Krasheninnikova erupts after 475 years of silence

For the first time in centuries, a quiet giant on Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula has stirred back to life. The Krasheninnikova volcano, a mountain long written off as dormant, surprised observers when it began to erupt on August 3, 2025.

Lava streamed down, ash rose into the air, and thick plumes of volcanic gases rose over the mountain. After more than 400 years of silence, this sudden shift caught many people off guard.

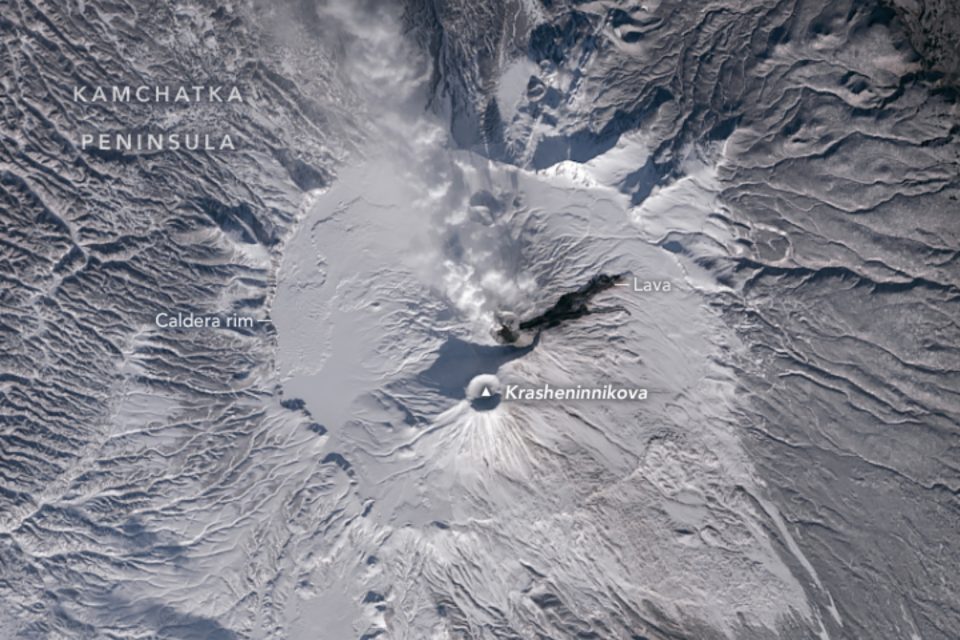

The activity has continued for several months. On November 14, the OLI-2 instrument on Landsat 9 captured a clear image of the current eruption.

In the image, a volcanic plume can be seen rising from one of the volcano’s craters and drifting toward the northwest. It stands out against the white snow that covers the surrounding slopes.

A sleeping volcano wakes up

Krasheninnikova is an unusual feature on the landscape – made up of two overlapping stratovolcanoes inside a caldera that spans about six miles across. That depression formed roughly 30,000 years ago during a major eruption.

The last known event before today’s activity happened around the year 1550. In that earlier episode, lava spilled out from both summit cones.

This year’s eruption started five days after a magnitude 8.8 earthquake struck the southern end of the peninsula. The epicenter was about 150 miles from the volcano. The quake was one of the strongest measured by modern seismic instruments.

Scientists have long discussed whether major earthquakes can trigger eruptions, and some think that in certain cases these events can push an already primed volcano over the edge.

A team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory has been studying the connection. They used interferometric synthetic aperture radar, or InSAR, to map how the ground moved after the quake.

The method works by comparing radar signals taken from satellites at different times. Even small changes in the surface can be spotted with this approach. It’s a tool that helps scientists study earthquakes, landslides, and volcanic unrest.

Detecting changes beneath the surface

In this case, InSAR detected surface deformation at Krasheninnikova shortly after the quake but before the eruption began. That shift hinted at something moving underground. The data pointed to a dike of magma pushing upward.

This caught the attention of Paul Lundgren, a geophysicist at JPL who is now analyzing the movement of magma beneath the volcano.

“In keeping with a volcano that had not erupted or shown any signs of activity in about 400 years, I would consider this eruption as triggered by the magnitude 8.8 earthquake,” noted Lundgren.

The idea fits with what volcanologists know about how magma behaves. A large earthquake can change stress patterns in the surrounding crust. If magma is already pressurized and close to the surface, that extra nudge can help it rise.

An earthquake cannot create magma from nothing, but it can influence a system that’s nearing a tipping point.

The ongoing activity offers a rare look at a volcano coming back online after centuries of rest. It gives scientists a chance to understand how magma moves through long-dormant systems and what might set them off.

A busy neighborhood of volcanoes

Even without a major earthquake, it’s common for several volcanoes in Kamchatka to erupt at the same time.

The peninsula sits above a subduction zone where one tectonic plate dives beneath another, creating ideal conditions for repeated volcanism. Ash clouds and lava flows are nothing new here.

One of Krasheninnikova’s closest neighbors, Kronotskaya Sopka – also known as Kronotsky – erupted briefly on October 4, marking its first activity in 102 years.

The explosive event blasted an ash plume nine kilometers above sea level, according to reports from the Kamchatkan Volcanic Eruption Response Team.

The wider history of the mountain includes large eruptions during the late Pleistocene and early Holocene that sent out massive lava flows. Those flows eventually dammed a river and formed Lake Kronotskoye, now the largest lake in the region.

Krasheninnikova’s latest eruption is far smaller than those dramatic ancient events, but it still carries weight.

Long-quiet volcanoes attract attention because they remind everyone that geologic time moves at its own pace. A volcano that appears still for centuries can surge with only a hint of warning.

Image Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–