Capuchin monkeys have developed a very disturbing 'social tradition' of abducting babies

Not all traditions make sense. That’s true for humans, and maybe even monkeys, as we are about to learn. We humans are experts at passing down habits, rituals, and cultural quirks that don’t always have a clear purpose.

Why do we knock on wood or toss salt over our shoulder? Half the time, we’re just copying what we’ve seen others do.

Scientists have long wondered: do animals do this too? Can they pass along behaviors that seem… well, pointless?

Turns out, maybe they can.

Capuchin monkeys and baby howlers

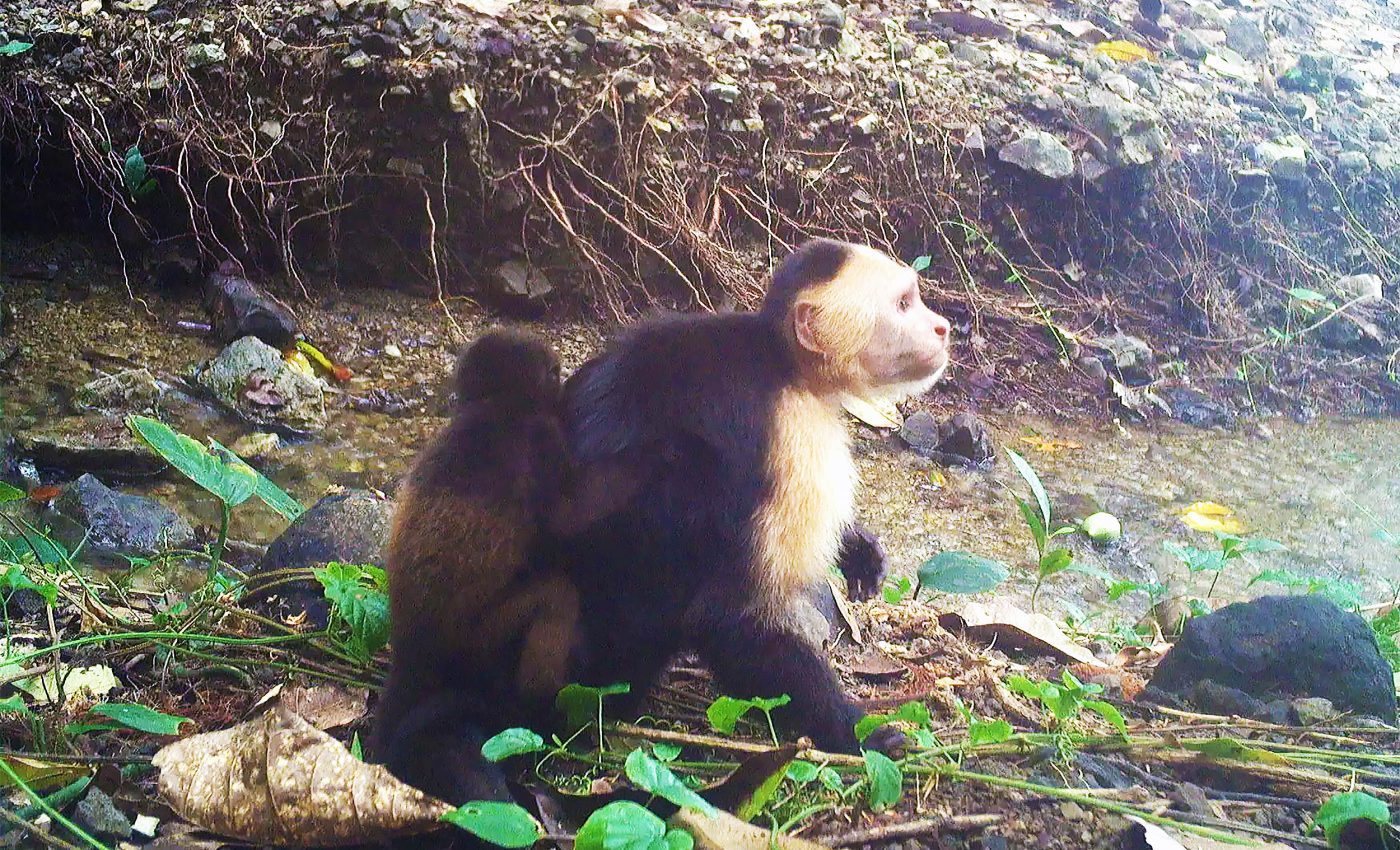

On a remote island in Panama, researchers spent over a year watching a group of young male capuchin monkeys do something bizarre: they started grabbing and carrying around baby howler monkeys from another species.

This wasn’t a one-off event – it happened again and again, involving five different capuchins from the same group. Even more fascinating, these are the same monkeys known for a rare tradition of using stone tools.

The scientists tracked how this odd “howler abduction” behavior began with one curious monkey and slowly caught on with others.

And here’s the kicker: this trend, strange as it seems, may have spread the same way their more practical tool-use habits did – through social learning, imitation, and the powerful pull of monkey see, monkey do.

Studying capuchin baby abduction

Researchers from the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior (MPI-AB) and other institutions began monitoring these capuchins in Coiba National Park back in 2017.

Their camera traps were designed to capture the tool-using behaviors of the primates. But in 2022, something unexpected showed up in the footage.

“It was so weird that I went straight to my advisor’s office to ask him what it was,” remembered Zoë Goldsborough, who is conducting her dissertation at MPI-AB.

What she saw was a capuchin carrying an infant howler monkey. Nothing like it had appeared before in five years of data. Curious and concerned, the researchers decided to dig deeper.

First observation of unusual behavior

Goldsborough began reviewing the footage from every motion-triggered camera on the island. She found more than just a single instance.

There were actually four different howler infants being carried. And in most of the clips, the carrier was the same capuchin: a young male they nicknamed “Joker.”

This raised new questions. How did Joker get the babies? And why was he carrying them?

“At first, we thought it could be adoption,” said Goldsborough.

Cross-species adoption

There are rare stories of animals adopting babies of other species. In one famous case, a pair of capuchins adopted a marmoset and raised it to adulthood.

But there was a catch. Adoption is typically done by females, often as a way to practice mothering. This made Joker’s behavior especially unusual.

“The fact that a male was the exclusive carrier of these babies was an important piece of the puzzle,” she adds.

For a while, nothing else surfaced. The team assumed it was an isolated case. Capuchins are known for trying new things, so one monkey acting oddly wasn’t too surprising.

“We’d decided that it was one individual trying something new,” said Brendan Barrett, a group leader at MPI-AB.

Other capuchins start stealing babies

Five months later, the researchers hit pay dirt. The cameras captured more footage of howler infants being carried – this time by multiple monkeys. The infants were verified as separate individuals by a howler monkey expert from Ithaca College.

And now Joker had company. Four other young male capuchins were also carrying howler babies.

In a span of just 15 months, five capuchins carried a total of 11 howler infants. Each baby clung to the back or belly of its carrier.

The monkeys didn’t change their daily routines. They kept traveling and using tools, even with a baby howler in tow.

“The complete timeline tells us a fascinating story of one individual who started a random behavior, which was taken up with increasing speed by other young males,” said Barrett.

The team documented the entire timeline on an interactive website. What emerged was a new kind of social tradition – what the researchers described as a cultural fad.

Like whales wearing salmon hats or chimpanzees sticking blades of grass in their ears, the capuchins appeared to be mimicking one another.

Sad side of animal research

But unlike other animal fads, this one had troubling consequences. The howler infants were very young – less than four weeks old.

Their parents were seen nearby, calling to them from the trees. Four of the babies died. The researchers believe none of them survived.

“The capuchins didn’t hurt the babies,” stressed Goldsborough, “but they couldn’t provide the milk that infants need to survive.”

So what did the capuchins get out of it? Nothing obvious. They didn’t eat the infants, interact with them playfully, or receive any extra attention from others in their group.

“We don’t see any clear benefit to the capuchins,” said Goldsborough, “but we also don’t see any clear costs, although it might make tool use a little trickier.”

What does all of this mean?

This may be the first recorded case of a social tradition where animals repeatedly abduct and carry the young of another species – without any benefit to themselves.

It also shows that culture in animals isn’t always functional or harmless.

“We show that non-human animals also have the capacity to evolve cultural traditions without clear functions but with destructive outcomes for the world around them,” commented Barrett.

This opens up a deeper question.

“The more interesting question is not ‘why did this tradition arise?’ but rather ‘why here?’”

Do capuchins innovate out of boredom?

These same capuchins are also the only ones known to use stone tools on Jicarón Island. They crack nuts and shellfish with stones. And just like the howler-carrying behavior, this tool use is performed only by males.

Why these traditions? Why only males?

“Survival appears easy on Jicarón. There are no predators and few competitors, which gives capuchins lots of time and little to do,” said Meg Crofoot, managing director at MPI-AB.

“It seems this ‘luxurious’ life set the scene for these social animals to be innovators. This new tradition shows us that necessity need not be the mother of invention. For a highly intelligent monkey living in a safe, perhaps even under-stimulating environment, boredom and free time might be sufficient.”

Potential impact on howler monkeys

The camera trapping period ended in July 2023. It’s still unclear if the behavior is continuing. If it spreads or begins to impact the local howler monkey population, which is an endangered species, it could become a serious conservation issue.

“Witnessing the spread of this behavior had a profound effect on all of us,” said Crofoot.

“We therefore feel even more responsible to keep learning from this natural population of primates who, to our knowledge, are the only ones on earth to be practicing this strange tradition.”

The story unfolding on Jicarón Island is a reminder that animals, like humans, can be deeply influenced by their peers.

Sometimes, those influences lead to remarkable adaptations. Other times, they can lead to something far more puzzling.

The full study was published in the journal Current Biology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–