Covid aged our brains, even if you weren't infected - here's how it happened

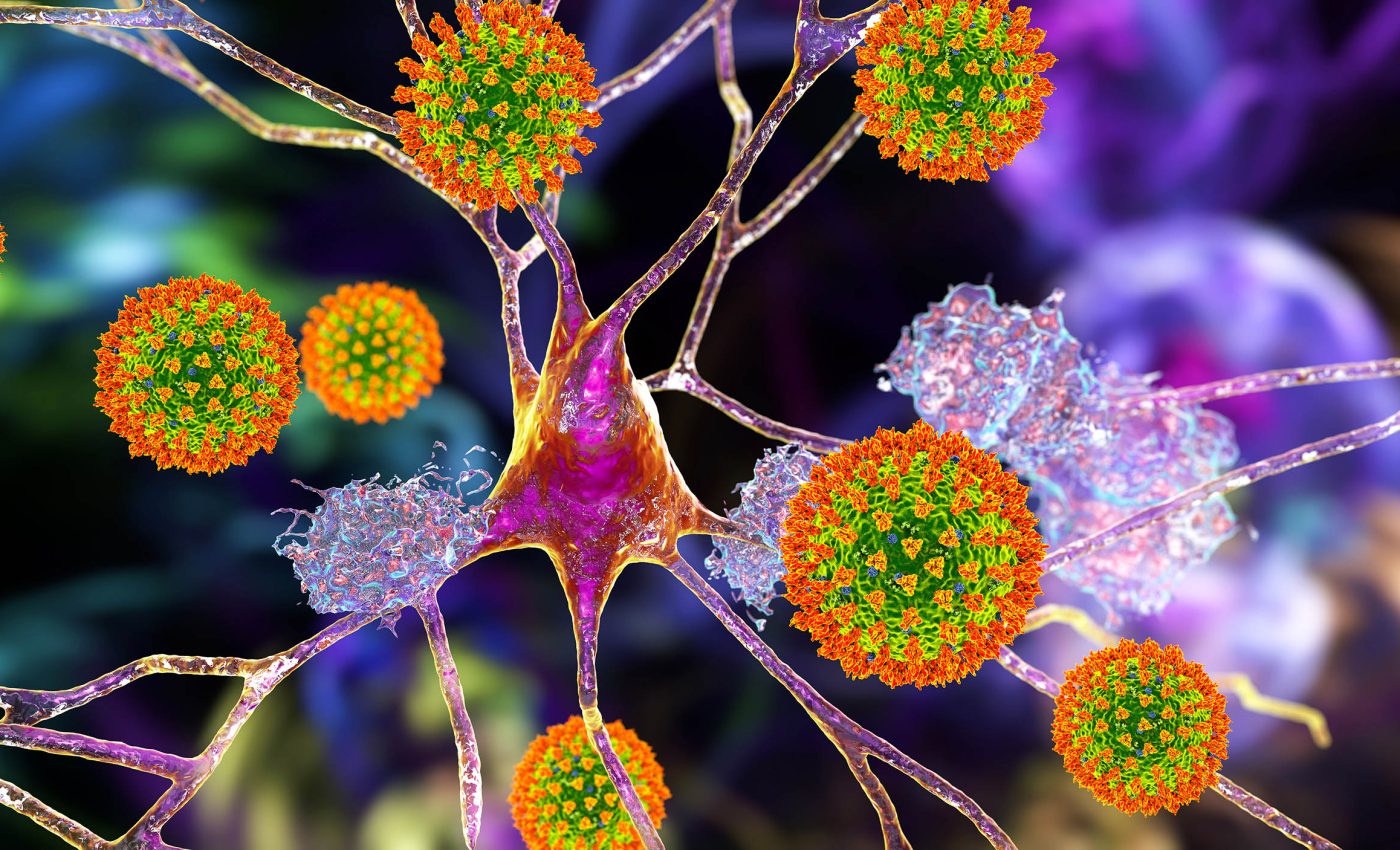

Scientists watched the pandemic reshape hospitals, jobs, and politics, but a new set of brain scans hints that it also reshaped the organ inside our skulls.

People who were never infected with SARS-CoV-2 showed brains that looked a few months older than expected.

This suggests that merely living through lockdowns, uncertainty, and social upheaval left a subtle neurological signature.

The findings come from a new investigation by Dr. Ali-Reza Mohammadi-Nejad of the University of Nottingham’s School of Medicine.

Pandemic stress aged the brain

Nearly 1,000 healthy adults enrolled in the UK Biobank underwent two MRI sessions – one before March 2020. For half of them, a second scan took place between 2021 and 2023.

Researchers used machine learning models built from 15,334 pre-pandemic scans to estimate each volunteer’s brain age gap, the difference between predicted brain age and chronological age. A positive gap means the brain appears older on imaging, a negative gap younger.

“What surprised me most was that even people who hadn’t had Covid showed significant increases in brain aging rates,” said Mohammadi-Nejad.

Participants who weren’t infected but lived through the pandemic showed an average increase in brain age of about five and a half months compared to similar individuals who were scanned twice before 2020.

Older age, male sex, and lower income made the acceleration steeper, demonstrating that biology and biography travel together.

Stress accelerates brain aging

The study adds to a growing collection of research that links chronic stress hormones to faster structural decline in white matter.

Elevated allostatic load, the body’s cumulative stress score, correlates with brains that look a year or two older than they should.

Isolation compounds the problem. A study of 24,867 adults found loneliness and poverty were linked to higher brain age and worse physical health. Lockdowns amplified both stress and isolation, so a slight pandemic era uptick in brain age is biologically plausible.

Animal studies support the idea. Rodents under constant stress show brain inflammation and damage in areas used to estimate brain age.

Infected brains show more decline

Covid-19 infection had its own costs. Participants who caught the virus took longer on the Trail Making Test (TMT), a timed task of mental flexibility, than both controls and pandemic peers who were never infected with the virus.

A separate Japanese cohort study confirms that slower trail making times flag early cognitive change in older adults.

Brain scans of infected people elsewhere echo the pattern. A 2022 report comparing 401 infected volunteers with 384 controls found greater gray matter loss in orbitofrontal and parahippocampal regions, areas tied to smell and memory.

In the Nottingham analysis, only the infected subgroup linked larger brain age jumps with worse trail making scores, hinting that viral effects and stress effects overlap but are not identical.

Stress hits the vulnerable harder

Living in a disadvantaged neighborhood, working an unstable job, or lacking higher education magnified the brain aging-signal.

Employment insecurity, for example, added almost six extra months to the gap compared with securely employed peers.

These scans make visible a truth social scientists have charted for decades: financial strain and limited social capital seep into physiology. When economic cushions thinned during lockdowns, the impact may have sped up.

The data support protecting vulnerable groups during crises, as stress leaves measurable effects on the brain.

Healing depends on lifestyle

“We can’t yet test whether the changes we saw will reverse, but it’s certainly possible, and that’s an encouraging thought,” said Professor Dorothee Auer, senior author of the study.

Brain age models capture averages, not destinies. Earlier studies of stress recovery suggest that gray matter volume and brain connectivity can rebound when stress is reduced. Recovery is more likely when lifestyle factors like sleep, exercise, and social contact improve.

Longer follow-ups will reveal whether the pandemic’s neural footprint fades, stays put, or predicts later cognitive trouble.

For now, the scans remind us that global emergencies do not end at the ICU door – they echo inside healthy brains, too, in ways only careful imaging can catch.

Brain scans reveal policy impact

The study adds weight to the idea that brain age could become a routine marker in population health.

If small changes in daily life – or major global events – show up clearly on brain scans, public health leaders might one day use brain age metrics to evaluate policy impacts over time.

The research also raises the question of how resilience works at a neural level. Some people weathered the pandemic with little psychological or neurological wear, while others showed sharper declines.

Understanding what protects brain health under chronic stress could shape future treatments or community interventions.

The study is published in the journal Nature Communications.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–