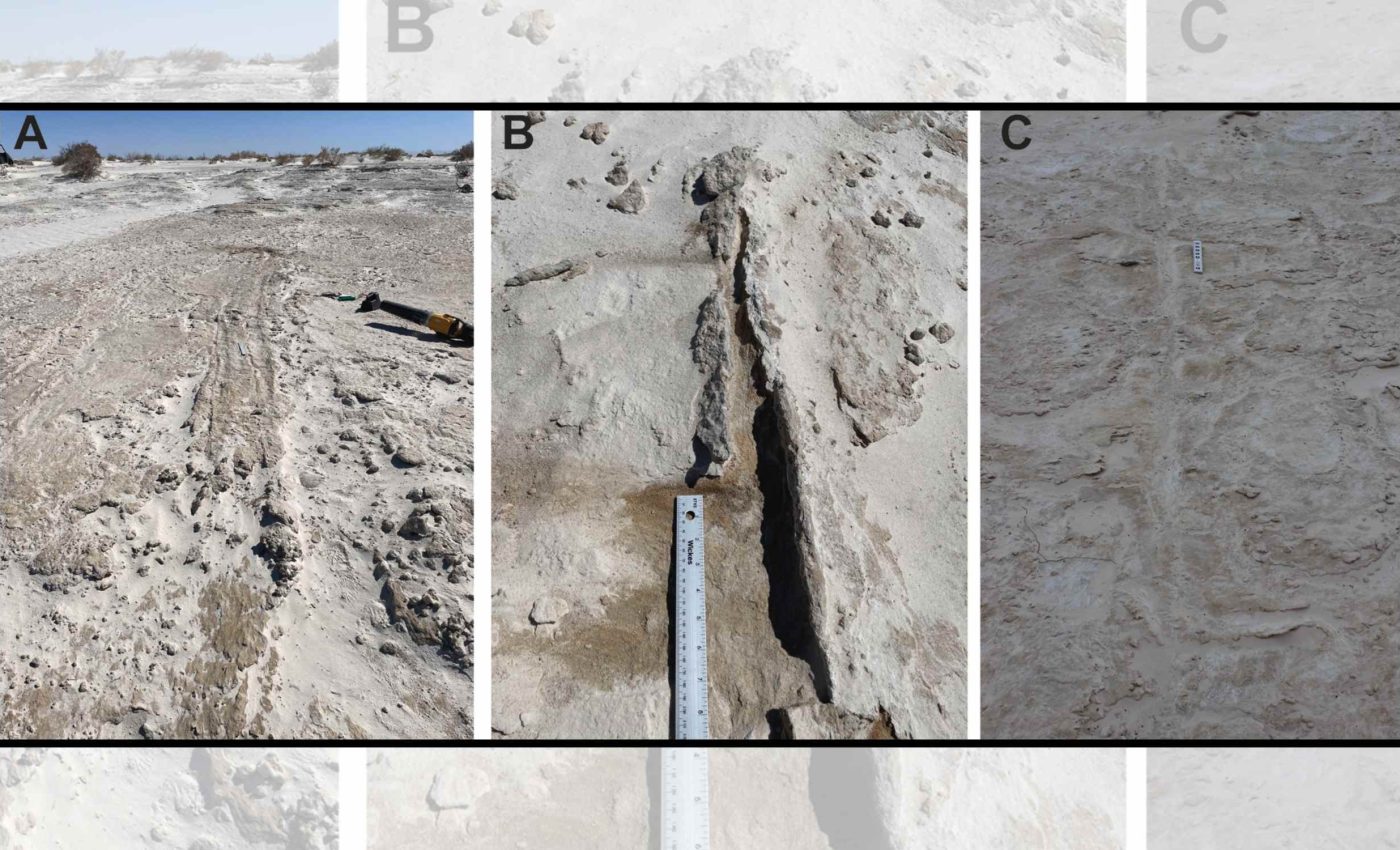

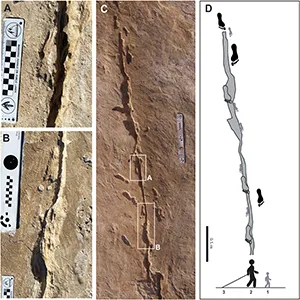

The new work zooms in on faint straight and curving grooves that run beside, across, and between the human footprints.

Travois are simple wooden frames dragged across the ground to carry loads. This new analysis points to these rudimentary devices as the source of those drag marks.

By mapping their shapes, depth, and spacing in three dimensions, the team created an ichnology for these lines.

Some grooves are narrow and deep, some broad and shallow, and others appear as twin parallel tracks that keep a steady distance apart.

In cross section, several cut into underlying layers and shove sediment to sides, evidence that something heavy scraped along rather than a light twig.

After comparing many options, from dragged branches to boat keels, the researchers argue that human made travois best match the evidence.

“We conclude that the most parsimonious explanation is that they represent drag marks” wrote Bennett. To check that idea, the team built simple travois replicas and pulled them across sticky mudflats in Britain and in Maine.

The modern tracks, with their paired grooves and overlapping footprints, closely matched what they saw in the ancient surfaces at White Sands.

Families on the move across the basin

Grooves rarely appear alone; there are footprints of different sizes walking beside them, crossing them, or even stamped right into the channels.

Some tracks are tiny, likely made by children, while others are larger, showing that mixed age groups were present during these journeys.

Such scenes suggest people were not just wandering, they were moving supplies, equipment, and probably loved ones together across the wetland.

Dragging loads on travois would have freed hands for tools or weapons and made longer trips more manageable on soft ground.

During these ancient visits, the basin held shallow lakes, marshes, and grasses that supported large Ice Age herds such as mammoths and camels.

That mix of water, vegetation, and roaming megafauna, large extinct animals like mammoths and giant sloths, favored groups who could move heavier loads.

Dating footprints and travois tracks

Working out how old these activities are depends on dating the sediments around the tracks rather than the footprints themselves.

Those first ages relied on seeds of the aquatic plant Ruppia cirrhosa, a method some researchers questioned, so others sought independent evidence.

Follow up work dated pollen grains and tiny quartz crystals from the same layers, strengthening the original age estimates for the trackways.

That included optically stimulated luminescence, a technique that measures when grains were last exposed to light, confirming an Ice Age era for these footprints.

Not everyone agrees on every detail, and some researchers still argue for younger ages at certain spots in the basin.

Even with those debates, the footprint ages cluster in a window that points to humans in North America earlier than classic migration models.

For the travois marks, those ages mean people were not only surviving but also organizing transport systems while ice and megafauna dominated the region.

That combination of age and behavior places their ingenuity deep inside the last Ice Age, not just at its melting edge.

Lessons from travois drag marks

Using travois meant people could move more things per trip, from firewood and food to stone tools or infants, without inventing wheels.

Simple wooden poles tied together can turn a walk into a planned haul, showing attention to future needs, not just immediate hunger.

Organizing those efforts likely required decisions about who pulled, who walked free of loads, and who watched for danger or openings in the terrain.

That kind of coordination, even with very basic gear, fits with a picture of communities sharing knowledge about routes, seasons, and resources.

For these groups, a travois probably doubled as general purpose gear that could become firewood, a frame for shelter, or support for carrying meat.

Archaeologists describe such tools as expedient technology, equipment made quickly from nearby materials and reused in many ways.

Similar grooves may sit unnoticed at other prehistoric sites, especially wherever ancient mudflats or lakebeds have preserved tracks of people and animals.

White Sands findings encourage scientists to examine subtle lines in excavation photos and new surveys, not only the footprints that first catch the eye.

The study is published in Quaternary Science Advances.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–