USS New Orleans bow found 83 years after it was sunk by a torpedo in World War II

Eighty‑three years after a torpedo tore it away, the 150‑foot steel bow of USS New Orleans reappeared, this time as pixels on sonar and video, sitting about 2,215 feet down in the Solomon Islands’ Iron Bottom Sound.

The heavy cruiser lost nearly one‑third of her hull and 182 sailors during the November 1942 Battle of Tassafaronga, yet damage‑control teams braced the jagged wound with coconut logs and steered the ship home in reverse to Puget Sound for repairs.

A bow lost for eight decades

“This imagery was viewed in real time by hundreds of experts around the world, who all worked together to make a positive identification of the findings. The discovery highlights the power of having multiple scientists and technologies work together to achieve a common goal,” said Daniel Wagner, chief scientist with Ocean Exploration Trust.

“By all rights, this ship should have sunk,” retired Rear Admiral Samuel J. Cox. Japanese “Long Lance” torpedoes struck after midnight, detonating forward magazines and shearing off turrets one and two.

With steering gone and compartments flooding, electricians jury‑rigged power, sailors shoved timber through shattered frames, and the crippled vessel crawled into Tulagi Harbor before the makeshift bow fell apart.

USS New Orleans wreck site

Five night battles raged here between August and December 1942, claiming 20,000 lives, 111 naval vessels, and 1,450 aircraft from Allied and Japanese forces.

Most wrecks rest inside a corridor only 25 nautical miles wide, turning the sound into a condensed graveyard of steel and sacrifice.

So far just 30 of those wartime hulks have been located, leaving dozens more for future surveys and the families who still wait for closure.

How robots share the workload

Discovery began with USV DriX, a 25‑foot uncrewed surface vessel developed by Exail and operated by the University of New Hampshire.

Running pre‑programmed lawn‑mower lines, DriX beamed high‑resolution seafloor mosaics back to E/V Nautilus, where pilots dispatched Hercules, a tethered remote‑operated vehicle, to inspect an intriguing 150‑foot shadow the sonar had painted.

“NOAA Ocean Exploration’s mission is to explore the ocean for America’s benefit,” said Captain William Mowitt, acting director of NOAA Ocean Exploration, adding that pairing DriX with deep‑diving ROVs “has the potential to reshape our understanding of what lies in the deep ocean.”

Inside the drix toolbox

A carbon‑Kevlar composite hull lets the craft slice waves at 13 knots while weighing only 1.4 tons, light enough for a single point lift.

Seven‑day endurance at 7 knots means the boat can map while the crew sleeps, delivering coverage impossible for a conventional ship and burning a fraction of the fuel.

Twin EM‑712 and EM‑2040 multibeam sonar units sweep frequencies from 40 kHz to 400 kHz, detailing contours from tidal flats out to 1,600 feet, while an EK‑80 fisheries echosounder tracks mid‑water life that often crowds wreck sites.

Real‑time kinematic GPS, lidar, and long‑range marine broadband radios stitch the surface plot to ROV video, so historians can consult, annotate, and archive images as they stream ashore.

The team’s approach, pairing autonomous surface vessels like DriX with real-time feedback from ROVs, could be applied to other unexplored maritime graveyards around the world.

From the Arctic to the Coral Triangle, wreck sites hold historical and ecological significance that often go unstudied because of depth, cost, or geopolitical sensitivity.

Honoring USS New Orleans crew

Cox called the find “an opportunity to remember the sacrifice of this valiant crew, even on one of the worst nights in U.S. Navy history,” underscoring that exploration is as much about people as hardware.

Telepresence let descendants in Louisiana, naval architects in Japan, and students in Australia witness the anchor still stamped “Navy Yard” on live video, knitting a dispersed community around a single rusted artifact.

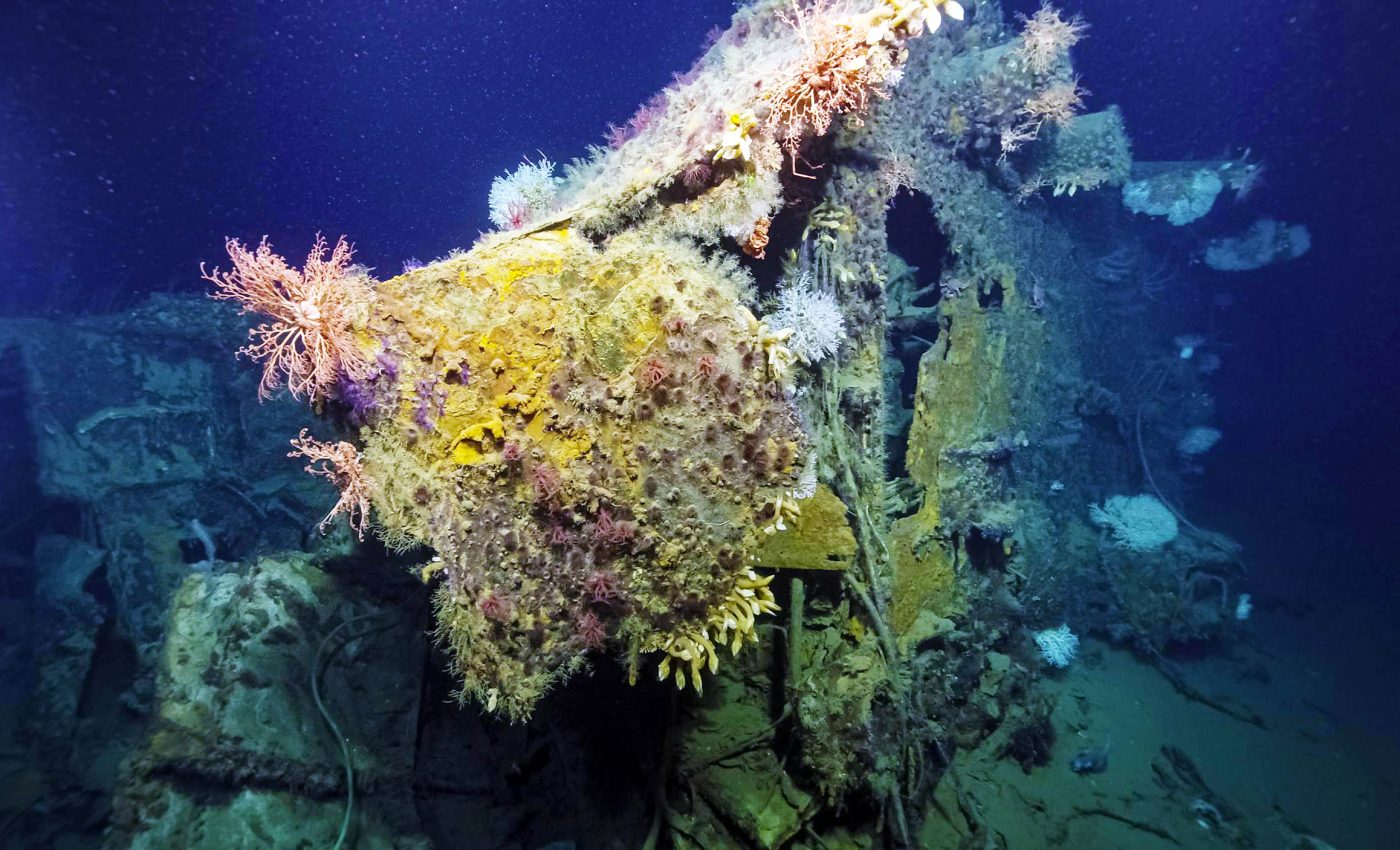

Archaeologists photographed but did not disturb the site, treating it as a war grave and deep‑sea reef now colonized by corals, anemones, and basket stars.

More wrecks near USS New Orleans

DriX will continue to grid the 1,400‑foot‑deep basins of Iron Bottom Sound through mid‑July, queuing new ROV dives for wrecks long rumored but never confirmed.

Each stitched mosaic whittles down the unknown, proving that small autonomous craft and human curiosity can retrieve lost chapters of history, one sonar ping at a time.

Why these finds still matter

Shipwrecks like USS New Orleans serve as underwater time capsules that link global history with modern identity. They’re not just remnants of war, they’re markers of engineering, courage, and diplomacy that shaped the present.

Their rediscovery helps nations reconcile with shared pasts, especially in regions like the South Pacific where legacy and loss are deeply intertwined.

These missions renew collective memory and allow younger generations to engage with stories often left out of textbooks.

Click here to see more images of this historic discovery of the USS New Orleans.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–